What leads you down the rabbit hole when writing or planning your book?

How do you get out?

Crime doesn’t pay, so they say. Well, whoever “they” are, they aren’t in touch with today’s entertainment market because crime—true and fiction—in books, television, film, or net-streaming, is a highly popular commodity. One solid crime writing sub-genre, detective fiction, is hot as a Mexican’s lunch.

Detective fiction has been hot for a long, long time. Crime writing historians give Edgar Allan Poe credit for siring the first modern detective story. Back in 1841, Poe penned Murders In The Rue Morgue (set in Paris), and it was a smash hit in Graham’s Magazine. Poe’s detective, C. Auguste Dupin, used an investigation style called “ratiocination” which means a process of exact thinking.

Poe’s style brought on the cozy mysteries, aka The Golden Era of Crime Fiction of the 1920s. Detectives like Sherlock Holmes and Miss Marple solved locked-room crimes. They intrigued readers but spared them gruesome details like extreme violence, hardcore sex, and graphic killings.

The golden crime-fiction genre evolved into the hardboiled detective fiction movement, circa 1930s-1950s. Crime writers like Dashiell Hammett gave us the Continental Op and Sam Spade. Raymond Chandler brought Philip Marlowe to life. Carroll John Daly convincingly conceived Race Williams. And Mickey Spillane, bless his multi-million-selling soul, left Mike Hammer as his legacy.

The ’60s to 2000s gave more great detective fiction stories. Anyone heard of Elmore Leonard? How about Sarah Paretsky and Sue Grafton? Or, in current times, Michael Connelly, Megan Abbott, and a wildcard in the hardboiled and noir department, Christa Faust?

These storytellers broke ground that’s still being tilled by great fictional detectives. Television gave us Perry Mason, Ironside, Columbo, Jack Friday, Kojack, and Magnum. Murder She Wrote? How cool was mystery writer and amateur detective Jessica Fletcher? And let’s not even get into big screen and the now runaway net-stream stuff.

So why the unending popularity of detective fiction? I asked myself this question to understand and appreciate the detective fiction part of the crime story genre. I worked as a real detective for decades, and I know what it’s like to stare down a barrel and scrape up a cold one. But once I reinvented myself as a crime writer, I had to learn a new trade.

I’m on an even-newer venture right now, and that’s developing a net-streaming style series. It’s a different—but not too different—delve into hardboiled detective fiction, and the series is titled City Of Danger. To write this credibly, and with honor to heritage, I’ve plunged into a rabbit hole of research that’s becoming more like a badger den or a viper pit.

I’m on an even-newer venture right now, and that’s developing a net-streaming style series. It’s a different—but not too different—delve into hardboiled detective fiction, and the series is titled City Of Danger. To write this credibly, and with honor to heritage, I’ve plunged into a rabbit hole of research that’s becoming more like a badger den or a viper pit.

What I’m doing, as we “speak”, is learning this sub-genre of crime writing—hardboiled detective fiction—and I’ve learned two things. One, I found out I knew SFA almost nothing about this fascinating fictional world that’s entertained many millions of detective fiction fans for well over a hundred years. Two, detective fiction has far from gone away.

My take? Detective fiction—hardboiled, softboiled, over-easy, scrambled, or baked in a cake—is on the rise and will continue being a huge crime-paying moneymaker in coming years. There are reasons for that, why detective fiction remains so popular, and I think I’ve found some.

I stumbled on an interesting article at a site called Beemgee.com. Its title Why is Crime Fiction So Popular? caught my attention, so I copied and pasted it onto a Word.doc and dissected it. Here’s the nuts, bolts, and screws of what it says.

Crime fascinates people, and detectives (for the most part) work on solving crimes. But the crime genre popularity has little to do with the crime, per se. It has far more to do with the very essence of storytelling—people are hardwired to listen to stories, especially crime stories.

Detective fiction is premiere crime storytelling and clearly exhibits one of the fundamental rules of storytelling: cause and effect. In detective fiction, every scene must be justified—each plot event must have a raison d’etre within the story because the reader perceives every scene as the potential cause of a forthcoming effect.

Picture a Roman arch bridge. Every stone is held in place by its neighbor just like story archs with properly set scenes. Take away one scene that doesn’t support the story arch and the structure fails.

Picture a Roman arch bridge. Every stone is held in place by its neighbor just like story archs with properly set scenes. Take away one scene that doesn’t support the story arch and the structure fails.

