by James Scott Bell

Today’s post is brought to you by FIGHT CITY, the new Irish Jimmy Gallagher novelette. It’s Los Angeles, 1955, and all Jimmy Gallagher wants to do is meet his girl, Ruby, at the movies. But the City of Angels decides to put up its dukes and give Jimmy the fight of his life…

***

Back in the day, 25 years ago or so, when I was starting to pursue writing seriously, I wondered if it was possible to actually make a living at this thing. I know that was the dream of just about every scribe I came in contact with. The ideal was you could live anywhere, maybe on an island where they served piña coladas, and you would write during the day, eat your fill at night and, when needed, withdraw money from your ever-increasing bank account in the Caymans.

Or you could put your feet up on your desk or coffee table, stay in your pajamas if you wanted to, go unshaven for days at a time, and have publishers pay you large amounts because readers would want to buy your books the moment they hit the shelves.

Back then, you didn’t pay much attention to the statistics, which told you that the number of writers who managed to make more than $5000 a year was pretty small. You were going to be one of the exceptions!

When I finally did become a professional, I kept practicing law until I had a few years under my belt where the writing income was steady and growing. I phased out the law only when I had a track record and a multi-book contract in hand.

Thus, I have never been one to tell new writers they should hastily quit their day jobs. There is a lot to be said for a day job, as long as you don’t hate it so much that going to work feels like your soul is being sucked into the vacuum cleaner of dread.

But maybe not even then. The day job gives you reliable, steady income. It makes life predictable, financially speaking. It keeps you around people (writing full time is an isolating pursuit that sometimes makes you feel and act–and perhaps even look–like Ben Gunn from Treasure Island).

And if the job includes benefits, so much the better. Leaving all that for the uncertain life of a freelance writer is not a jump to be taken lightly. Ten years ago I would have advised a writer to have positive royalty income plus a multi-book contract before thinking of going it alone.

Of course, we are now in a new, self-publishing age. It is ever more possible to make serious money as a writer. Traditional publishing, undergoing its own uncertainties about the future, is no longer the only game in town–although it is still a game, and it is still in town.

So maybe you’re thinking of “the dream” for yourself. Here are some things you should ponder before taking the plunge.

1. Do you have the chops?

Let’s be blunt here. Most self-published material is not ready for prime time. In the “old days” (that is, before 2007), the arbiters of what was ready was a coterie of agents and acquisitions editors. To gain their approval, writers would grind their way through a learning process that included lots of words typed, craft studied, manuscripts critiqued (by friends, a group, or a professional freelance editor) and so on. Now, a writer can leapfrog all that and bounce straight into digital publication. But that may not be the right hop.

My advice: Find a way to replicate some of the traditional process before you publish. I’m a craft guy, as you know. In my early years I would try to identify my weak spots and then design self-study programs. Even when it wasn’t that intense, I’d be reading craft books and Writer’s Digest and novels I admired (to enjoy first then take apart). This should be ongoing for you. Since 1988 I don’t think a week has gone by when I did not do some active reading in or study of the techniques of writing fiction. If you’re just starting out to form your own library of craft books, I can suggest a place to begin.

Find a critique group of fellow writers you can exchange manuscripts with. Avoid toxic relationships, however.

Put together an actual proposal for your novel, even if you’re going to self-publish. Try to “sell” it to a friend or family member. This is a grinder, but it makes better writers.

2. Can you live with financial uncertainty?

As promising as self-publishing is, it is still a labor-intensive, up-and-down proposition. To help you live with the risk, I would counsel that you have a savings account with at least six months of living expenses in it. That cushion will soften any blows that come month-by-month.

Even when your flow becomes positive, you’re going to have to have the discipline to set aside money for estimated tax payments and unanticipated emergencies.

You will need to follow the advice of Mr. Micawber in David Copperfield: “Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen nineteen six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery.”

To be a full-time writer, learn to live below your means and sock the rest away: some for taxes, some for charity, some for retirement, some for investment, some in a liquid account.

Or marry a rich person.

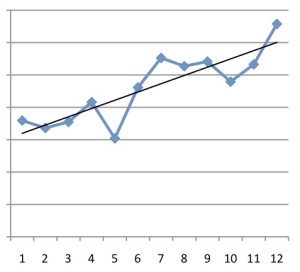

3. Does your self-publishing income show a year-long, upward trendline?

Unless and until you can produce new material on a regular basis, and show a steady increase in income over the course of a year (which is enough time to allow for fluctuations), I wouldn’t advise quitting your day job.

Further, your average monthly income at the end of the year should be hitting four figures. If you make under that much, but show a strong upward line, and know you can increase your output if you have more time to write, you might consider giving yourself a year of freedom from the day job to see what you can do. Everyone will have a different calculation about this. Commitments and financial needs will vary. If you are single and living in Tulsa or Fargo, your income needs will be less than if you are married and living in San Francisco or New York.

Make sure the people you care about most are okay with what you’re doing, unless it’s just your brother Arnold who thinks you’re crazy to be a writer anyway.

4. Can you operate a business?

This is going to be your job. You have to have a certain amount of business acumen to do it well. Some of my writer friends admit that they don’t have that kind of mind. For them, the day job or a working spouse is essential. They just want to write and hope for the best. That’s fine. There’s nothing wrong with that.

But the strategies for setting up a self-publishing business are not difficult to understand or implement. In fact, it’s little more than what you would have to do as an author for a traditional house. In the trad world you still have to market yourself which requires . . . strategies and discipline. You can put that same energy into setting up a self-publishing stream. You also now have a plethora of options, from doing it all yourself to going through a service (e.g., Smashwords, BookBaby) to choosing a bit of both.

5. What about health insurance?

A final factor is the benefit of health insurance. I have no idea what the Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”) is going to look like in 2014, when it really kicks in. Does anybody? But if it does one of the things it promises, it may mean that formerly uninsurable freelance writers (even with pre-existing conditions) can get health care coverage. (NOTE: What I’m looking for is practical information on what you think the ACA could mean for individuals. Let’s not get into a vitriolic debate about the act itself or its progenitor.)

So those are the thoughts out of the middle of my head. Let’s open it up for discussion. Do you dream of doing this writing thing full time? What advice would you give someone thinking about it?