by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

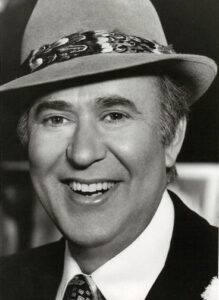

When Carl Reiner died recently at the age of 98, I pondered again my theory about comedians and their brains. It’s not scientific or scholarly or anything other than my personal observation, but it seems to me that comedians who daily exercise their brains by being funny, often on the spot, resist dementia as they age. Ditto trial lawyers.

I’ve written about this before:

What got me noticing this was watching Carl Reiner and Mel Brooks being interviewed together, riffing off each other. Reiner was 92 at the time, and Brooks a sprightly 88. They were both sharp, fast, funny. Which made me think of George Burns, who was cracking people up right up until he died at 100. (When he was 90, Burns was asked by an interviewer what his doctor thought of his cigar and martini habit. Burns replied, “My doctor died.”)

So why should this be? Obviously because comedians are constantly “on.” They’re calling upon their synapses to look for funny connections, word play, and so on. Bob Hope, Groucho Marx (who was only slowed down by a stroke), and many others fit this profile.

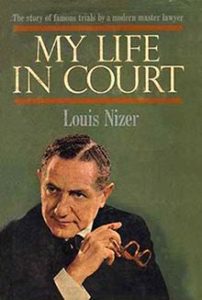

And I’ve known of several lawyers who were going to court in their 80s, still kicking the stuffing out of younger opponents. One of them was the legendary Louis Nizer, whom I got to watch try a case when he was 82. I knew about him because I’d read my dad’s copy of My Life in Court (which is better reading than many a legal thriller). Plus, Mr. Nizer had sent me a personal letter in response to one I sent him, asking him for advice on becoming a trial lawyer.

And there he was, coming to court each day with an assistant and boxes filled with exhibits and documents and other evidence. A trial lawyer has to keep a thousand things in mind—witness testimony, jury response, the Rules of Evidence (which have to be cited in a heartbeat when an objection is made), and so on. Might this explain the mental vitality of octogenarian barristers?

There also seems to be an oral component to my theory. Both comedians and trial lawyers have to be verbal and cogent on the spot. Maybe in addition to creativity time, you ought to get yourself into a good, substantive, face-to-face conversation on occasion. At the very least this will be the opposite of Twitter, which may be reason enough to do it.

In that post I offered a few creativity exercises to help writers keep the brain primed and playful. Today I want to add something else to the list.

I recently came across a scholarly article published a couple of years ago which demonstrated the effect that drawing has on memory.

We propose that drawing improves memory by promoting the integration of elaborative, pictorial, and motor codes, facilitating creation of a context-rich representation. Importantly, the simplicity of this strategy means it can be used by people with cognitive impairments to enhance memory, with preliminary findings suggesting measurable gains in performance in both normally aging individuals and patients with dementia.

So how might drawing operate as an aid to plotting your novel or scene?

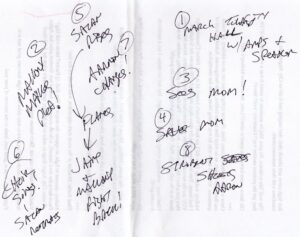

Most of you know about mind mapping. Early in my writing journey I read Writing the Natural Way, which teaches mind mapping as a practice for writers. I use it all the time. For example, I was trying to come up with a great big climax to one of my Mallory Caine, Zombie-at-Law novels. I took a walk to Starbucks, got a double espresso, and sat for awhile. Then I took out some paper and starting jotting ideas as they came to me. Here is that paper (the numbers I added later to give me the order of the scenes):

And that’s the ending that’s in the book.

When pre-plotting, I’ll take a yellow legal pad and turn it lengthwise and start mapping. Now I’m thinking about adding drawing to the mix. I don’t have to be a skilled cartoonist (good thing, for that is not one of the gifts bestowed upon me). But I can doodle, have a little fun, and trigger another part of my brain.

If you’re writing a scene with a closed environment, I can see value in making a map of the place—office, city block, house—and drawing the characters (even stick figures will do) as they negotiate the action. It might stimulate new ideas for the scene you wouldn’t get any other way.

Your friend, the brain. It is quite versatile indeed.

What about you? Do you use any visual techniques for your writing or creativity? (I’m on the road today and will check in when I can. Until then, talk amongst yourselves!)