Well-written detective fiction has a bridge-like structure. Each scene in the storytelling trip has some sort of a cause that creates an effect. This subliminal action keeps readers turning pages.

The article drills into detective fiction cause and effect. It rightly says the universe has a law of cause and effect but we, as humans, can’t really see it in action. But we’re programmed to know it exists, so we naturally seek an agency—the active cause of any actions we perceive.

Detective fiction stories, like most storytelling types, provide a safety mechanism. A detective story is built around solving a crime by following clues. A cause. An effect. A cause. An effect. The story goes on until you find out whodunit and a well-told story leaves you with a satisfying end where you’ve picked up a take-away safety tip.

But detective fiction stories aren’t truly about whodunit. Sure, we want the crook caught and due justice served. However, we want to know something more. We want to know motive, and this is where the best detective fiction stories shine. They’re whydunnits.

Whydunnits are irresistible stories. They’re the search for truth, and in searching for truth in detective fiction storytelling—why this crime writing sub-genre remains so popular—I found another online article. Its title Why Is Detective Fiction So Popular? also caught my attention.

Cristelle Comby

This short piece is on a blog by Swiss crime writer, Cristelle Comby. If you haven’t heard of Cristelle, I recommend you check her out. Her post has a quote that sums up why detective fiction is so popular, and it’s far more eloquent than anything I can write. Here’s a snippet:

“Detective novels do not demand emotional or intellectual involvement; they do not arouse one’s political opinions or exhaust one by its philosophical queries which may lead the reader towards self-analysis and exploration. They, at best, require a sense of vicarious participation and this is easy to give. Most readers identify themselves with the hero and share his adventures and sense of discovery.

The concept of a hero in a detective story is different from that of a hero in any other kind of fictional work. A hero in a novel is the protagonist; things happen to him. His character grows or develops and it is his relationship to others which is important. In a detective story, there is no place for a hero of this kind. The person who is important is the detective and it is the way he fits the pieces of the puzzle together which arouses interest. Thus in a detective story it is the narration and the events which are overwhelmingly important, the growth of character is immaterial. What the detective story has to offer is suspense. It satisfies the most primitive element responsible for the development of story-telling, the element of curiosity, the desire to know why and how.

Detective stories offer suspense, a sense of vicarious satisfaction, and they also offer escape from the fears and worries and the stress and strain of everyday life. Many people who would rather stay away from intellectually ‘heavy’ books find it hard to resist these. Detective fiction is so popular because the story moves with speed.”

As a former detective, and now someone who writes this stuff, I think detective fiction is so popular because readers can safely escape into a dark & dangerous world of wild causes and wild effects—full of fast-reading suspense—and they get powerful insight into what makes other people (like good guys and bad girls) tick. Detective fiction is crime that has paid, does pay, and always will pay. It’s just that popular.

Kill Zone readers and writers: If you’re into detective fiction, what do you think makes it popular? And if you’re not into the genre, what makes you dislike it? Don’t be shy about commenting one way or another!

——

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective and coroner with over thirty years experience in human death investigation. Now, Garry has reinvented himself as a crime writer with his latest venture into a hardboiled detective fiction series called City Of Danger. Here’s the logline:

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective and coroner with over thirty years experience in human death investigation. Now, Garry has reinvented himself as a crime writer with his latest venture into a hardboiled detective fiction series called City Of Danger. Here’s the logline:

A modern city in dystopian crisis enlists two private detectives from its utopian past to dispense street justice and restore social order.

Follow Garry Rodgers on Twitter and visit his website at DyingWords.net.

A couple of weeks ago, Brother Bell posted Advice For the Demoralized Writer, and I confess it cut a bit close to the bone. I was the beneficiary of the crazy advances of the 1990s. The combined advances for my first two books (Nathan’s Run and At All Costs) weighed in at about $4 million, including the movies that were never made. For Books 3 & 4, the advances totaled about $150,000. None of them earned out.

I couldn’t give away Book #5. My career was declared dead, even though each of those books achieved critical acclaim and won some awards. Was it hard on the ego? Darn tootin’ it was. Mostly, it was embarrassing. My books and I were featured in People Magazine, Entertainment Weekly, Publisher’s Weekly, Larry King’s radio program and Liz Smith’s Hollywood column. Heady stuff for a safety engineer in Woodbridge, Virginia.

