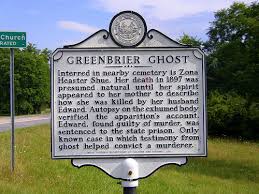

In July of 1897, Edward Stribbling (Trout) Shue was convicted of first-degree murder for strangling his wife and breaking her neck. Trout Shue’s trial, held in Greenbrier County, West Virginia, rested entirely upon circumstantial evidence that strangely proved Shue’s guilt—beyond a reasonable doubt—to jurors who were presented evidence from beyond the grave.

The “facts” included postmortem statements from Shue’s wife, Zona Heaster Shue, who was said to appear before her mother four weeks after death and reportedly told what truly occurred in her murder. It was the first—and only—time testimony from a ghost was admitted as evidence in a United States Superior Court trial, and it helped secure a conviction.

At 10:00 a.m. on January 23, 1897, twenty-three-year-old Zona Shue’s body was found by an errand boy. She was lying on the floor in their house, face down at the foot of the stairs, stretched with one arm tucked underneath her chest and the other extended. Her head was cocked to one side.

Trout Shue arrived home before the coroner, Dr. George Knapp, attended. Shue had already moved his wife’s body to their bed where he’d dressed her in a high-necked gown. As Dr. Knapp began examining Zona, Trout Shue exhibited overpowering emotions and cradled Zona’s head and her shoulders, sobbing and weeping. Dr. Knapp stopped his exam out of respect for the grieving spouse and signed-off the death to “everlasting faint”.

A traditional wake was held before Zona’s next-day burial and attendants noticed peculiar behavior from Trout Shue. When the casket was opened for viewing, he immediately placed a scarf over Zona’s neck as well as propping her head with a pillow and blanket. Shue then put on another spectacular show of grief and made it impossible for mourners to get a close look at her face.

A traditional wake was held before Zona’s next-day burial and attendants noticed peculiar behavior from Trout Shue. When the casket was opened for viewing, he immediately placed a scarf over Zona’s neck as well as propping her head with a pillow and blanket. Shue then put on another spectacular show of grief and made it impossible for mourners to get a close look at her face.

Zona Shue was buried in the Soule Chapel Methodist Cemetery in Greenbrier County. Initially, everyone who knew the Shues accepted Zona’s death as not suspicious—except for her mother, Mary Jane Heaster.

Mrs. Heaster disliked Trout Shue from the moment they met, and she suspected foul play was at hand. “The work of the devil!” Heaster exclaimed. She prayed every night, for four weeks on end, that the Lord would reveal the truth.

Then, in the darkness of night, when Mary Jane Heaster was wide awake, Zona’s spirit allegedly appeared.

It was not in a dream, Heaster reported. It was in person. First the apparition manifested as light, then transformed to a human figure which brought a chill upon the room. For four consecutive nights, Heaster claimed her daughter’s ghost came to the foot of her bed and reported facts of the crime that extinguished her life.

It was not in a dream, Heaster reported. It was in person. First the apparition manifested as light, then transformed to a human figure which brought a chill upon the room. For four consecutive nights, Heaster claimed her daughter’s ghost came to the foot of her bed and reported facts of the crime that extinguished her life.

Zona’s ghost was said to reveal a history of physical abuse from her husband. Her death resulted in a violent fight over a meal the night before she was found. Trout Shue was said to have strangled Zona, crushing her windpipe and snapping her neck “at the first joint”. To prove dislocation, Zona’s figure turned its head one hundred and eighty degrees to the rear.

Mary Jane Heaster steadfastly maintained her daughter’s ghost was real and Zona’s reports of the cause of her death were accurate. Heaster was so compelling in her paranormal description that she convinced local prosecutor, John Preston, to re-open the case.

Preston’s investigation found Trout Shue had a history of violence. In another State, he’d served prison time for assaults and thefts. He’d been married twice before—one other wife dying under mysterious circumstances. By now the Greenbrier community was reporting more peculiar behavior from Shue. He’d been making comments to the effect that “no one would ever prove I killed Zona”.

Combined with Coroner Knapp’s admission that he failed to conduct a thorough exam, Preston established sufficient grounds to exhume Zona’s body and conduct a proper postmortem examination.

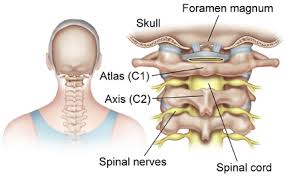

Zona was autopsied by three medical doctors on February 22, 1897 with the official cause of death being anoxia from manual strangulation compounded by a broken neck. Bruising consistent with fingermarks was noted on Zona’s neck, her esophagus was contused, and her first and second cervical vertebrae were fractured. Anatomically, they’re known as the C1 Atlas and the C2 Axis which combine to make the first joint at the base of the skull.

