How do characters come to you? For me, each book can be different. I don’t have a set method, nor do I want to nail my process down. I’ve awakened in the middle of the night with a character speaking to me about his or her story. I leap from bed and rush to the bathroom with pen and paper in hand to jot down notes.

Sometimes from my preliminary research, I can meld 2-3 ideas together and a character might spring from that work. For example, I might realize I need an adventurer hero, a love interest and one of them might need a scientific background or have other special cognitive skills to pull off the plot that’s developing. Those characters come at me slowly and build, where I sometimes throw in fun hobbies or weirdness to keep the plot interesting.

Have you ever gone back into a novel you’ve already written and examined character archetypes?

You can also do this deep dive for themes you generally write about, even if it’s not a conscious awareness you have when you first start your project. I write from a gut level. Too much structure might inhibit my process, but I do find it interesting to take a closer look after I finish writing a book, especially if it sells well and the feedback is good from industry professionals. It’s helpful to dig into a plot I created organically to find threads of themes I love to explore.

Let’s take a closer look at character archetypes. In researching this post, I found a more comprehensive list of 99 Archetypes & Stock Characters that Screen Writers Can Mold that screenwriters might utilize in their craft. Archetypes are broader as a foundation to build on. Experienced editors and industry professionals can hear your book pitch and see the archetypes in their mind’s eye. From years of experience, it helps them see how your project might fit in their line or on a book shelf.

But to simplify this post and give it focus, I’ll narrow these character types down to Swiss Psychiatrist Carl Jung‘s 12-Archetypes. Listed below, Jung developed his 12-archetypes, as well as their potential goals and what they might fear. Goals and fears can be expanded, but think of this as a springboard to trigger ideas.

TYPE/GOAL/FEAR

1.) Innocent

GOAL – Happiness

FEAR – Punishment

2.) Orphan

GOAL – Belonging

FEAR – Exclusion

3.) Hero

GOAL – Change World

FEAR – Weakness

4.) Caregiver

GOAL – Help Others

FEAR – Selfishness

5.) Explorer

GOAL – Freedom

FEAR – Entrapment

6.) Rebel

GOAL – Revolution

FEAR – No Power

7.) Lover

GOAL – Connection

FEAR – Isolation

8.) Creator

GOAL – Realize Vision

FEAR – Mediocrity

9.) Jester

GOAL – Levity & Fun

FEAR – Boredom

10.) Sage

GOAL – Knowledge

FEAR – Deception

11.) Magician

GOAL – Alter Reality

FEAR – Unintended Results

12.) Ruler

GOAL – Prosperity

FEAR – Overthrown

I recently sold a series to The Wild Rose Press. Book 1 is called THE CURSE SHE WORE – A Trinity LeDoux novel.

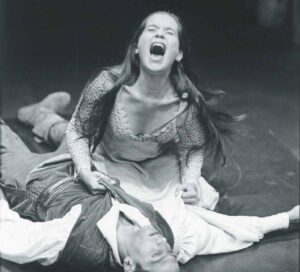

TRINITY – When I looked back at my heroine, Trinity appeared to be a combination of two archetypes, until I gave her a closer look. On the surface, she’s an innocent AND an orphan, but when I examined her from the GOAL and FEAR angles, I saw her clearly as an ORPHAN. No family. She’s homeless and living on the streets of New Orleans. She hasn’t known much happiness and punishment would only make her more stubborn. Her soft underbelly lies in her own thoughts on where she belongs and what she deserves. She keeps her life at a distance from others–her self-imposed exclusion. She thinks she doesn’t need anyone until she meets Hayden, but what she has planned for him, there won’t be anything left to build on. Loyalty can be a double-edged sword.

HAYDEN – My hero Hayden Quinn doesn’t fall neatly into the HERO category. Because of his psychic ability, he’s become a CAREGIVER to a small needy Santeria community in New Orleans. But his gift didn’t help him when he needed it most. He’s drawn to help others, but his ability only reminds him of the worst day of his life.

CROSSED PATHS – As a child of the streets, Trinity exploits Hayden’s guilt and grief to get what she wants. He’s unable to say no because of his guilt. For an author, it’s not easy to walk a line of conflict that I wanted to sustain throughout the first novel in this series. Surprises and unexpected outcomes twist through the plot until the very last page of book 1. The roots of their conflict grow deeper and extend into book 2.

SUMMARY: Whether you use these 12-archetypes to analyze a completed manuscript or consider them when you begin framing a new story, these building blocks can sustain an effective character study and get you thinking. It helped me dive deeper into my characters and this will help me develop the series. Any series needs the stakes to escalate and it all springs from a foundation of knowing your characters well. You have to keep punishing them. Show the reader why your characters deserve star status.

Can you see how you might utilize a list if archetypes to infuse your creative process?

When you consider these basic types, imagine pitting them against one another for sustained conflict. In the case of Trinity and Hayden, she risks putting his life at risk out of her loyalty to a dead friend. Any hope she had for a future is snuffed out by her own decisions.

For him, the very gift that had been a blessing failed him at the worst time of his life. Now his gift might kill him, but he can’t resist protecting Trinity. It’s in his nature.

All Hayden and Trinity have in common is death.

FOR DISCUSSION:

1.) As an exercise, forge conflict between two archetypes of your choosing to create a one-liner plot pitch.

2.) Share your main character archetype from your current or latest WIP. Does the Carl Jung matrix above help you define your character?

***