A huge share of the publicity surrounding the books focused on the eye-popping numbers. I had nothing to do with that publicity, of course, but imagine the angst and anger of journeyman authors who hadn’t earned nearly that kind of scratch over the entirety of their prolific careers. To this day, there is one household-name author who was famous then and still pretty famous today who will not speak to me. He never has. Not once.

When the books didn’t come close to earning out, the entire industry knew it, and more than a few of my fellow authors smirked through their expressions of sympathy and support. I got it then, I get it now. The most common advice I got was to write under pseudonym. Looking back, I believe that they believed that they were helping me deal with my loss.

Except, I hadn’t lost. Never thought I had.

Lessons From Safety Engineering.

At the time, a good bit of my Big Boy Job involved accident investigations. The nature of “energetic incidents” (aka unexpected explosions) is such that the hardware involved ends up looking little like it did before it blew up. Thus, most investigations started with what was left–what went right.

In the case of my mourned writing career, I knew that I could tell a good story that people enjoyed reading. I knew from fan mail that my characters were three-dimensional, and I knew from previous contracts that industry professionals thought I had potential.

I also was awash in empirical data that publishers were unwilling to roll the dice on my brand of family-focused dramatic thrillers. That doesn’t reflect the quality of the writing or the stories, but merely risk-based business analysis. As with every industry, bean counters make the final decisions.

I knew what worked and what didn’t, and I knew that I was going to make this writing gig work.

That’s worth repeating. I was going to make this writing gig work. Hard stop.

Now I had to engineer the way to do that.

Wise Advice From A Friend.

I’ve known Jeffery Deaver for many years–long before he became Jeffery Friggin’ Deaver, mega-selling author. For the better part of a decade, we had a standing date at a local bar every Thursday for dinner and drinks. (Now it’s virtual and we’ve moved it to every Wednesday.) I’d hit bottom just about the time when The Bone Collector was making him a household name, and I asked him one evening, “What are you doing right that I’m doing wrong?”

He answered without pause, “Last time I counted, I was sixteen books ahead of you.”

Yeah, okay. Fine. Perspective.

Then he went on to say, “You know you have to keep writing. Stopping isn’t an option.”

“What if I can’t sell anything?” I whined.

“Nobody says you have to do it fulltime.”

That one rocked me back. Money wasn’t the issue, but self esteem was. I realized that as wonderful and exciting as the publishing biz is, it’s fundamentally the entertainment business, and there is no more capricious industry in the world. When you look at the decisions they make–and the ones they don’t–you’d think that they threw darts at the wall.

I realized that I wasn’t suited to that, certainly not as my fulltime focus. I’m an engineer at heart. In 2004, I went back to a high-profile Big Boy Job and became a more prolific writer than ever before. (More on that below.)

Writers Write.

Here’s where I have to confess that serendipity plays a role in all our lives. The trick is to recognize a break when it arrives and to determine what to do with it.

Thanks to A Perfect Storm and Black Hawk Down, narrative nonfiction was taking off in the late nineties and early aughts. That was when I met Kurt Muse, a U.S. citizen imprisoned by Manuel Noriega and ultimately rescued by Delta Force. His story thrilled me. We agreed to collaborate on what became Six Minutes To Freedom, the book that I am probably most proud of. It’s nonfiction and a kick-ass thriller. (Serendipity again: As I write this, SixMin is on sale for $1.99 on Amazon.)

My agent at the time refused to present SixMin to publishers because of bullshit political bigotry so I fired her and took on the lovely and talented Anne Hawkins as my agent. Her first task was to tell me that no publishers wanted SixMin because I was not a journalist, and only journalists can write narrative nonfiction.

Once more, pardon my language. Bullshit.

Way back in the early days after Nathan’s Run had hit the shelves, I met a fellow named Steve Zacharius, who at the time was an executive with Kensington Publishing in New York, and he was a huge fan of my writing. His words to me were something to the effect of, “if you ever find yourself in need of a publisher, let me know.”

I let him know, and he bought the book–for very little money. I would share the number if it were not for the fact that Kurt is part of the deal, and that wouldn’t be right, under the circumstances.

Six Minutes To Freedom hit the stands in 2006. It didn’t do much business in stateside brick and mortar stores, but it caught fire on U.S military facilities around the world. That was a time when tens of thousands of military personnel were in harm’s way and needed stories of heroes and successful military operations. The book earned out its advance in three weeks. Twenty or so members of the U.S. Army’s First Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta (“Delta Force”) attended the book party at my house. Among them were the delightful, funny and kind models for characters later to be named Jonathan Grave and Boxers.

