by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

I have been musing about something of late. Call it a typology of writers. Here the categories I’ve come up with, recognizing there will be some overlap. Let’s discuss.

1. Nothing But Fun

There are some writers who believe writing fiction should be nothing but a joy, carefree, never a matter of sweat or concern. Under this category, there are two sub types. The first believes that a carefree first draft is the only draft it should be written. Cleaned up a bit for typos, perhaps, but left mostly alone. The other subtype writes that first draft and then looks at it and wonders what the heck to do with it, and tries to apply some actual craft and editing.

2. Hate Writing, But Love Having Written

I know a few colleagues who fit this category. They find writing a first draft to be a somewhat difficult trudge. Sometimes this is because their standards go up with each book. The bar is raised. And they seriously want to meet that challenge.

But when they are done with the whole process, including editing and polishing, and the book is the better for it, they find tremendous satisfaction.

3. Lunchpail Type

This is a writer who goes to work each day. They’re not looking for a rapturous experience, though that may happen when they’re not looking. They set out to write a certain number of words each day and do that job. They know their craft and care about it, because they want to sell to readers, and readers care about good stories. The great pulp writers of old were like this. They could type 1 million words a year, sometimes more, and sell their product for a penny or two per word.

4. Doesn’t Care About Sales

In truth, I think every writer cares about sales. Who wouldn’t appreciate a little green from what they write? There’s that famous Samuel Johnson quote: “No man but a blockhead ever wrote except for money.” But this type of writer rejects that notion and finds their satisfaction in writing alone. Nothing wrong with that. Writing can be a form of enjoyment, diversion, mental exercise, or escape.

5. Only Cares About Sales

Finally, there is the writer who is in this strictly for the money. There’s never been anything illegal about that. If somebody write something and there’s a market for it, that’s a fair exchange. But these days it’s possible to make money producing acres of “AI slop.” We all wish this weren’t true, but it is. This type shouldn’t even be categorized as a “writer.”

On the other hand, someone who sees writing as a way to make money, or at least side-hustle dough, and works to figure out how to write a good product, fine. I suspect this is the least populated category.

In reviewing this list, I would put myself as a #3. I’ve always written to a quota. I have also found tremendous satisfaction in learning my craft and getting better at it.

So what do you think about the above categories? Would you add one? Modify one? Where would you place yourself?

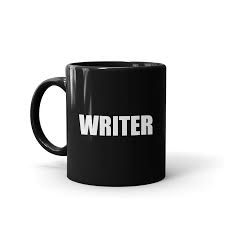

First thing I did when I decided to become a writer (even if I couldn’t learn like they told me in college, even if I failed) was go to a bookstore and buy a black coffee mug with WRITER on it. I wanted to look at it every day, and believe it. I don’t think I ever drank coffee from it. It’s still here in my office. I still look at it every day.

First thing I did when I decided to become a writer (even if I couldn’t learn like they told me in college, even if I failed) was go to a bookstore and buy a black coffee mug with WRITER on it. I wanted to look at it every day, and believe it. I don’t think I ever drank coffee from it. It’s still here in my office. I still look at it every day.

We had a good discussion recently about

We had a good discussion recently about  James N. Frey, author of the popular craft books

James N. Frey, author of the popular craft books