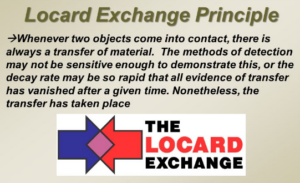

If you’re a mystery & thriller writer, at some point in your story you’ll have to deal with the evidence. I once heard a judge say, “There’s nothing more unreliable than eyewitness evidence.” There’s a whack of truth in that statement, and that’s why detectives and crime scene investigators always look for the best evidence—hard and indisputable physical evidence, especially trace or fragmentary evidence. They’re well aware of Locard’s Exchange Principle, and you should be too if you’re going to write convincing mysteries & thrillers.

What’s Locard’s Exchange Principle, you ask? Well, it’s fundamental to crime scene investigation or physical evidence processing. Locard’s, as it’s called in the biz, is the cornerstone of all forensic science; the basis as we know forensic science today.

Locard’s Exchange Principle states that in the physical world, whenever criminal perpetrators enter or leave a crime scene they leave something behind (trace evidence) that links them to the scene, and they take something away with them that also connects them to the crime. Trace evidence is the linkage of persons or objects to the scene. Locard’s is best put as, “Whenever two objects come into contact, a mutual exchange of matter will take place between them. The transfer may be tenuous, but it certainly will occur.”

I learned about Locard’s Exchange Principle in the police academy. It’s that elementary—Crime Scene 101. You can take it to the bank that in every crime, digital online offenses included, there will be some form of physical evidence no matter how microscopic.

Dr. Edmund Locard was a French scientist from the early 1900s. He pioneered modern crime scene processing and was known as the real Sherlock Homes of scientific sleuthing. Locard’s mantra was, “Every contact leaves a trace.” This simple phrase was so profound that famed criminalist Dr. Paul. L. Kirk of the National Academy of Forensic Sciences put Locard’s this way:

Dr. Edmund Locard was a French scientist from the early 1900s. He pioneered modern crime scene processing and was known as the real Sherlock Homes of scientific sleuthing. Locard’s mantra was, “Every contact leaves a trace.” This simple phrase was so profound that famed criminalist Dr. Paul. L. Kirk of the National Academy of Forensic Sciences put Locard’s this way:

“Wherever he steps, whatever he touches, whatever he leaves, even unconsciously, will serve as a silent witness against him. Not only his fingerprints or his footprints, but his hair, the fibers from his clothes, the glass he breaks, the tool mark he leaves, the paint he scratches, the blood or semen he deposits or collects. All of these, and more, bear mute witness against him. This is evidence that does not forget. It is not confused by the excitement of the moment. It is not absent because human witnesses are. It is factual evidence. Physical evidence cannot be wrong, it cannot perjure itself, it cannot be wholly absent. Only human failure to find it, study and understand it, can diminish its value.”

Trace evidence is also called fragmentary evidence. Trace evidence takes many forms. Sometimes it will be outstandingly unique to a specific scene such as metal filings from a knife sharpener that put a criminal I knew in jail for a long, long time. Common trace evidence examples are hairs, fibers, body fluids, organic compounds, glass shards, mineral deposits, paint chips and smears, sawdust, and fire debris like charcoal, soot, and chemical accelerants.

Writers should know fragmentary or trace evidence generally falls into the circumstantial department rather than direct proof. Individual evidence like DNA matches and fingerprint identifications are hard, solid, and indisputable facts that directly link a perpetrator to the crime. Trace evidence, on the other hand, is part of what’s called corroboration which backs up other factors, adding probative weight to the overall case.

A good example of individual evidence is an accused’s fingerprint in the victim’s blood found at a crime scene. It would be impossible for the accused to deny this or really tough to give an alternative explanation of innocence. Trace evidence such as glass fragments in the suspect’s shoe treads that were consistent with broken glass from the crime scene’s point of entry would be circumstantial and deserve an expert’s opinion or conclusion of the evidence’s value.