The presumed corpse of my career took a giant breath. Its heart light started to glow again.

Nothing breeds success like success. I pitched the Jonathan Grave series to Kensington, and they took it on. Thirteen series books later, I am happy to report than every one of them has earned out its advance in the first year. When the rights to Nathan’s Run and At All Costs reverted to me, Kensington snapped them up. Remember that fifth novel I couldn’t give away? They bought that, too. It came out as Nick Of Time.

Books are products, and products trend.

Even though the sales figures for the Grave series trend up each year, I know (fear?) that every boom is counterbalanced by a bust. That’s why, when I was smacked with the idea of a cool post-apocalyptic tale, I pitched my Victoria Emerson series and signed a contract for Crimson Phoenix and Blue Fire (2022).

I’ve got a great idea for an occult detective series, too, but that one needs more development. Ditto my paradigm-changing Christmas series.

Failure cannot be inflicted.

I’ve made this point here before, but it bears repeating: When it comes to writing and publishing, ain’t none of us are victims. We are part of an industry that is desperate for new material, even if executives are not entirely sure what they’re looking for. Our job is to be different, exciting and persistent.

A couple of Sundays ago, when Brother Bell presented the story of the composite writer whose life was derailed and he turned to drink, I felt little sympathy. If a person chooses to quit any profession, he needs to be prepared to live with the consequences. If a publisher drops your books, you’ve been presented with a crossroads. You can choose to quit, or you can choose to adjust, but no one can force you to do either one. Most of the successful authors I know have been slapped around by the business. They’re successful because they stayed with it.

It doesn’t matter that others think that you’re out of the game. As long as you don’t give up, you’re still in the fight.

On the day you quit, understand that you will have declared your failure. No one will have inflicted it on you.

By PJ Parrish

Good morning, folks. Hope your long weekend was spent with family and friends and connections were reborn. I’m up in Michigan now for half the year and it has been wonderful seeing family again. It’s great to get hugs and go out for a hamburger. But now it’s time to get back to work, so on this Tuesday, I offer up a First Pager from one of our contributors. Give it a read and we’ll talk.

Girl in the Leaves

“How are you feeling today, Rebecca?” Dr. Ashley Riley asked, seated behind a large pine desk. “It’s been eleven months since our last session.” She walked from around the desk, took a seat in the leather chair across from me and placed a recording device on the table separating the two of us. Doctor Riley was a lean, bright-eyed woman in her mid-fifties.

Her long, chestnut hair had been pulled into a ponytail.

My eyes burned from lack of sleep. “Peachy-keen, Doc.”

“Nice try. Now tell me the truth.”

This woman had always been direct—a quality I both liked and disliked about her. Soft music played in the background. A large flat screen television displayed a fireplace, its flames moving in harmony with the melody. I never understood the benefit of listening to the sounds of sitar music, but never enough to ask to stop it.

My right knee trembled. I thought about sipping the iced coffee but decided against it. I have a ruby birthstone where my wedding band used to be. Sometimes, like now, when I’m nervous I twist it around my finger.

“I’ve been having dreams. Nightmares would be more accurate.”

“What kind of nightmares?”

“My mother getting away with murder.”

She stared at me. “The trial date been scheduled?”

“No. And that’s disconcerting.”

“How long has she been awaiting trial?”

“Eighteen months and counting.”

Doctor Riley pursed her lips, taking in the information. She never responded too quickly. I wondered if this was a skill taught by her professors at school or honed over time. “In the grand scheme of things, eighteen months for a high-profile case is not uncommon. As a homicide detective, you know this. So why don’t you tell me what’s eating at you.”

I stood. My legs went all rubbery and for a moment I worried they might give out. They didn’t and I walked over to an aquarium. A variety of marine life called this home. My favorite was the Oscar who seemed to rule the tank. As a child my father, my biological one not the animal who molested me, bought me a fishbowl when I turned six. He helped pick out a Beta. But after my father’s death, I could never bring myself to own another fish tank.

_____________________

There’s a lot I like about this beginning, so most my thoughts, dear writer, are focused on subtle ways to perhaps refine what is already here. Although the opening is not action-packed, it has a good quiet tension about it that would make me want to read on. I’ve read a lot of these kind of openings in recent years — a troubled protagonist is in a doctor’s office and the doctor’s questioning is our portal into the plot. It’s a common trope now, so there’s a chance this can feel stagey and trite. I’ll let you all weigh in on that, but I’m willing to give the writer some time to develop Rebecca’s story a bit more.

