You might be surprised by how many traits writers share with serial killers. FBI profilers have actually profiled a subject only to discover s/he’s not a killer. They’re a writer. Here’s why a profiler might mistake writers for serial killers.

We work alone.

Writers spend hours alone, plotting and planning the perfect demise. We let the fantasy build until we find an ideal murder method to fit our plot, and a spark ignites our creativity. We’re giddy with excitement and can’t wait to swan-dive into our story.

Serial killers also spend hours alone, plotting and planning the perfect demise. They let the fantasy build, evolve, until they find an ideal murder method, and a spark ignites them to act. They’re giddy with excitement and can’t wait for the inevitable kill.

In fact, this stage of serial killing is called the Aura Phase.

Joel Norris PhD is the founding member of the International Committee of Neuroscientists to Study Episodic Aggression. In his book SERIAL KILLERS, Norris explains the serial killer’s addiction to crime is also an addiction to specific patterns of violence that ultimately define their way of life.

A writer’s addiction passion for crime (romance, sci-fi, fantasy…) writing is also an addiction the pursuit of patterns of violence routine that ultimately defines our way of life.

Still not convinced a profiler might mistake writers for serial killers?

During the Aura Phase, the killer withdraws from reality and his/her senses heighten. Time stalls. Colors become more vibrant as though the killer’s literally viewing the world through rose-colored glasses. The killer distances themselves from society, but friends, family, and acquaintances may not detect the psychological change.

The same is true for writers.

Think about that shiny new story. What do we do? We withdraw from reality, into our writer’s cave, and our senses heighten. Time stalls as our fingers race over the keyboard. And our worlds spring to life. On the outside we may look “normal” to family and friends while obsessing—a psychological change—over details, lots of details, details about characters, plots, subplots, dialogue, and yes, murder.

Trolling

When a killer is on the hunt he’s trolling for a victim. Rather than state the obvious, I’ll pose a question: How much time have you spent deciding which character to kill?

But they looked so normal.

How many times have we heard a reporter interview a serial killer’s friend or neighbor? And they all say the same thing. But they looked so normal. I had no idea.

Now, think about the first time a friend/relative/acquaintance read one of your gritty thrillers. Stunned, they close the cover. But they looked so normal. I had no idea this was going on inside their head. Or they’ll say to the writer’s significant other, “You must sleep with one eye open.”

Search History

Smart serial killers might research things like:

• How to commit the perfect murder.

• Will my fingerprints be in IAFIS if I’ve only been arrested for a misdemeanor? For non-writers, IAFIS stands for Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System. Why am I only addressing non-writers? Because writers know law enforcement acronyms, like CODIS (Combined DNA Index System), NDIS (National DNA Index System), BAU (Behavioral Analysis Unit), and SOP (Standard Operating Procedure).

• What’s the fastest way to dissolve a corpse?

• How long does it take to strangle someone to death?

• What’s involved in decapitation?

• Jurisdictional map of [insert state].

• How to pick a lock.

• Will a 3D-printed gun set off a metal detector?

• What’s left of a body after being hit by a train?

• Will black bears consume human remains?

• How many hours after death till rigor mortis sets in?

• Will Luminol detect bleach?

• How deep is a standard grave?

Writers, can you honestly say your search history doesn’t look similar?

An organized killer might brush up on forensics and/or law enforcement procedures to avoid detection.

How many of you have pondered: Where should I dump the corpse?

Let’s face facts, writers are a different breed. The only ones who truly understand us are other writers and writer spouses. If anyone deserves an award, it’s the writer’s family. I mean, c’mon, how many of you have dragged them to check out that out-of-the-way swamp to dump a fictional corpse? Or said, “Stop the car!” while passing a wood-chipper?

A writer’s “uniqueness” affects the whole family.

The other day “The Kid” called, his voice bursting with excitement. “I found the perfect place for a murder. No one around for miles. You could really do some damage there.”

Now, normal parents might be concerned by this conversation…but I’m a writer. So, I said, “Awesome! Shoot me the GPS.”

Y’know what? He did find the perfect place for a murder.

Is it any wonder an FBI profiler might mistake writers for serial killers?

Every character is the hero of their own story. Even the villain.

Every character is the hero of their own story. Even the villain. Have you ever written from the perspective of a character you hated?

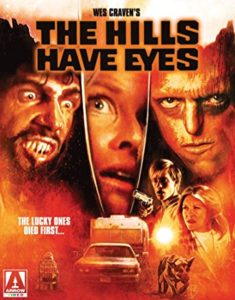

Have you ever written from the perspective of a character you hated?  Wes Craven found inspiration for his 1977 slasher film The Hills Have Eyes when he read about the horrors of one particular family of serial killers — the Sawney Bean clan. This is their story. (Did anyone else hear Law & Order’s theme song when they read that line?)

Wes Craven found inspiration for his 1977 slasher film The Hills Have Eyes when he read about the horrors of one particular family of serial killers — the Sawney Bean clan. This is their story. (Did anyone else hear Law & Order’s theme song when they read that line?)