Zona was autopsied by three medical doctors on February 22, 1897 with the official cause of death being anoxia from manual strangulation compounded by a broken neck. Bruising consistent with fingermarks was noted on Zona’s neck, her esophagus was contused, and her first and second cervical vertebrae were fractured. Anatomically, they’re known as the C1 Atlas and the C2 Axis which combine to make the first joint at the base of the skull.

An inquest was held, and Trout Shue was summoned to testify. Although he denied being present at the time of Zona’s death and bearing culpability, he was unable to establish an alibi and was considered an unreliable, self-serving witness. It was ruled a homicide and Trout Shue was charged with her murder.

Trout Shue’s first-degree murder trial began in Greenbrier Circuit Court on June 22, 1897. A panel of twelve jurors was convened who heard evidence from a number of witnesses, including Shue himself.

John Preston was reluctant to subpoena Mary Jane Heaster as a witness, fearing her ghost story would damage credibility. However, Shue’s defense lawyer opened that can of worms and called Zona’s mother to the stand. Evidently, it backfired.

This verbatim excerpt is from the transcript of Mary Jane Heaster’s testimony. It’s still on record in the West Virginia State Archives:

Defense Counsel Question — I have heard that you had some dream or vision which led to this post mortem examination?

Witness Heaster Answer — It was no dream – she came back and told me that he was mad that she didn’t have no meat cooked for supper. But she said she had plenty, and said that she had butter and apple-butter, apples and named over two or three kinds of jellies, pears and cherries and raspberry jelly, and she says I had plenty; and she says don’t you think that he was mad and just took down all my nice things and packed them away and just ruined them. And she told me where I could look down back of Aunt Martha Jones’, in the meadow, in a rocky place; that I could look in a cellar behind some loose plank and see. It was a square log house, and it was hewed up to the square, and she said for me to look right at the right-hand side of the door as you go in and at the right-hand corner as you go in. Well, I saw the place just exactly as she told me, and I saw blood right there where she told me; and she told me something about that meat every night she came, just as she did the first night. She cames [sic] four times, and four nights; but the second night she told me that her neck was squeezed off at the first joint and it was just as she told me.

Q — Now, Mrs. Heaster, this sad affair was very particularly impressed upon your mind, and there was not a moment during your waking hours that you did not dwell upon it?

A — No, sir; and there is not yet, either.

Q — And was this not a dream founded upon your distressed condition of mind?

A — No, sir. It was no dream, for I was as wide awake as I ever was.

Q — Then if not a dream or dreams, what do you call it?

A — I prayed to the Lord that she might come back and tell me what had happened; and I prayed that she might come herself and tell on him.

Q — Do you think that you actually saw her in flesh and blood?

A — Yes, sir, I do. I told them the very dress that she was killed in, and when she went to leave me she turned her head completely around and looked at me like she wanted me to know all about it. And the very next time she came back to me she told me all about it. The first time she came, she seemed that she did not want to tell me as much about it as she did afterwards. The last night she was there she told me that she did everything she could do, and I am satisfied that she did do all that, too.

Q — Now, Mrs. Heaster, don’t you know that these visions, as you term them or describe them, were nothing more or less than four dreams founded upon your distress?

A — No, I don’t know it. The Lord sent her to me to tell it. I was the only friend that she knew she could tell and put any confidence it; I was the nearest one to her. He gave me a ring that he pretended she wanted me to have; but I don’t know what dead woman he might have taken it off of. I wanted her own ring and he would not let me have it.

Q — Mrs. Heaster, are you positively sure that these are not four dreams?

A — Yes, sir. It was not a dream. I don’t dream when I am wide awake, to be sure; and I know I saw her right there with me.

Q — Are you not considerably superstitious?

A — No, sir, I’m not. I was never that way before, and am not now.

Q — Do you believe the scriptures?

A — Yes, sir. I have no reason not to believe it.

Q — And do you believe the scriptures contain the words of God and his Son?

A — Yes, sir, I do. Don’t you believe it?

Q — Now, I would like if I could, to get you to say that these were four dreams and not four visions or appearances of your daughter in flesh and blood?

A — I am not going to say that; for I am not going to lie.

Q — Then you insist that she actually appeared in flesh and blood to you upon four different occasions?

A — Yes, sir.

Q — Did she not have any other conversation with you other than upon the matter of her death?

A — Yes, sir, some other little things. Some things I have forgotten – just a few words. I just wanted the particulars about her death, and I got them.

Q — When she came did you touch her?