I like that the writer is conveying necessary backstory info via dialogue rather than merely relying on narrative. (She/he is using both here). For example, the writer could have written something like this:

I had been having nightmares for months now and they were always the same — some variation that my mother, who had killed my father, had broken out of prison and was now coming for me. The thing was, I didn’t even know where my mother was and the trial wasn’t scheduled for another eighteen months. But I still was plagued by bad dreams.

(I took some plot liberties to make a point.) What’s wrong with this? Eh, it’s all narrative and while it’s okay, it’s much more compelling to dole out this info via dialogue, as our writer does. Always remember: DIALOGUE IS ACTION. So kudos writer! Yes, it’s okay to move into pure narrative at times, as this writer does with this:

As a child my father, my biological one not the animal who molested me, bought me a fishbowl when I turned six. He helped pick out a Beta. But after my father’s death, I could never bring myself to own another fish tank.

The revelation about the mother comes via dialogue, so I like the change-up when the writer switches to narrative/memory for the father backstory. It’s all about controlling your pacing and giving the reader variety. Narrative = slowing down. Action/Dialogue = speeding up and immediacy. So use each wisely when it comes to pacing.

Now, let’s talk about the opening graph. I’m not crazy about it. If you open with a quote, especially from the non-protagonist, it darn well better be a good one. “How are you feeling today?” just doesn’t rock my boat. It has no resonance, no juicy hidden meaning. With the rest of the scene being so good, I’d like the writer to try to find something less banal. Now the NEXT line, wherein the doc tells us Rebecca’s been AWOL from her therapy for nearly a year IS interesting. And I would think that this fact is foremost in the doctor’s mind. Weigh in if you disagree!

Also, I think we have a problem with focus here. The doctor gets the first line, the first full name, and the first physical action. Which takes our focus OFF Rebecca at the very time when we need to establish a connection with her. We need the reader’s full attention on Rebecca. Even if the writer choses to give the doctor the first line, I’d take her name and physical movement out of the equation. This is easily fixed, something like:

“You’ve been away a long time, Rebecca. What happened?”

I stared at the woman across the desk from me, trying to figure out how to answer. Dr. Ashley Riley was a lean, bright-eyed woman in her mid-fifties. The last time I had seen her, her chestnut hair had been short, but now she was wearing it in a ponytail. I realized I couldn’t remember how long ago our last session had been — six months, a year?

How the doc wears her hair is not important — unless you MAKE it mean or relate something, in this case, Rebecca’s absence. Description needs to have purpose. Don’t lavish description and dialogue on secondary characters at the expense of your protagonist. (especially in first person POV).

Now, let’s do a quick line edit.

“How are you feeling today, Rebecca?” Dr. Ashley Riley asked, seated behind a large pine desk. “It’s been eleven months since our last session.” She walked from around the desk, took a seat in the leather chair across from me and placed a recording device on the table separating the two of us. Doctor Riley was a lean, bright-eyed woman in her mid-fifties. This is what I mean by wasting description on a secondary character, which created a false-focus in the reader’s mind. Ditto the detail about the ponytail below.

A note about the doctor placing a “recording device” on the desk. I asked a psychiatrist friend about this and she said that sessions are not routinely recorded and that most doctors just take notes. If recordings are needed, they must be with the consent of the patient to be legal. So the writer has to eliminate this or clarify it.

Her long, chestnut hair had been pulled into a ponytail.

My eyes burned from lack of sleep. Nice detail. “Peachy-keen, Doc.”

“Nice try. Now tell me the truth.” Dialogue is brisk and note lack of attribution. Not needed!

This woman had always been direct—a quality I both liked and disliked about her. Might be a good place to drop in backstory: How long has she been seeing this doc? Soft sitar music played in the background. A large flat screen television displayed a fireplace, its flames moving in harmony with the melody. I never understood the benefit of listening to the sounds of sitar music, but never enough to ask to stop it. Something missing here. “but was never brave enough…?

My right knee trembled. I thought about sipping the iced coffee where did it come from? but decided against it. I have a ruby birthstone where my wedding band used to be. Nice way to slip in backstory! Sometimes, like now, when I’m nervous I twist it around my finger.

