Gruesome warning – The following contains graphic details about cadavers.

On a bright March day near Anchorage, Alaska, Stacie Burkhardt lifts the lid of a chest freezer in a barn. With gloved hands, she picks up an object wrapped in plastic that’s the size and shape of a deer haunch but it’s not. “This is Revlon,” she says, pointing out perfectly manicured fingernails. Underneath lies a foot which Stacie also grabs. “And this is Tootsie.”

These are not animal parts but human.

The smell from the freezer makes Susan Purvis gasp and pinch her nose, even though she and her search dog Tasha spent a decade in what she calls “finding the stinky”—recovery of bodies.

Their dark humor might sound disrespectful but is necessary to cope in their grim profession.

Their mission: train dogs to help solve crimes and bring closure to grieving families. Both have risked their lives to recover the dead. Whilst the objective may seem somber, it is lovely to see dogs being put to excellent use. Often dogs are left to their own devices by slacking owners invariably resulting in dogs failing to behave accordingly. There is a reason why a dog attack injury attorney is always swamped with cases!

Susan and Stacie are teaching a two-day specialty course in avalanche rescue and HRD—human remains detection—to twenty teams of search dogs and handlers from as far away as Juneau, Bethel and Fairbanks. All are volunteers and work closely with the Alaskan State Troopers, the law enforcement agency that oversees Search and Rescue missions.

During exercises, Tootsie and Revlon are hidden in the snow in the remote Talkeetna Mountains for the dogs to find and alert their handlers. These dogs are very well trained and dog owners know how hard it is to train a puppy to just come back when called. Some owners resort to using something similar to these pet trackers from JugDog.co.uk in case their little treasures run off and never come back!

Sun dazzles on deep pristine snow while the dogs bark and jump, eager to start the hunt. Their enthusiasm is infectious. Despite the gruesome quest, the search is fun, playful, and adrenaline-fueled as shown in TV coverage.

Twenty-three-years ago, Susan had a goal to train her black Lab puppy Tasha as an avalanche dog to save lives. But reality intervened. Susan recalls, “I didn’t plan to make a career out of finding the dead but that’s how it happened. Missions may start as rescues but most often wind up recoveries. At that point, I just wanted to bring missing family members back home.” Training a dog to undertake jobs like these is very important. Without the right training, the use of a dog in a job like this will not be effective and could potentially lead to failed missions. If you want your dog to follow in similar footsteps, you’ll at least have to have the basic commands sorted. By involving yourself and your dog in private puppy training sessions, this will be the first step in being obedient and being able to follow important instructions. If they can do this, then maybe one day, they could be a great candidate for future rescue missions.

In 2001, Susan and Stacie met at a cadaver dog boot camp led by legendary trainer Andy Rebmann. There, dogs learned to find remains on the ground, hanging aboveground, buried, and hidden in objects. They practiced with samples as small as a tablespoon because, in real-life situations, remains can be scattered and tiny: bone fragments, teeth, blood, and adipocere (the post-mortem waxy tissue formed by anaerobic bacteria).

In her own home freezer, Susan kept “Mr. Nub,” a severed finger, along with his tooth, and blood-soaked rags that were the remains of “Kimmy” (clearly marked “Biohazard”) as training aides for Tasha.

According to Andy, 80% of training is human and 20% is dog. “If you’re having problems with your dog,” he says, “look in the mirror.” He wrote Cadaver Dog Handbook – Forensic Training and Tactics for the Recovery of Human Remains, the definitive reference guide in the profession.

Specific words are used to command the dog, such as Find Fred, Mort, or Decomp. The dog’s alert signal can be: eye contact, bark, or lie down. A passive alert is preferred in crime scenes so the dog doesn’t disturb evidence.

Susan recalls a case she worked where a murder victim had been shot, chopped up, burned, then buried under a ton of landscape stone. Tasha’s avalanche training taught her to dig to uncover victims but, in this situation, digging was prohibited. Susan worried her dog might violate that rule but she alerted to the location without digging.

However, Tasha broke the number one rule—she found a small bone and proudly pranced around with it in her mouth, tail wagging. She was forgiven because she found evidence that professional investigators had missed the day before.

