I just returned from Boucheron in New Orleans. The first time I was there in 1975, Mardis Gras was in full swing and most folks were juiced to the gills. I say most, because I only remember bits and pieces of that six-day trip. Today, people still drink there, heavily, and not just at night. As the sun lowers in the thick, humid air, neon still shines bright, reflected in puddles of fluids I don’t care to ponder.

But back to Bouchercon. This mystery thriller gathering of writers and fans is likely the largest in North America. There were panels, presentations, and lots of authors. Many of them drinking. Other than going out for meals (and they were all splendid) I spent most of the time in the bar, talking with other attendees, who may or may not have been partaking of spirits and club soda.

If you’ve never been to any writers conference, the bar is where business takes place. No matter if you drink or not, it’s like a Serengeti watering hole and almost everyone gathers there at one time or another in the evenings.

For some of us, it’s early afternoon.

Besides networking as we call it, I was on a panel along with four other excellent authors who shared their thoughts on “setting.” as a character. We’re all nice people, and everyone agreed that settings can become a character that can, and will, drive a story.

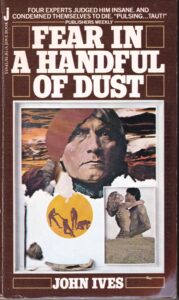

If you don’t think so, read Fear in a Handful of Dust by John Ives, the pseudonym of a prolific author, Brian Garfield.

I picked that title up back when it was released in 1978 and was blown away by Ives/Garfield’s gritty dialogue and the reality of people struggling to survive in the desert. The cast is limited to essentially five characters, an insane mental patient, and four doctors.

The sixth character is the Mojave Desert.

But that’s not what this blog is about…sorry.

It’s also not about making sure your microphone is turned off. One of the panelists almost said something that would have followed her for years. Remember. All mikes are hot, whether they’re turned on or not. And now, finally, back to my original subject.

During the course of our panel discussion that wandered nearly as much as this blog, fellow participants mentioned that in one of his own novels, a troll emerged at an earlier conference to bring up what that individual thought was an important mistake in let’s say, Mr. Smith’s novel.

“At one point in your latest work, you write that it rained on May 25, 1964. Well, that’s incorrect. I looked it up through Goggle, ChatGap, and an old man who siad he was there, but I’m not sure, because he’d been at a conference and couldn’t remember much about what happened, but the point is, through rabbit holes and research, I discovered that it in fact didn’t rain that day like you said. Did you realize that?”

Personally, I would have suggested that the troll kiss my…

However, Mr. Smith was shaken by that point. He shouldn’t have been.

He should have said in a loud, firm voice, “It’s fiction, you moron!!! Take it as entertainment and not nonfiction.”

So maybe Mr. Smith wanted it to rain that day in his book in order to accomplish some plot point, mood, or setting. Who’s to say a tiny little cloud didn’t pop up in Nebraska and drop an inch of rain in about an hour.

Case in point. Here in the Dallas/Ft. Worth metroplex, the National Weather Service office is at the DFW airport. That’s where records and airplanes are kept, but Texas is such a strange animal that it has rained at my house only thirty miles away while not a drop fell at the airport.

Therefore it was recorded as a rain-free day.

When I was a kid playing softball at my uncle’s house in the country, a cousin knocked a fly ball over the roof and into the front yard…where it was raining, though not a drop fell in the back yard. So we all ran around to the other side to get soaked, much to our mother’s pleasure.

And while I’m rambling around here on several subjects, let me point out to everyone that the thermometer at DFW is surrounded by concrete! It’s hotter there than at my house where we have trees and grass, so in my humble opinion (and that’s the only one that counts right this moment, in my opinion), the days when we reach that magic (gasp) number of 100 only counts in the middle of all that concrete!

Envision me shouting this fact like Sam Kinison.

So with that, please return to your writing. Be accurate with real places (one way vs. two-way streets for example), tell your fictional story (maybe change the name of your town so your streets can run the way you want them to), and don’t worry about the minutiae!!!

Pronounced muh-NOO-shee-ee, it refers to the small, precise, and often useless details or trifling matters of something, often in a literal sense.

Sam Kinison again, worrying about these things will only give you an ulcer!!!!