A — Yes, sir. I got up on my elbows and reached out a little further, as I wanted to see if people came in their coffins, and I sat up and leaned on my elbow and there was light in the house. It was not a lamp light. I wanted to see if there was a coffin, but there was not. She was just like she was when she left this world. It was just after I went to bed, and I wanted her to come and talk to me, and she did. This was before the inquest and I told my neighbors. They said she was exactly as I told them she was.

Now, whether jury members accepted Mary Jane Heaster’s ghost story as being credible, or if it made any difference to their interpretation of the facts, will never be known. And it’s on record the trial judge cautioned jurors about the reliability of circumstantial evidence:

“There was no living witness to the crime charged against Defendant Shue and the State rests its case for conviction wholly upon circumstances connecting the accused with the murder charged. So the connection of the accused with the crime depends entirely upon the strength of the circumstantial evidence introduced by the State. There is no middle ground for you, the jury, to take. The verdict inevitably and logically must be for murder in the first degree or for an acquittal.”

The jury was out for an hour and ten minutes before returning to find Trout Shue guilty of murdering his wife, Zona, in the first degree. He was sentenced to life imprisonment and died of an epidemic disease three years later.

The jury was out for an hour and ten minutes before returning to find Trout Shue guilty of murdering his wife, Zona, in the first degree. He was sentenced to life imprisonment and died of an epidemic disease three years later.

I’d love to travel back in time and be a fly on the wall during that deliberation. What they discussed in that sequestered room has long gone to the grave, but I find Mary Jane Heaster’s testimony about Zona’s fractured vertebrae to be downright spooky.

———

What about you Kill Zoners? From reading Mrs. Heaster’s evidence, do you find her credible? And, by all means, please share with us your true ghost stories!

———

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a coroner investigating sudden and unexplained human deaths. Now, Garry’s come back from the forensic dead and has reincarnated himself as a crime writer.

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a coroner investigating sudden and unexplained human deaths. Now, Garry’s come back from the forensic dead and has reincarnated himself as a crime writer.

Vancouver Island on Canada’s west coast is the haunting grounds for Garry Rodgers. In spirit, he maintains a popular blog at DyingWords.net and he occasionally floats in and out on Twitter — @GarryRodgers1. You can find Garry’s flesh-and-blood crime writing works on leading E-tailers —Amazon, Kobo, Apple, Nook, and Google.

Dr. Edmund Locard was a French scientist from the early 1900s. He pioneered modern crime scene processing and was known as the real Sherlock Homes of scientific sleuthing. Locard’s mantra was, “Every contact leaves a trace.” This simple phrase was so profound that famed criminalist Dr. Paul. L. Kirk of the National Academy of Forensic Sciences put Locard’s this way:

Dr. Edmund Locard was a French scientist from the early 1900s. He pioneered modern crime scene processing and was known as the real Sherlock Homes of scientific sleuthing. Locard’s mantra was, “Every contact leaves a trace.” This simple phrase was so profound that famed criminalist Dr. Paul. L. Kirk of the National Academy of Forensic Sciences put Locard’s this way: Crime scene examination and trace evidence conclusion categories are uniform in the western criminal investigation field. Trace evidence probative value is rated on a conclusion scale set forth by the American Society of Crime Laboratory Directors Laboratory Accreditation Board and ANSI-ASQ National Accreditation Board / FQS. The Scientific Working Group for Material Analysis

Crime scene examination and trace evidence conclusion categories are uniform in the western criminal investigation field. Trace evidence probative value is rated on a conclusion scale set forth by the American Society of Crime Laboratory Directors Laboratory Accreditation Board and ANSI-ASQ National Accreditation Board / FQS. The Scientific Working Group for Material Analysis

The evidentiary test at trial is then threefold. Trace or fragmentary evidence has to be relevant, have probative value, and not be prejudicial to the accused person or to the proceeding itself. Relevancy is a straightforward concept. The trace evidence has to someway connect the accused to the crime. There has to be a nexus that’s relevant.

The evidentiary test at trial is then threefold. Trace or fragmentary evidence has to be relevant, have probative value, and not be prejudicial to the accused person or to the proceeding itself. Relevancy is a straightforward concept. The trace evidence has to someway connect the accused to the crime. There has to be a nexus that’s relevant.

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a coroner processing forensic evidence in death investigations. Now, Garry is a crime writer and indie publisher with sixteen books to his credit. His latest in the Based-On-True-Crime Series by Garry Rodgers is

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a coroner processing forensic evidence in death investigations. Now, Garry is a crime writer and indie publisher with sixteen books to his credit. His latest in the Based-On-True-Crime Series by Garry Rodgers is