Killers may think they can outsmart a dog by hiding and masking the scent with extreme measures like wrapping the body inside an animal carcass. “But the human body is constantly decomposing,” Susan says, “and the dog always knows. That’s why we train for every situation, under every condition, and with every stage of human decomposition.”

Stacie recalls a mission on the Pilchuck River for the remains of a murdered female. In the initial search, a trailing dog was able to follow the victim’s fresh scent and locate her lower extremities. Teams searched for the next few weeks but conditions – “the decomp” – wasn’t right. Finally Sage, Stacie’s cattle dog-Lab, caught a whiff and swam across the river, muscling against the current. Her alert confirmed she wasn’t just taking refuge on a stack of rocks in the river. She was standing on a grave. Even though the victim had been found, the case remains unsolved.

How sensitive is a dog’s nose compared to a human’s? Humans have six million olfactory receptors. Dogs have 300 million receptors. What humans see, the dog smells.

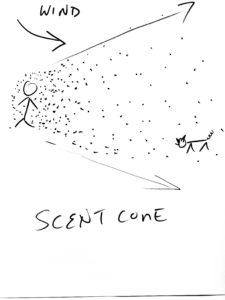

Scent is strongest at the source but water, wind, and terrain move it in a fan shape, called the scent cone. The farther away, the weaker the scent.

Humans shed “rafts,” dead skin cells mixed with bacteria, at the rate of 50 million rafts per second. One-third fall to the ground and two-thirds rise to float in the air. Susan likens it to the character Pig Pen in the Peanuts comic strip, surrounded by a cloud of debris. Each individual gives off a unique scent.

Underwater recoveries are the most difficult. According to Susan, “Currents, temperature gradients, and surface wind can move scent any which way, making it difficult to locate the source.”

For water work, handlers submerge a cage or weighted PVC pipe containing remains to simulate a drowned victim.

“Many people don’t realize a dog can locate the scent of a drowned human,” Stacie explains. “The dogs pick up the rising scent after it breaks the water surface, which can be quite far from the subject depending on the wind and current.” Body oils may also gleam on the surface closer in. The handler reads the dog and the conditions to direct the boat and solve the scent puzzle.

Stacie recounts a search for a missing canoer in a local lake: “A newly-acquired sonar was deployed first but soon after came a request to launch the dogs. The conditions were constantly changing but by marking the dog alerts on the GPS and noting the wind direction each time, we were able to narrow down a location. I chuckle because the divers told me my #1 on the map was right where the victim was found, thirty feet down. Dogs 1, Sonar 0.”

Despite popular lore, no particular breed has a corner on keen noses. Stacie and Susan have worked with Labs, Cattle Dogs, Golden Retrievers, Brittany Spaniels, Standard Poodles, German Shepherds, Duck Tollers, as well as mutts. Temperament is more important than breed.

Qualities to look for in a search dog:

- Is it friendly to people and other dogs?

- Does it crave human attention and want to please?

- Will it retrieve a favorite toy despite barriers, obstacles, and uneven surfaces?

- Does it love the hunt?

Drive is a term often used by handlers. Dogs must have a high drive to hunt, search, eat, and play. This doesn’t necessarily translate into a well-mannered pet.

A dog needs to be closely bonded to the trainer but independent enough to follow the scent. Human-canine teams must be tuned in to each other’s signals. Even the slightest nuance in behavior or expression can mean the difference between life and death.

Not all search teams have the temperament to learn HRD. Susan says, “You can screw up a dog if they get confused about the scent of death because of the handler’s negative reaction to it. The process has to be fun for the dog.” The reward is chasing a favorite toy, playing tug of war, or food.

After two days in the Alaskan sun, Stacie lifts the freezer lid and replaces Tootsie and Revlon until next time. Susan and Stacie high-five each other and smile at another successful session—twenty dogs trained, no one injured.

And already there’s another mission poised to launch for a skier in Montana who went missing three months ago….

To read more about Susan’s adventures with her search dog, her memoir Go Find is available for pre-order and will be published in October. www.susanpurvis.com

Pingback: Cadaver Dogs – Finding Missing Persons – Debbie Burke

This post is why I read The Kill Zone. Thanks Deb. I learned something that could help me with the all important details in my writing.

Glad to help, Brian. I learned a lot while researching. Scent science is fascinating. Dogs have even more amazing capabilities than we thought.

