by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

If everything seems under your control, you’re not going fast enough. – Mario Andretti, legendary race car driver

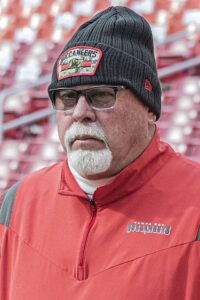

Bruce Arians

Recently we had a bit of a discussion on taking risks, as part of Terry’s post on rules for writers. Today I’d like to give risk more focused attention.

Remember back in 2021 when the Tampa Bay Buccaneers won the Super Bowl by destroying the favored Kansas City Chiefs, 31-9? With a 43-year-old quarterback named Brady. And the oldest coach ever to win the big game, 67-year-old Bruce Arians.

Arians had followed a long and rocky career path as a quarterbacks coach in the NFL. He got hired and fired several times. His first year as head coach for the Bucs the team went 7–9. Then along came Brady and the Super Bowl.

Through it all, Arians had a saying that kept him and his teams motivated. He actually got it from a guy at a bar at a time when Arians thought his dream of being a head coach would never be realized. That saying is: No risk it, no biscuit.

Now doesn’t that sound like a quintessential football coach axiom?

As Arians’ cornerback coach, Kevin Ross, explained it, “If you don’t take a chance, you ain’t winnin’. You can’t be scared.”

What might this mean for the writer?

Risk the Idea

I think each novel you write should present a new challenge. It might be a concept or “what if?” that will require you to do some fresh research. My new Mike Romeo thriller (currently in final revisions) revolves around a current issue that is horrific and heartbreaking. I could have avoided the subject altogether. But I needed to go there.

My next Romeo, in development, came from a news item about a current, but not widely reported, controversy. It’s fresh, but I’ve got a lot of learning to do. I’m reading right now, I’ll be talking to an expert or two, and soon will be making a location stop for further research.

I do this because I don’t want to write a book in the series where someone will say, “Same old, same old.”

Admittedly, writing about “hot-button” issues these days carries a degree of risk. Especially within the walls of the Forbidden City where increasingly the question “Will it sell?” is overridden by “Will it offend?”

But as the old saying goes, there is no sure formula for success, but there is one for failure—try to please everybody.

Craft Risk

Are you taking any risks with your craft? Are you following the Captain Kirk admonition to boldly go where you have never gone before?

There are 7 critical areas in fiction: plot, structure, characters, scenes, dialogue, voice, and meaning.

You can take one or all of these and determine to kick them up a notch. For example:

Plot—Have you pushed the stakes far enough? If things are bad for the Lead, how can you make them worse? I had a student in a workshop once who pitched his plot. It involved a man who was carrying guilt around because his brother died and he didn’t do enough to save him. I then asked the class to do an exercise: what is something your Lead character isn’t telling you? What does he or she want to hide?

I asked for some examples, and this fellow raised his hand. He said, “I didn’t expect this. But my character told me he was the one who killed his brother.”

A collective “Wow” went up from the group. But the man said, “But if I do that, I’m afraid my character won’t have any sympathy.”

I asked the group, “How many of you would now read this book?”

Every hand went up.

Take risks with your plot. Go where you haven’t gone before.

Characters—Press your characters to reveal more of themselves. I use a Voice Journal for this, a free-form document where the character talks to me, answers my questions, gets mad at me. I want to peel back the onion layers.

How about taking a risk with your bad guy? How? By sympathizing with him!

Hoo-boy, is that a risk. But you know what? The tangle of emotions you create in the reader will increase the intensity of the fictive dream. And that’s your goal! In the words of Mr. Dean Koontz:

The best villains are those that evoke pity and sometimes even genuine sympathy as well as terror. Think of the pathetic aspect of the Frankenstein monster. Think of the poor werewolf, hating what he becomes in the light of the full moon, but incapable of resisting the lycanthropic tides in his own cells.

Dialogue—Are you willing to make your dialogue work harder by not always being explicit? In other words, how can you make it reveal what’s going on underneath the surface of the scene without the characters spelling it out?

Voice—Are you taking any risks with your style? This is a tricky one. On the one hand, you want your story told in the cleanest way possible. You don’t want style larded on too heavily.

On the other hand, voice is an X factor that separates the cream from the milk. I’ve quoted John D. MacDonald on this many times—he wanted “unobtrusive poetry” in his prose.

I’m currently reading the Mike Hammer books in order. It’s fascinating to see Mickey Spillane growing as a writer. His blockbuster first novel, I, The Jury, is pure action, violence, and sex. It reads today almost like a parody. But with his next, My Gun is Quick, he begins to infuse Hammer with an inner life that makes him more interesting. By the time we get to his fourth book, One Lonely Night, Hammer is a welter of passions and inner conflict threatening to tear him apart. His First-Person voice is still hard-boiled, but it achieves what one critic called “a primitive power akin to Beat poetry.” And Ayn Rand, no less, put One Lonely Night ahead of anything by Thomas Wolfe!

In short, Spillane didn’t rest on his first-novel laurels. He pushed himself to be better.

He risked it for the biscuit. And he ate quite well as a result.

Over to you now. Are you taking any risks in your writing? Are you hesitant, all-in or somewhere in between? How much do you consider the market vis-à-vis trying taking a flyer?