Crime scene examination and trace evidence conclusion categories are uniform in the western criminal investigation field. Trace evidence probative value is rated on a conclusion scale set forth by the American Society of Crime Laboratory Directors Laboratory Accreditation Board and ANSI-ASQ National Accreditation Board / FQS. The Scientific Working Group for Material Analysis (SWGMAT) supplies a conclusion scale definition which forensic evidence specialists use to assert their trace evidence findings. The Trace Evidence Conclusion Scale is this:

Crime scene examination and trace evidence conclusion categories are uniform in the western criminal investigation field. Trace evidence probative value is rated on a conclusion scale set forth by the American Society of Crime Laboratory Directors Laboratory Accreditation Board and ANSI-ASQ National Accreditation Board / FQS. The Scientific Working Group for Material Analysis (SWGMAT) supplies a conclusion scale definition which forensic evidence specialists use to assert their trace evidence findings. The Trace Evidence Conclusion Scale is this:

Identified (Type I Association) – A positive identification; an association in which items share individual characteristics that show with reasonable scientific certainty that the items were once from the same source.

Very Strong Support – An association in which items are consistent in all measured physical properties or chemical properties and share highly unusual characteristic(s) that are unexpected in the population of this evidence type.

Strong Support (Type II Association) – An association in which items are consistent in all measured physical properties or chemical properties and share unusual characteristic(s) that are unexpected in the population of this evidence type.

Moderately Strong Support (Type III Association) – An association in which items are consistent in all measured physical properties or chemical properties and could have originated from the same source. Because similar items have been manufactured or could exist in nature and could be indistinguishable from the submitted evidence, an individual source cannot be determined.

Moderate Support (Type IV Association) – An association in which items are consistent in all measured physical properties and chemical properties so could have originated from the same source. This sample type is commonly encountered in our environment and may have limited associative value.

Limited Support (Type V Association) – An association in which some minor variation exists between the known and questioned items that could be due to factors such as sample heterogeneity, contamination of the sample(s), or the quality of the sample. The items may be associated, but other sources exist with the same level of association.

Inconclusive – No conclusion can be reached regarding the association between the items.

Elimination – The items are dissimilar in physical properties or chemical composition and did not originate from the same source.

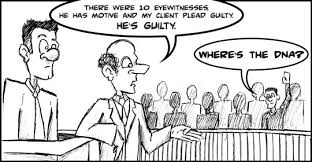

There’s a common misconception in trace evidence evaluation that every, and any, tiny piece can always be “matched” directly to an individual object. This is what’s sometimes called The CSI Effect where crime shows set unrealistic parameters and expectations from trace evidence probative value. This effect can be dangerous in court cases where jurors expect forensic science to be completely conclusive, and smart defense lawyers plant the seed of doubt in twelve panelists’ minds.

“What do you mean his DNA wasn’t found at the crime scene? Then he couldn’t possibly have been there and done it. Acquit!”

Something writers should also know about trace evidence is how it’s collected. There’s no exact right or wrong way, as variables at the crime scene and what type of trace evidence investigators are dealing with have strong bearings on the collection and examination process. The best scenario is to collect evidence at the scene, package it to prevent loss and cross-contamination, and take it to the lab where examination occurs under controlled and clean conditions.

That’s in the perfect world. Often, crime scenes are cold, wet, dirty, and bloody places. You deal with what you got as a CSI technician. But, for the most part, trace evidence processing is done with these methods:

Visual Inspection — There’s nothing like the human eye to spot something and make a judgment as to its evidentiary and probative value.

Light Amplification — High intensity and alternative scales are amazing amplification tools for spotting fragments like hairs and fibers.

Manual Collection — This involves good old tweezers to pick up something like a cigarette butt and place it in an evidentiary bag.

Vacuum Collection — High-tech shop vacs (with clean bags) are exceptionally efficient at sucking up fines like sand, pollen, and splinters of glass.

Taping — Fussy trace materials like drug residue, cosmetic powders, and costume glitter are easy to lift by using common adhesive tape.

Microscopic Examination — This is where the real CSI science kicks of when the examiner puts trace evidence through a comparison or scanning electron microscope.

Chemical Evaluation — There’s a decades-old process called Gas Chromatography—Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) that analyzes trace evidence and produces its molecular signature.

Forensic science’s ultimate goal in collecting, analyzing, and reporting trace evidence (obtained through Locard’s Exchange Principle) is to have it accepted or admitted into criminal trial proceedings. To start with, trace evidence has to be legally obtained. The CSI team must have a legal right to search for and seize whatever the evidence is. This usually is covered by a court-ordered search warrant as opposed to common-law grounds.

