by Debbie Burke

Most people are familiar with “fight or flight” response to a threat. Physiologist and Harvard Medical School chair, Walter Bradford Cannon isolated those two reactions in the 1920s after observing animals in the lab. When animals were frightened or under stress, they displayed behaviors that evolution had programmed into them millions of years before for survival. Faced with a threat, animals either stood their ground and fought the attacker or ran away from it.

Most people are familiar with “fight or flight” response to a threat. Physiologist and Harvard Medical School chair, Walter Bradford Cannon isolated those two reactions in the 1920s after observing animals in the lab. When animals were frightened or under stress, they displayed behaviors that evolution had programmed into them millions of years before for survival. Faced with a threat, animals either stood their ground and fought the attacker or ran away from it.

Photo credit: Bernard Dupont CC by SA 2.0

Our human ancestors developed the same programming. They either grabbed a big stick to fight off the lion or they ran like hell to escape it.

These physiological reactions are involuntary, triggered by the autonomic nervous system. Signs include dilated pupils, heightened hearing, racing heart, rapid breathing, and tense muscles to prepare the body to fight or run away.

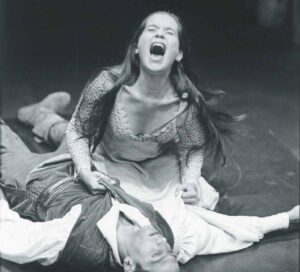

“Freeze” is a third possible reaction to threats and wasn’t widely recognized untill the 1970s. Its evolutionary purpose may have been to avoid attracting the attention of a predator. If the prey didn’t move, the predator would hopefully not notice it and walk on by.

Public domain photo

I’ve watched young fawns remain completely still to blend in with cover. However, when deer freeze in the headlights of your speeding car, that option often doesn’t work out well for survival.

Recently I learned about a fourth reaction: fawn. The term was coined by psychotherapist Pete Walker in 2003 to describe behavior intended to appease the threat and avoid being harmed.

Photo credit: Andrew Lorenz CC by SA 3.0

For instance, dogs may roll on their backs and display their bellies to acknowledge the dominance of another dog. Crouching and cowering are also signs of fawning.

This reaction is often seen in human abuse victims who try to please or show subservience to a potential attacker to deflect violence. They also may agree with the threatening person, hoping to head off an argument that could lead to possible abuse.

This article by Olivia Guy-Evans describes physical responses that occur in the body during fight, flight, freeze, or fawn.

While fight, flight, and freeze are instinctual, fawn is a learned behavior, according to Shreya Mandal JD, LCSW, NBCFCH. When faced with chronic stress and threat, some people develop the fawn reaction to survive.

In a June 2025 article in Psychology Today, she writes:

“Rooted in complex trauma, the fawn response emerges when a person internalizes that safety, love, or even survival depends on appeasing others, especially those who hold power over them. It is a profound psychological adaptation, often shaped in childhood, in homes where love was conditional, inconsistent, or entangled with emotional or physical threat.

“For many survivors, especially those from marginalized communities, fawning becomes a deeply embodied pattern. As a trauma therapist and legal advocate, I’ve witnessed this adaptive strategy in clients across many settings: survivors of interpersonal violence, those navigating carceral systems, immigrants shaped by colonial legacies, employees navigating toxic work environments, and children of emotionally immature parents. The fawn is the child who learns to become invisible or overly helpful to avoid punishment. It’s the adult who minimizes their needs in relationships. It’s the employee who fears negative consequences and retaliation. It’s the incarcerated woman who apologizes before speaking her truth in court.”

The person may not consciously be aware of what they are doing. They simply understand they will “stay safe by pleasing the powerful.”

As crime writers, we often put our characters in conflict with others. When you write these scenes, try viewing them through the lens of what Pete Walker calls the “four Fs.”

Do they fight the threat?

Do they flee?

Do they freeze in their tracks?

Do they fawn to appease the attacker?

Their reactions depend on their individual personalities and psychological makeup. Often their behavior is shaped by childhood trauma that conditioned their responses to conflict.

If you’re not sure how your character would react to peril, try writing short sample scenes. In the first example, have them fight. In the second, they flee. In the third, they freeze. In the fourth, they fawn. Which of the four scenes seems the most authentic for your character’s personality and background?

Another prompt to develop your character is to put them in a risky situation and free-write what they do. They may surprise you by reacting in a way you didn’t expect. A character you thought was timid may stand their ground and put up a ferocious fight. A blustering, aggressive character may freeze or fawn when faced with actual danger.

When a character surprises you, dig deeper into the reasons behind their action. Were they the only defense between their younger sibling and an abusive parent? Were they punished without reason or treated unjustly? Did they resolve to never be put in a submissive position again?

Short writing prompts like these help you get to know your character and learn how they react under stress. Their background may not be shown in the story but you, as the author, will better understand how to portray them in an authentic, realistic way.

~~~

TKZers: When confronted with danger, does your main character fight, flee, freeze, or fawn?

~~~

Debbie Burke’s new book The Villain’s Journey-How to Create Villains Readers Love to Hate is now for sale in hardcover, as well as ebook and paperback.

Every character is the hero of their own story. Even the villain.

Every character is the hero of their own story. Even the villain.

Characters need personal growth to achieve their goals. If the character seeks to improve themselves in some way — at work, in relationships, or spiritually — or defeat the villain, their fatal flaw will often sabotage early efforts.

Characters need personal growth to achieve their goals. If the character seeks to improve themselves in some way — at work, in relationships, or spiritually — or defeat the villain, their fatal flaw will often sabotage early efforts.