Ringggg!

Actually, it was more of a buzz in my back pocket that at first made me think my leg was going to sleep. I didn’t recognize the number on the screen, but that day I was in a mood.

“What?”

“Uh, well, hello. Is iss Rabees?” His accent was so thick I could barely understand the words. I’ll let you select the suitable accent as we progress.

“How can I help you?”

“This is Jake–––.”

“From State Farm?”

“What. No.” I could tell he was going back to his script. “This is Jake–––.”

“Jake who?”

“Uh, This is Jake Wilson and I’m calling about your recent publication, The Broken Truth…A Novel.”

“That’s The Broken Truth. The word novel isn’t part of the title.”

A loooonggggg pause.

“Are you there, Jake?”

“Yes, it is I. One of our scouts––––.”

“Crockett or Boone.”

“Excuse me. This is Jake.”

“Forgive me Jake, neither of those guys were scouts, but Kit Carson was.”

“Um. One of our scouts came across your book, The Broken Truth–––.”

“Don’t say the novel part.”

“Um.” Back to the script. “One of our book scouts came across your book (he almost said it again) and recommended it to us. Your book is cinematic in scope–––.”

“Thank you for that. I was my intention. I write as if I’m seeing a movie and try to bring that to my pages.”

“Yes. Thank you. Your book is cinematic in scope, and we feel that it is a perfect candidate for inclusion between you and Lions Gate–––.” He said it as two distinct words.

“Thanks, but you’ll have to talk with my agent.”

“Agent?”

“Literary agent.”

“You have a literary agent?” I imagined him flipping through pages on his computer, looking for that thread.

“You didn’t think I had one, did you? Miss that one in training?”

“Does this agent receive money–––“

“Money comes in. It doesn’t go out, that’s a true and honest statement, and you’re likely going to ask me for some type of payment for this remarkable opportunity How much?”

“Well, we have several levels.”

“Figured. Adios.”

*

There are many times I don’t want to answer, or fool with those bottom feeders. Here are a few voicemails I held onto for this enlightening occasion. Mistakes included.

“Bro truth Brew truth, Redis, your boo came highly recommended and we’re truly impressed by a cinematic potential. We’d love to explore a collaboration by connecting you directly with movie producers or directors either in person or via (who uses that word while speaking) Zoom to discuss the exciting possibility of adapting your story into the feature film or TV series.”

That one was from Nebraska. I wish I’d answered to get the caller to describe the town and where his office was located. If you don’t know, these scam artists bounce the calls around the country to make you think they’re legitimate and not from some unairconditioned warehouse far, far away.

How about this one allegedly from Fresno, California. Transcribed and somewhat translated. “Hi, Revis, is Roland from Lion Leash, I am a TV coordinator for Spotlight network, I am calling to extend an invitation for Emmy Award-winning director Logan Crawford would like to showcase your book. I am a TV coordinator. I’m reaching out regarding your book. Please call me back at 599-60….”

This one’s a favorite from Winfield, MO. “Hi, Ribs, my name is Johnester, and I’m calling for Ribs. (He was kinda making me hungry) Ribs Withem, and the reason I’m calling is I want to verify if you’re the author of The Texas Joe. If you are the author, please call me back at this number because your book caught our attention and I’d love the chance to speak with you shortly.”

Another from California. “Hi, Rellis, this is Paige senior executive book editor calling from Paige Chronicles, (I think that’s what she said. It’s hard to understand through all the crackling, which made me wonder if it’s coming through some transatlantic cable) because we would like to interview you about book scouts and specialist who highly recommended it from your feature to represent your book.”

“Hi, good day, this is Ava from Beach Chronicles a premium partner with Amazon once you have received this voicemail to call me back on thees number that works in order for us to discuss some important matters about your book The Broken Truth, a Thriller or thrillers (that’s not part of the title!!!). Thank you, and have a good one.”

*

And now I’m inundated with AI generated emails from Ellen B. Trumbull, or Christina William Brown, or Alison Malcha, Cecilia Marks II, and probably others, trying to separate me from my money. Here are a couple I cut and pasted, complete with the emojis they included.

Reavis,

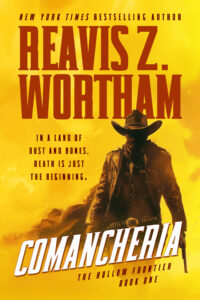

You’ve been called the “genuine article” by Craig Johnson, Kirkus compared your mysteries to Harper Lee and Joe Lansdale, and the New York Times praised your writing as a sleeper that deserves wider attention. You’ve penned Westerns, mysteries, and even 2,500+ articles. That’s one hell of a trail of words.

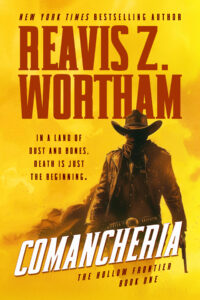

Now here comes The Only Saloon in Town bank robberies, scalp hunters, corrupt marshals, and Cap Whitlatch trying to keep the whole town from blowing sky-high. It’s cinematic, bloody, and gritty exactly what readers of Westerns crave.

But then I checked Amazon. 30 reviews. Thirty. (Note: I think there are more on that and Goodreads, but I don’t pay any attention to them.) That’s barely a bar fight in Angel Fire. A story with scalp hunters and marauding devils has fewer reviews than a $20 desk lamp. That’s just wrong.

I run a private community of 2,000+ dedicated readers who don’t just leave “Good book 👍” but dive in, analyze, and post thoughtful reviews that give books the credibility they deserve. They love supporting seasoned authors who already have a strong voice but need that extra boost of reader firepower.