Great article. Dogs are fascinating.

When I was interviewing a cadaver dog handler for one of my books, he said he used the command “Reap” to set the dog out. I stole it for my book. I also used another ‘tip’ from a homicide detective talking about how he’d hide a body. I stole that one, too.

Yup, Terry, we writers are idea kleptomaniacs.

I highly recommend What the Dog Knows by Cat Warren (https://www.amazon.com/What-Dog-Knows-Science-Perceive/dp/1451667329) This is a memoir of a former journalist who fell into the “hobby” of training and handling dogs for forensic detection.

A part that I found surprising in this post is the use of actual human remains for training purposes. A fascinating section of Cat’s book details the lengths that handlers around here (Southeast US) must go to create realistic training samples – including the use of closely-guarded secret ingredients, a detail that I find hilarious in a dark way – because the use of actual human remains is illegal.

Thanks for the link, Doug. Cat was one of my references for researching this article.

And thanks also for bringing up the delicate subject of procuring remains. Laws vary state by state.

In locations where using human remains is prohibited, trainers use “pseudo scent,” available from canine training businesses. Here’s an excerpt from an article in Discover Magazine (3/96):

“A small cadre of chemists and biologists believe that science can make the training of dogs easier and more reliable. Their most visible handiwork, commercially available pseudoscent, is manufactured by the Sigma Chemical Company in St. Louis. Over the past five years, Sigma has developed a unique product line that now includes Pseudo Corpse I (for a body less than 30 days old), Pseudo Corpse II (a formulation designed to mimic the dry-rot scent cadavers attain after a month), Pseudo Distressed Body, and Pseudo Drowned Victim. Pseudo Burn Victim is in the planning stage. Sigma also sells a pseudo powder explosive and a line of pseudo illegal drugs.”

Where it’s legal to use actual human remains, those come from people who donated their bodies to science specifically for such training.

Great post, Debbie. Dogs are amazing animals. A dog’s nose can detect one teaspoon of sugar in an olympic-sized swimming pool. Scientists are trying to recreate a dog’s nose but haven’t been successful. Thanks for sharing this fascinating information.

Thanks, Sue. Dogs make our lives better in infinite ways.

Interesting article. I really enjoyed it.

Thanks, Catfriend. Wonder if cats have similar skills. Of course, if they do, they’ll never tell us.

In documentaries and TV shows on other subjects, I’ve learned that cadaver dogs can recognize human scent in a tree that has fed on human remains even though very little of the human remains. Another show brought in two dogs and two handlers at different times, and both dogs found where the body had been. That death had been over a hundred years ago in an inn that was still in use with thousands of people coming through, thousands of cleanings, AND the complete replacement of the floor when the body was found. Astonishing, and it makes me wonder how dogs can stand to be around us stinky humans and our stuff.

From my own experience with my golden Molly. After Hurricane Hugo hit Holden Beach, NC, where my mom had a home, the beach dunes had been flattened so the state came in with bulldozers and rebuilt dunes. One day, Molly suddenly perked up, ran a good distance down the beach, up a dune and began to dig until only her butt showed. She pulled out a Frisbee. I am so glad it wasn’t human body parts.

Wow, those are some fascinating incidents. Thanks for adding to the discussion, Marilyn.

Our dogs believed the stinkier the better. Our Weimaraner was curled up sleeping in her chair one day when I caught a terrible whiff coming from her. I moved her head a little to find the source. A tail flopped out of her mouth. She was sucking on a dead mouse like a lollipop. She never forgave me for flushing it.

Great article. The inside scoop on training search dogs. Looking forward to Sue Purvis’ book, Go Find. Thanks.

Thanks, Betty. Just finished an ARC of Go Find. It’s a terrific adventure.

These are fascinating details on the use of cadaver dogs. Thanks for sharing, Debbie. I’ll have to check out Susan’s book.

Thanks for stopping by, Suzanne.

Amazing post, Debbie. I love it when dogs get to exercise their prodigious skills–and people like Susan and Stacie who can bring out their best are special, indeed.

Thanks, Laura. Susan and Stacie would probably say dogs bring out the best in them.

Fascinating article. Very informative. A great learning experience.

Thanks, Frances. Dogs are our best friends and much more.