“I’ve been having dreams. Nightmares would be more accurate.”

“What kind of nightmares?”

“My mother getting away with murder.” Well, this makes me want to read more, as does the next exchange. Mom’s up on a “high profile case” maybe a murder charge? But apparently, she’s out on bail? Unclear. Also, IF indeed mom is up for murder, she can’t get bail pending trial. (Very rare exceptions). Check the facts in your state where your story takes place, writer.

She stared at me. “The trial date been scheduled?”

“No. And that’s disconcerting.”

“How long has she been awaiting trial?”

“Eighteen months and counting.”

Doctor Riley pursed her lips, taking in the information. She never responded too quickly. I wondered if this was a skill taught by her professors at school or honed over time. Given she’s in her mid-fifties, this is an odd thought.

New graph needed her since it’s doc talking, since the last thought was Rebecca’s. “In the grand scheme of things, eighteen months for a high-profile case is not uncommon. As a homicide detective, you know this. Great way to convey what the protag does! The writer could have put this in Rebecca’s thoughts ie “As a homicide detective, I knew that…” But that is so clumsy. Note how much more adroit this is. So why don’t you tell me what’s eating at you.”

I stood. My legs went all rubbery and for a moment I worried they might give out. They didn’t and I walked over to an aquarium. Note that by saving a physical movement for here and giving it to Rebecca rather than the doc, you train focus on REBECCA! Keep the doc stationary and in the background where she belongs. A variety of marine life called this home. My favorite was the Oscar who seemed to rule the tank. Remember, she’s been away from this office for almost a year. I’d have her look for him, almost as a comfort. (Oscars can live 20 years btw) So if the fish is gone now, that could mean something, even just metaphorically, to Rebecca. Who, btw, lost her father, who at one point ruled the tank/home. As a child my father — my biological one not the animal who molested me — I’d use dashes here to set this important thing apart bought me a fishbowl when I turned six. He helped pick out a Beta. But after my father’s death, I could never bring myself to own another fish tank.

Small fix needed for this: As a child, my father…bought me. Change this to: When I was six, my father — my biological one not the animal who molested me — bought me a fishbowl.

Some might find this passage about the fathers heavy-handed but I like it. It’s a shocking revelation, but because the writer wisely couched it in a benign memory-association of a the fish tank, it worked, imho. It also makes me wonder if mom killed dad! But that’s good — to make me wonder!

So, dear writer, I like what you’re doing here. You’ve got an adept hand at gracefully inserting info and backstory. The dialogue is good and the opening promising. As I said, I would read on. But give some thought to massaging that opening graph. There’s a better one in you and Rebecca will thank you for it.

BTW, I like your title because I trust that it comes to really mean something in the context of your plot. Thanks for submitting, keep writing, and good luck!

To master the art of writing we need to read. Whenever the words won’t flow, I grab my Kindle. Reading someone else’s story kickstarts my creativity, and like magic, I know exactly what I need to do in my WIP.

To master the art of writing we need to read. Whenever the words won’t flow, I grab my Kindle. Reading someone else’s story kickstarts my creativity, and like magic, I know exactly what I need to do in my WIP.

“Read” is the easiest writing tip, yet one of the most powerful. And here’s why.

READING BENEFITS OUR WRITING

READING IMPROVES BRAIN HEALTH

Narratives activate many parts of our brains. In a 2006 study published in the journal NeuroImage, researchers in Spain asked participants to read words with strong odor associations, along with neutral words, while their brains were being scanned by a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machine.

Brain scans are revealing what happens in our heads when we read a detailed description, an evocative metaphor or an emotional exchange between characters. Stories, this research is showing, stimulate the brain and even change how we act in life. — New York Times

Whenever participants read words like “perfume” and “coffee,” their primary olfactory cortex (the part of the brain that processes smell) lit up the fMRI machine. Words like “velvet” activated the sensory cortex, the emotional center of the brain. Researchers concluded that in certain cases, the brain can make no distinction between reading about an experience and encountering it in real life. Pretty cool, right?

4 TIPS TO READ WITH A WRITER’S EYE

1. Look for the author’s persuasion tactics.

How does s/he draw you in?

How does s/he keep you focused and flipping pages?

What’s the author’s style, fast-pace or slow but intriguing?

Does the author have beautiful imagery or sparse, powerful description that rockets an image into your mind?

2. Take note of metaphors and analogies.

How did the metaphor enhance the image in your mind?

