by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

“Why do writers write? Because it isn’t there.” – Thomas Berger

So how can you get gas these days for under $4?

Eat at Taco Bell.

Ba-dump-bump.

And where do you get fuel for your writing? That’s today’s question.

Some of the ways are as follows.

Caffeine

Not everyone begins the day with a cup of joe, but it has been a mainstay of many a writer, starting with Balzac. He overdid it, of course. Drinking up to 50 cups of heavy-duty mud during his writing time, which was generally from 1 a.m. to 8 a.m., he produced nearly 200 novels and novellas before succumbing to caffeine-induced heart failure at the age of 51.

But the benefits of moderate coffee intake are now well known. It wasn’t always so. I was looking at a 1985 edition of the Los Angeles Herald Examiner, which had a headline about how a couple of cups of coffee posed a danger of developing heart disease.

Which reminds me of that scene in Woody Allen’s Sleeper, where a health-food store owner is cryogenically frozen in 1973 and wakes up 200 years later.

There he sees doctors smoking and talking about the benefits of tobacco, steak, and hot fudge.

“Those were once thought to be unhealthy,” a doctor explains. “Precisely the opposite of what we now know to be true.”

That’s coffee for you. In moderation, caffeine boosts alertness, powers up short-term memory, accelerates information processing, and increases learning capabilities.

I have a multi-published friend who favors diet, decaffeinated Coke. To which I say, “What’s the point?”

And to you I ask:

Do you have a favorite beverage to sip when you write?

There is also inner fuel that motivates writers.

Something to Say

There’s an old axiom in Hollywood: “If you want to send a message, use Western Union.” Meaning story comes first. A “message picture” can devolve into preachiness or propaganda if one is not careful.

Same for fiction. If you’ve got an issue you want to write about, go for it. But don’t let your characters become one-dimensional pawns in a hobbyhorse chess game.

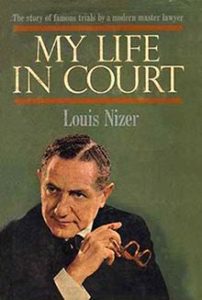

My advice is to give your hero a flaw, and your villain a justification. Remember, a villain doesn’t think he’s pure evil, except for this guy:

Write a “closing argument” for your villain, as if he’s arguing to a jury to justify everything he’s done. This is great psychological backstory, and you can drip some of it in. Believe me, this will make your villain more chilling and the reading experience more emotional, which is your goal.

Fun

Brother Gilstrap has said on more than one occasion that he is tickled he gets paid to “make stuff up.” That’s not a small matter. When you have joy in writing, it shows up on the page.

“In the great story-tellers, there is a sort of self-enjoyment in the exercise of the sense of narrative; and this, by sheer contagion, communicates enjoyment to the reader. Perhaps it may be called (by analogy with the familiar phrase, “the joy of living”) the joy of telling tales. The joy of telling tales which shines through Treasure Island is perhaps the main reason for the continued popularity of the story. The author is having such a good time in telling his tale that he gives us necessarily a good time in reading it.” – Clayton Meeker Hamilton, A Manual of the Art of Fiction (1919)

A Healthy Brain

Another reason to write is to fight cognitive decline. This has been mentioned here several times, by Sue and myself.

When you exercise your head through the rigors of writing a coherent and complex story, you keep it in fighting trim.

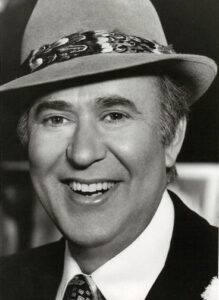

Last Friday was the 98th birthday of Mel Brooks. He and his partner, the late Carl Reiner (who died in 2020 at age 98) were trained in the Catskills style of improv comedy. Always on, always with the word play. At parties they started doing an improv skit about a 2000-year-old man, with Reiner as the interviewer. It got so popular they made a comedy album that became a huge hit, and they did their skit well into their 80s. Here’s a bit:

That’s why I’m skeptical of letting AI do your creative thinking. Every time it makes a decision for you is a time when your brain is lounging in a hammock, getting fat.

Money

Yes, some people write because they want to make money. It’s a hard gig for that, but if you treat it as a job and approach it like a business, you have a shot.

The old pulp writers knew this. They had to approach writing for the market like going to work each day, because they needed to put food on the table during the Depression.

But to do it, they had to know how to write stories that pleased readers. It’s a simple, capitalistic exchange: the product (a good story) sold to a customer (the reader) who is looking for a respite from the angst of the current moment.

“In a world that encompasses so much pain and fear and cruelty, it is noble to provide a few hours of escape, moments of delight and forgetfulness.” — Dean Koontz

Legacy

Mr. Steve Hooley has talked about writing for his grandchildren. My grandfather on my mother’s side was like that. He loved history, and wrote historical fiction that didn’t sell to publishers, so he published it himself for his family and friends.

He was especially interested in the Civil War. One of his stories was titled, “The Civil War Did Not Necessarily End at Appomattox.” Yeah, he need to work on his titles. But I’m glad to have the stories!

Without fuel, our writing is flaccid, uninspiring, boring. So I ask:

What fuels your writing?