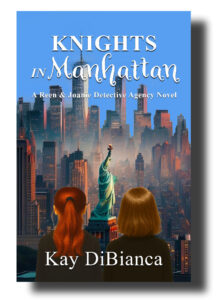

Dear crime dogs. Due to an unexpected family emergency, I am en route today to New Jersey. Not sure when I will be back or when I will have extra time. Didn’t have time to finish my planned post on anti-heroes. Will save my notes for my next round. So forgive me today for re-posting an old topic dear to my heart. Will try to weigh in during layover in Chicago. Thanks for your patience!

By PJ Parrish

“Talent is insignificant. I know a lot of talented ruins. Beyond talent lie all the usual words: discipline, love, luck, but most of all, endurance.”–James Baldwin

I wanted to be a ballet dancer. This was way back in grade school, when I was as round as a beachball and rather lost. So I bugged my dad until he let me enroll in Miss Trudy’s School of Dance and Baton Twirling.

Did I mention I was chubby? Did I mention I had no talent? Neither stopped me. I had a ball trying and to this day, I can remember every step of my first recital dance. I eventually lost the weight but never the desire to dance. So around age 30, I took up lessons again. I did pretty good. Until I got to pointe. You know, the part where you shoe-horn your feet into those pretty pink satin shoes with a hard box at end and then you’re supposed to just rise up on your toes?

It hurts like hell.

So I gave up. Did I mention I had no talent?

Flash forward. I became a dance critic. Those who can, do. Those who can’t, well…

I got to meet and interview almost every famous dancer of my era, including Barshnikov, Margot Fonteyn, Bob Fosse, you name it, I also got to cover the birth of the Miami City Ballet, and became friends with the artistic director the late Edward Villella. One day, he asked me if I wanted to be in The Nutcracker. In the first act party scene where the parents do a little minuet-type of dance. I accepted. So I danced, in front of 5,400 people. I didn’t screw up. It was one of the most memorable nights of my life. To quote one of my favorite writers, Emily Dickinson:

I cannot dance upon my Toes—

No Man instructed me—

But oftentimes, among my mind,

A Glee possesseth me,

This is my round-about way of getting to my topic — talent vs technique. See, I had the desire, but I didn’t have the body type, the turn-out of the hip joints. I knew the steps, sure, but I didn’t have that vital muscle memory that comes to all dancers after years and years of learning their craft. I didn’t have the music inside me that separates the mere dancer from the artist.

So it is, I believe, with writers.

Years ago, my friend Reed Farrel Coleman wrote an article in Crime Spree Magazine titled “The Unspoken Word.” It was about his experience as an author-panelist at a writers conference. Reed was upset because he thought the conference emphasized technique to the exclusion of talent.

Reed wrote: “To listen how successful writing was presented [at the SleuthFest conference], one might be led to believe that it was like building a model of a car or a jet plane. It was as if hopeful writers were being told that if everyone had the parts, the decals, the glue, the proper lighting, etc. to build this beautiful model and then all they needed was the instruction manual. Nonsense! Craft can get you pretty damned far, but you have to have talent, too. Writing is no more like building a model than throwing a slider or composing a song.”

At the time, I was the president of the Florida chapter of Mystery Writers of America, and our board decided, after much debate, to purposely steer SleuthFest toward the writers “workshop” conference. We did it because attendees told us they didn’t want any more authors getting up there just flapping their gums telling tired war stories. They wanted authors to pull back the green curtain and show how it is done. They wanted to hear authors talk about how they created memorable characters, how they maintained suspense, how they built a structure, why they chose a particular sub-genre. That’s what we gave them.

You know, sort of what we try to do where at The Kill Zone.

But Reed did raise an interesting question in his article — can novel writing really be taught? I think it can and should be. I think unpublished folks can go to workshops, read books, and learn the basics about plotting, character development, the arc of suspense, the constructs of good dialog.

Does that mean they have the stuff they need to be a successful writer? No, it only means they might — if they work hard — have a chance of mastering their craft. And I don’t care how talented you are, you aren’t going anywhere without craft.

Let’s go to the easy metaphor here — sports. A person may be born with a natural ability for basketball. They may be tall, able to shoot hoops with accuracy and be a fast runner. But that’s not enough. There was this guy who played for the Chicago Bulls…I forget his name. He didn’t make his high school’s varsity basketball team until his junior year, and when he got to University of North Carolina, he told the coach he wanted to be the best ever. Yeah, he had talent. But he worked like a dog. He became the best.

When I teach writing workshops, I preface everything with this one statement: I can teach you the elements of craft but I can’t teach you talent. Anyone can learn to hit a baseball. But only a few are going to have Ted Williams’ eye. The rest are going to be the John Oleruds of the world — competent major league role players. And what’s wrong with that if you can at least get to The Bigs, have a healthy backlist and maybe take the kids to Disney World on your royalties?

Which brings me back to James Baldwin’s quote. There are, indeed, many “talented ruins” out there. And there are many not-so-talented writers making a good living from their books. Some even become bestsellers.

So where to I come down on the talent question? I agree with Reed. All good writers have some talent. But I also believe you can’t have talent without craft and desire. Peter Benchley once said: “It took me fifteen years to discover I had no talent for writing, but I couldn’t give it up because by that time I was too famous.” True, Jaws is a little cheesy, but it was one of the greatest serial killer thrillers ever imagined.

Most people are familiar with “fight or flight” response to a threat. Physiologist and Harvard Medical School chair,

Most people are familiar with “fight or flight” response to a threat. Physiologist and Harvard Medical School chair,