How often did the author use an analogy?

Where in the scene did the author use a metaphor/analogy?

Why did the author use a metaphor/analogy? Reread the scene without it. Did it strengthen or weaken the scene?

In a 2012 study, researchers from Emory University discovered how metaphors can access different regions of the brain.

New brain imaging research reveals that a region of the brain important for sensing texture through touch, the parietal operculum, is also activated when someone listens to a sentence with a textural metaphor. The same region is not activated when a similar sentence expressing the meaning of the metaphor is heard.

A metaphor like “he had leathery hands” activated the participants’ sensory cortex, while “he had strong hands” did nothing at all.

“We see that metaphors are engaging the areas of the cerebral cortex involved in sensory responses even though the metaphors are quite familiar,” says senior author Krish Sathian, MD, PhD, professor of neurology, rehabilitation medicine, and psychology at Emory University. “This result illustrates how we draw upon sensory experiences to achieve understanding of metaphorical language.”

3. Read with purpose.

As you read, study the different ways some writers tackle subjects, how they craft their sentences and employ story structure, and how they handle dialogue.

4. Recognize the author’s strengths (and weaknesses, but focus on strengths).

Other writers are unintentional mentors. When we read their work, they’re showing us a different way to tell a story—their way.

Ask, why am I drawn to this author? What’s the magic sauce that compels me to buy everything they write?

Is it how they string sentences together?

Story rhythm?

Snappy dialogue?

How they world-build?

Or all of the above?

I don’t know about you but I’m dying to jump back into the book I’m devouring. 🙂 What’s your favorite tip?

Wishing you a safe and happy Memorial Day! In between cookouts and family get-togethers, squeeze in time to read!

Looking for a new series to love?

FOR TODAY ONLY, all four Grafton County thrillers are on sale!

MARRED 99c

CLEAVED 99c

SCATHED $1.99

RACKED $1.99

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Several years ago I tweeted the words that are the title of this post. The phrase went viral (is there such a thing as going bacterial? I’m done with viruses!) It got passed around and was picked up by the great writing tips author Jon Winokur (@AdviceToWriters). The phrase aptly sums up my approach to writing a novel.

I thought today I’d unpack it a little, and ask for your responses.

Write Like You’re in Love

Coming up with a great idea, one that gets your nerve endings buzzing, is like love at first sight. You’re giddy. You can’t wait to spend precious months with this new romance.

Coming up with a great idea, one that gets your nerve endings buzzing, is like love at first sight. You’re giddy. You can’t wait to spend precious months with this new romance.

When you start writing it’s all champagne and moonlight walks on the beach.

But then, out of the blue, you find yourself in an argument. The book is resisting you. Or vice versa.

Usually this happens to me around the 30k mark. I start to think maybe this isn’t going to work out after all.

You say to the book, “You’re not giving me what I need.”

And the book says, “This is how you treat me? After all I’ve done? I’ve given you the best pages of my life!”

Fortunately, I’ve found this little dustup to be only temporary. Let me suggest two ways to kiss and make up with your novel.

First, go more deeply into the characters. Pick any one of them (and not necessarily your Lead) and write some backstory. Create more of their history and use that to come up with a secret or a ghost.

A secret is simply that which the character doesn’t want anyone to know about, for some personal reason related to backstory.

A ghost is an event from the past that haunts the character in the present, and causes the character to act in certain ways. It’s best to let those actions happen without an immediate reveal. It creates mystery for the reader, always a good thing.

Five or ten minutes with these brainstorms will get your story juices flowing again. You’ll want to keep writing just to see what happens to these people!

Second, jump ahead and write a scene you feel excited about. Write it for all it’s worth. Then drop back and pick up the story and figure out a way to get to that scene.

These tips will help keep the love fires burning, like bringing the wife flowers even when it isn’t Valentine’s Day.

(Also see my post “When Writers Hit the Wall.”)

Edit Like You’re in Charge

Once you have a complete draft, you move into the hard-scrapple world of revision. And here you need a system.

Once you have a complete draft, you move into the hard-scrapple world of revision. And here you need a system.

The late Jeremiah Healy was a popular author-speaker on the conference circuit. In one of my writing books I found a clipped page from a newsletter I used to get called Creativity Connection. I’d saved it because it was a summary of one of Healy’s talks. In it he described his system of approach after writing a first draft:

That’s a good system, and very close to the one I use myself.

