“I have been writing for nineteen years and I have been successful probably because I have always realized that I knew nothing about writing, and have merely tried to tell an interesting story entertainingly.”

“I have been writing for nineteen years and I have been successful probably because I have always realized that I knew nothing about writing, and have merely tried to tell an interesting story entertainingly.”

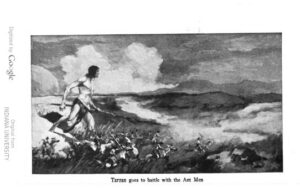

So wrote Edgar Rice Burroughs in an article for Writer’s Digest in 1930. The full text may be found here. I love the up-front honesty of the statement. It resonates with me because the first “real” book I read all the way through was Tarzan of the Apes. I still remember the feeling of being gripped by a story that wouldn’t let me go. When I finished, I knew I wanted to do the same thing someday.

I can even remember the precise moment I got pulled in so deep I put everything aside–playing outside, watching TV, riding my bike to the candy store–just so I could finish that book!

Allow me to share that moment with you.

Chapter One begins as a narrative frame, the voice telling us that he cannot vouch for the truthfulness of the tale, but what he is about to reveal is based upon the “yellow, mildewed pages of the diary of a man long dead.”

The man is John Clayton, Lord Greystoke. The text continues:

We know only that on a bright May morning in 1888, John, Lord Greystoke, and Lady Alice sailed from Dover on their way to Africa.

A month later they arrived at Freetown where they chartered a small sailing vessel, the Fuwalda, which was to bear them to their final destination.

And here John, Lord Greystoke, and Lady Alice, his wife, vanished from the eyes and from the knowledge of men.

I was hooked for sure. But the best was yet to come.

We are introduced to Black Michael, a mutineer, and I loved pirate stories as a boy. In Chapter Two, Black Michael takes over the ship and instead of killing the Claytons, as he was wont to do, he spares them because John Clayton had saved Black Michael’s life in Chapter One. Instead, the pirate sends Clayton and his pregnant wife to the jungle shore, where they will be on their own to survive!

was wont to do, he spares them because John Clayton had saved Black Michael’s life in Chapter One. Instead, the pirate sends Clayton and his pregnant wife to the jungle shore, where they will be on their own to survive!

But the best…not yet!

In Chapter Three the baby is born, a son, as John tries valiantly to make a safe home in the jungle for them, hoping against hope that a party from England will eventually find them.

Alas, it is not to be. Poor Alice dies. And the baby! The baby must still be nursed! The chapter ends with the last, sad journal entry of a man soon to be dead himself:

My little son is crying for nourishment—O Alice, Alice, what shall I do?

Great heavens! I was so into the story now. But there was more! I fell indelibly under the spell of Burroughs with the beginning of Chapter Four:

In the forest of the table-land a mile back from the ocean old Kerchak the Ape was on a rampage of rage among his people.

Wow!

The younger and lighter members of his tribe scampered to the higher branches of the great trees to escape his wrath; risking their lives upon branches that scarce supported their weight rather than face old Kerchak in one of his fits of uncontrolled anger.

The other males scattered in all directions, but not before the infuriated brute had felt the vertebra of one snap between his great, foaming jaws.

A luckless young female slipped from an insecure hold upon a high branch and came crashing to the ground almost at Kerchak’s feet.

With a wild scream he was upon her, tearing a great piece from her side with his mighty teeth, and striking her viciously upon her head and shoulders with a broken tree limb until her skull was crushed to a jelly.

And then he spied Kala, who, returning from a search for food with her young babe, was ignorant of the state of the mighty male’s temper until suddenly the shrill warnings of her fellows caused her to scamper madly for safety.

But Kerchak was close upon her, so close that he had almost grasped her ankle had she not made a furious leap far into space from one tree to another—a perilous chance which apes seldom if ever take, unless so closely pursued by danger that there is no alternative.

She made the leap successfully, but as she grasped the limb of the further tree the sudden jar loosened the hold of the tiny babe where it clung frantically to her neck, and she saw the little thing hurled, turning and twisting, to the ground thirty feet below.

With a low cry of dismay Kala rushed headlong to its side, thoughtless now of the danger from Kerchak; but when she gathered the wee, mangled form to her bosom life had left it.

Oh man! That was it! I was left hanging with a baby, all alone in the jungle, in the last chapter. Now I am completely into the story of…an ape! An ape who has lost her baby! And this villain named Kerchak. I wanted him to get his just desserts! I knew this poor ape Kala would find the Clayton baby and take him as her own. And that sooner or later, one or both of them would have to kill Kerchak in a duel to the death.

This was more than mere entertainment. This was magic. A story world unlike anything I’d ever seen, even when watching the Johnny Weissmuller Tarzan movies I loved so much.

Burroughs, no doubt, influenced generations of boys to become readers, authors, or perhaps flat-out adventurers. But when I mentioned the Burroughs quote at the top of this post to an online group of veteran writers, I was delighted by several women saying the John Carter and Tarzan books were favorites of theirs, too.

Which proves that great storytelling is great storytelling. That’s what we writers must aim for, every time we sit down and clack the keyboard. As Burroughs himself put it in that WD article:

“I have felt that it was a duty to those people who bought my books that I should give them the very best within me. I have no illusions as to the literary value of what I did give them, but I have the satisfaction of knowing that I gave them the best that my ability permitted.”

So what author carried you away like this when you were a kid?

Happy Father’s Day to all the dads out there. We have a rich history of movies about fathers, from King Vidor’s silent classic,The Crowd, to Judge Hardy (Lewis Stone) in the Andy Hardy series (keeping Mickey Rooney on the straight-and-narrow), to A River Runs Through It and Finding Nemo. So many others. Today I thought I’d share few favorite clips. Enjoy!

Happy Father’s Day to all the dads out there. We have a rich history of movies about fathers, from King Vidor’s silent classic,The Crowd, to Judge Hardy (Lewis Stone) in the Andy Hardy series (keeping Mickey Rooney on the straight-and-narrow), to A River Runs Through It and Finding Nemo. So many others. Today I thought I’d share few favorite clips. Enjoy!