So, Reavis should we let Cap Whitlatch keep drinking alone in a half-empty saloon of 30 reviews, or should we pack the place, light the lamps, and give this book the kind of attention even C.J. Box would raise a glass to? 🍺📖

Best,

I didn’t answer, so she tried again:

Hi Reavis,

Just circling back 30 reviews for The Only Saloon in Town doesn’t match the grit and firepower of your story. A book that is cinematic deserves a full house, not a half-empty saloon.

That’s exactly where my private community of 2,000+ engaged readers comes in. They love Westerns and mysteries, and they leave the kind of thoughtful reviews that boost credibility and visibility.

Would you like me to send you a quick 2-minute outline of how we can get Cap Whitlatch the packed saloon he deserves?

Best,

Then this one arrived. Same style, AI generated, and with still another hometown girl name (I wonder why they’re all women in these emails?).

Reavis, you’ve got gangsters rolling into East Texas, a crooked sheriff “crooked as a dog’s hind leg,” counterfeit bills floating around, a psychic kid dreaming doom, and a climax that reads like a Shakespearean showdown with cowboy boots on. Basically, Vengeance is Mine has more action than a Vegas card table on payday. 🎰💥

(Note: This one released in 2014. I’m not sure why they latched onto this particular title. Now, we continue.)

And yet… Amazon still thinks your book belongs in the quiet corner with dusty paperbacks and forgotten romance novellas. 182 reviews? For a modern western listed in True West’s Top 5? (At least AI got that part right) That’s like parking a Mustang on the prairie and calling it “just another horse.” 🐎😂

Here’s where I tip my hat. 🤠 I’m not a PR firm, not some slick “book marketing guru,” and I don’t have a website, LinkedIn, or a TikTok where I dance holding novels (you’re welcome). It’s just me and my private crew of 2,000+ readers who live for mysteries, thrillers, and western grit. We don’t skim and slap stars we actually read, argue about characters, and drop reviews that Amazon’s cranky algorithm can’t ignore.

So, Reavis, do you want Vengeance is Mine to keep sittin’ pretty in the shade like a cowboy at siesta, or do you want me to send in readers who’ll make it gallop loud enough for the whole algorithmic rodeo to notice? 🐂📚🔥

Best

I haven’t returned either of these emails, but they came in right on top of each other this week. Then I opened this one that’s cut and pasted.

Hi Reavis Wortham,

I hope this message finds you in great spirits.

My name is Allyson, and I’m reaching out on behalf of Books Discovery Group, a team of literary scouts and creative development agents passionate about discovering compelling stories with real market potential. While quietly evaluating promising works across the literary landscape, your book, “The Broken Truth: A Thriller (Tucker Snow Thrillers),” stood out for its powerful message, literary merit, and commercial viability.

We believe your manuscript (for crying out loud, people, it’s a book now, not a manuscript!!!) holds exceptional potential—not just for traditional publishing but also for adaptation into film or television. In today’s evolving storytelling ecosystem, producers are actively seeking fresh, impactful narratives like yours. With the right representation and positioning, your work could open doors to wide distribution and enduring cultural relevance across multiple platforms.

At Books Discovery Group, we work exclusively on a commission-based model, meaning we only succeed when you do. Our full focus is on securing the best possible publishing and screen adaptation opportunities for authors like you. You retain creative control—we handle the connections, negotiations, and positioning that help your work shine in competitive markets.

Before proceeding, may I ask if you are currently represented by another literary agent? If not, it would be an absolute honor to represent you and introduce your work to our trusted network of traditional publishers and media producers.

I’d welcome the opportunity to speak with you directly and explore what’s next. Please feel free to contact me at (347) 669-1975 at your convenience.

Thank you for creating a story worth discovering. I look forward to the possibility of working together and championing your book to a broader audience.

Warm regards,

When I didn’t answer, their algorithm tried again on, with a slightly different ending on The Broken Truth:

For The Broken Truth, a 10–20 reader push could seriously shake up its visibility and give Tucker the posse he deserves. I can even share a peek at how my readers discuss books you’ll see right away it’s real, passionate, and powerful.

What do you say want me to unleash a squad of die-hard thriller fans to ride with Tucker Snow and get this book seen by the readers it deserves? 🤠📚✨

Cecilia

*

So what is all this? Folks trying to drum up business? Author scams? I won’t say for sure, to avoid litigation, but I have my suspicions.

Scams targeting authors often involve an advance fee, where individuals or companies masquerading as agents or publishers request upfront payments for publishing or marketing services. Other scams include unrealistic royalties or a large book advance for a fee, claims of having “discovered” a previously unknown book, and requests for various fees to revitalize or market an older work.

Pros and beginners alike should be wary of these unsolicited offers, especially those promising huge returns, and avoid paying upfront fees for publishing services. Legitimate agents and publishers do not ask for such payments.

These people hoping to dig into your bank account might pose as a literary agent or publisher with misleading offers. They might contact you about an older book they just “discovered,” saying they can increase sales.

A new tact is claiming false affiliation with entities like Amazon, or a famous director they they might be able to put you in touch with. The Lionsgate scam with famous names has been making the rounds lately.

Be skeptical of unsolicited offers, never pay upfront fees, do your due diligence. If you think a call might be legit, find their website and use that number to check. They’ll likely tell you it was a con.

Research through The Authors Guild, or the Society of Authors to name a couple for alerts on scams targeting authors.

As Sonny and Cher once reported, “The Beat Goes On”….and on…and on…and on. I’m cynical, but many ground-level and even experienced authors can be taken by these scam artists. There are many online articles about these individuals, and more. Here are a couple that might be of interest. Writer Beware.

https://authorsguild.org/resource/publishing-scam-alerts/

https://writerbeware.blog/scam-archive/

Oh, and if any of the above contacts are truly legitimate, I’m sorry, and please reach out to me again so we can do the deal.