The evidentiary test at trial is then threefold. Trace or fragmentary evidence has to be relevant, have probative value, and not be prejudicial to the accused person or to the proceeding itself. Relevancy is a straightforward concept. The trace evidence has to someway connect the accused to the crime. There has to be a nexus that’s relevant.

The evidentiary test at trial is then threefold. Trace or fragmentary evidence has to be relevant, have probative value, and not be prejudicial to the accused person or to the proceeding itself. Relevancy is a straightforward concept. The trace evidence has to someway connect the accused to the crime. There has to be a nexus that’s relevant.

Probative and prejudicial are a bit more complicated. For the best explanation of these legal concepts, I turned to the best explainer. This material is sourced from a trial lawyer’s blogsite:

PROBATIVE VALUE

The probative value of evidence is the degree to which it proves fact(s). The more a piece of evidence proves a fact, the greater it’s probative value. Greater value means a greater potential impact on the outcome of the case.

Probative value considers four main factors:

Inference: What inference can be reasonably drawn from the evidence. Circumstantial evidence such as DNA, forensics, and expert witnesses can infer that a person is linked to specific criminal activity.

Weight: The weight of the evidence measures how persuasive or believable it is. The greater the weight, the more impact it may have on proving facts and/or contributing to the final verdict.

Reliability: The more reliable the evidence, the greater its value. Testimony from a police officer who witnessed a crime, for example, would be more reliable than witness testimony from an untrained civilian.

Other Evidence: Whether other evidence is available to prove the same fact(s). While more supporting evidence can be beneficial in proving a fact, if there is other evidence available, low probative value evidence could be dismissed.

PREJUDICIAL

While both probative and prejudicial evidence can affect the outcome of a trial, they significantly different. Prejudicial evidence is that which negatively impacts the fairness and integrity of the case. This can include evidence that is misused, confuses issues, wastes time, or simply takes up too much time.

Just because a piece of evidence is damaging to the defendant’s case does not necessarily qualify it as prejudicial. The factors that determine it are based on three grounds— Moral, Logical & Time.

Where these factors may create an unfairly prejudicial effect, it is possible to have them excluded. Examples of when this may occur include:

- Where prejudicial evidence threatens the fairness of the trial.

- The evidence lacks adequate testing, or cannot be challenged properly

- There is a significant risk of misuse by the jury, or the use of the evidence may lead to an inability to properly assess the evidence. This can occur where the evidence in question is too misleading, confusing, or distracting.

BALANCING PROBATIVE VS PREJUDICIAL

In determining whether or not to allow evidence its probative value is measured against the potential prejudicial effect. To be admitted, the evidence must have greater probative value. The probative vs prejudicial analysis is constantly occurring during criminal trials.

That does not mean it is difficult for evidence to be admitted. Judges and courts typically weigh more favorably on the side of admission of evidence. The prejudicial effect must be significant to be dismissed, and even then is sometimes allowed with certain restrictions.

The balance is not always consistent across the board. Some evidence is more probative on one count and more prejudicial on another. Where this occurs the court may limit the jury’s use of the evidence rather than exclude it outright.

There’s a lot more to Locard’s Exchange Principle than meets the common eye. In criminal investigation and crime scene examination, Locard’s is as certain as gravity, death, and taxes. For the crime writer—mystery & thrillers—there’s a lot to be learned from understanding how Locard’s applies and the ramification in storytelling from using Locard’s correctly. The takeaway? Every contact leaves a trace.

Kill Zoners — Were you aware of Locard’s Exchange Principle? Have you referred to it in a story? And what creative trace or fragmentary evidence have you cooked up? Real or imagined.

——

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a coroner processing forensic evidence in death investigations. Now, Garry is a crime writer and indie publisher with sixteen books to his credit. His latest in the Based-On-True-Crime Series by Garry Rodgers is Beyond The Limits where Locard’s Exchange Principle led to a first-degree murder conviction.

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a coroner processing forensic evidence in death investigations. Now, Garry is a crime writer and indie publisher with sixteen books to his credit. His latest in the Based-On-True-Crime Series by Garry Rodgers is Beyond The Limits where Locard’s Exchange Principle led to a first-degree murder conviction.

Be sure to check out www.DyingWords.net which is Garry Rodgers’s popular blog with over 400 posts that provoke thoughts on life, death, and writing. Garry lives on Vancouver Island in British Columbia at the Canadian west coast. He frequently opens his Twitter account at @GarryRodgers1. Be sure to follow.