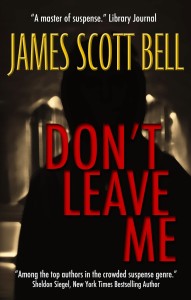

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

“I only write when I’m inspired, and I see to it that I’m inspired at nine o’clock every morning.” – Peter De Vries

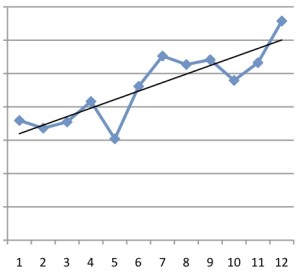

Anyone who’s written for any length of time knows there are times when the writing flows like the Colorado rapids. You whoop it up and enjoy the ride.

Sisyphus, Franz Stuck (1920)

Then there are times when it feels like you’re Sisyphus halfway up the mountain. You grunt and groan. But you keep pushing that boulder, because you know that writing as a vocation or career requires the consistent production of words.

What’s helped me in the Sisyphus times are writing quotes I’ve gathered over the years. I go to my file and read a few until I’m ready, as it were, to roll.

I’ve even contributed a couple of quotes that have found some purchase in cyberspace. The one that seems most widespread is this:

“Write like you’re in love. Edit like you’re in charge.”

There are, however, some writing quotes that are oft shared but were never said…or are misattributed. Two of them have been hung on Ernest Hemingway.

“Write drunk. Edit sober.” Nope, he never said that. Indeed, it would have horrified him. Hemingway was one of the most careful stylists who ever lived. He did his drinking after hours (and too much of it, as it turned out).

The other one is, “There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.”

It’s a great quote, but should be attributed to the legendary sports writer, Red Smith. Smith probably got the idea from the novelist Paul Gallico (author most famously of The Poseidon Adventure). This is from Gallico’s 1946 book Confessions of a Story Writer:

It is only when you open your veins and bleed onto the page a little that you establish contact with your reader.

(If you want to deep dive on the various attributions of the quote, go here.)

So how did this blood quote get attributed to Hemingway? I know the answer, for I am a skilled detective!

Actually, I am a Hemingway fan, so one day I decided to watch a TV movie about Hemingway and his third wife, Martha Gellhorn. The film, imaginatively titled Hemingway & Gellhorn, starred Clive Owen as Hemingway and Nicole Kidman as Gellhorn. As I recall, the movie is okay. But I do remember Owen delivering this line: “There’s nothing to writing, Gellhorn. All you do is sit at your typewriter and bleed.”

And there you have it. The script writers thought this quote, which they got from Red Smith, would be a perfect line for their rendition of Papa. And really, it might have been a line for him to utter, but for the fact that Hemingway did virtually all of his drafts in longhand.

Speaking of renditions of Hemingway on film, my favorite is Corey Stoll’s performance in Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris. Allen and Stoll managed to capture Hemingway’s bluster without turning him into a cartoon. I especially love this exchange with Owen Wilson, who is a laid-back writer from our time transported back to the Paris of the 1920s, where Hemingway, Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein and others were all tossed together.

Now, back to business. Here are five of my favorite writing quotes:

Remember, almost no writer had it easy when starting out. If they did, everyone would be a bestselling author. The ones who make it are the stubborn, persistent people who develop a thick skin, defy the rejection, and keep the material out there. – Barnaby Conrad

You must stay drunk on writing so reality cannot destroy you. – Ray Bradbury

In a world that encompasses so much pain and fear and cruelty, it is noble to provide a few hours of escape, moments of delight and forgetfulness. – Dean Koontz

Keep working. Keep trying. Keep believing. You still might not make it, but at least you gave it your best shot. If you don’t have calluses on your soul, this isn’t for you. Take up knitting instead. – David Eddings

The first page of a book sells that book. The last page sells your next book. – Mickey Spillane

Your turn! Let’s get inspired. Share a favorite writing quote and why it speaks to you.