And systems can often be improved by adding a formula. Here’s one I’ll leave you with. It came in an early rejection letter the young (1966) Stephen King received from a science fiction magazine. It was a form rejection, but the nice editor had scribbled the following on it:

“Not bad, but puffy. You need to revise for length. Formula: 2nd Draft = 1st Draft – 10%. Good luck.”

Now it’s your turn. How do you keep the love as you make your way through the first draft? Do you have a system for revision?

Photo by Kasper Rasmussen on unsplash.com

I have received some correspondence recently to the effect that TKZ has some regular visitors who are not necessarily interested in becoming authors themselves. They stop by because they are interested in how authors engage in the process by which writing is done. They have no inclination towards writing, let alone publishing a story. Think of folks who like to eat but who have no inclination toward cooking. This is aimed at those who enjoy literary feasts but have no inclination toward stirring the pot, though the Emerils in the audience may find it interesting as well.

Our own Jim Bell contributed a deep but highly accessible piece the Sunday last titled “Advice for the Demoralized Writer.” It contains terrific advice which is applicable to all regardless of occupation but the crux of it is to do your very, very best while sublimating your expectations of awards or recognition. If your efforts garner such you will be pleasantly surprised. If not, you won’t be disappointed. I am going to take that advice a step further while aiming it in a different direction.

My suggestion is to write every day. That is not new or original advice. I am offering it particularly, however, to those of you who have no intention of or inclination toward starting or completing a story or having it revealed in the harsh light of day. Writing something every day because you want to, instead of when you have to, is good for you. I truly believe that writing regardless of length or motive makes one smarter — whatever that is — and yes, happier. Writing even one sentence of a few words per day enables you, the unintentional writer, to say, “I wrote this.” It may not give you an adrenaline rush but I submit to you that it will produce, at the least, a drop of it in your cup. It’s the difference between doing an action because you are required to (for reasons from within or without) and doing it because you want to. It can crack the ice that freezes your thinking, whether you write on a post-it, a computer, or your hand. It is an activity that you can do without prompting, or the desire of future reward, other than that occasioned by performing the act itself. I have mentioned this before, but the television series Miami Vice was born as the result of two words handwritten on a piece of paper. The words were “MTV cops.” Your results may differ. That’s the point. There are those who may keep a diary or journal for a similar reason. What I propose is not as involved.

This post is but one example of “wanting to” as opposed to “being compelled to.” I started this post with one sentence, though it is not the introductory sentence that you see above. I wrote a few words to get rolling and then took off, as John Coltrane said, in both directions at once. It was because I wanted to. “The Kill Zone” name notwithstanding, no one here writes with a gun to their head. We are all here because we want to be, whether to write or to read what is written.

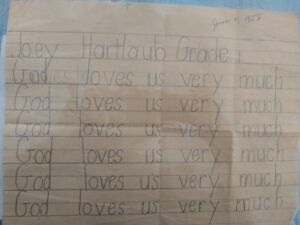

Now we present below an example of some writing that a six-year-old miscreant was compelled to do as a classroom punishment in the closing days of first grade. History has not recorded what the lad did over sixty years ago to earn this assignment. If rehabilitation was the purpose please rest assured that the effort failed miserably. It is a wonder that he ever took pen(cil) to paper again voluntarily, but he did occasionally and still does.

Photo by Al Thumbs Photography. All rights reserved.

Try what I suggest and see what happens. At worst you will have wasted a few seconds. At best, it could be the start of something big. As with most things, the end result may be somewhere in the middle. Don’t worry about that. This is a worry-free activity for enjoyment as opposed to production. Just put a few words down for the fun of it. You might be surprised.

Actually, let’s try it right now. Seven words or less. Go! Here’s mine:

“He wondered where the painter was.”

Have a relaxing Memorial Day. While you do so, please remember the reason for the season. Thank you.

Photo by Justin Casey on unsplash.com

Photo credit: Kal Visuals-Unsplash

By Debbie Burke

So, you’re back on the street after doing time in the federal pen in Fort Dix, New Jersey. You want to earn a little extra income, presumably to pay your defense attorney, and to supply your buddies who are still inside. Nothing big, just cigarettes, cell phones, heroin, and fentanyl.

Why not use a drone to deliver packages—just like Amazon?

Jason Ateaga-Loayza, AKA “Juice”, must have thought that was a good business plan even though he was on supervised release from Fort Dix, a low-security federal correctional facility.

Between October 2018 and June 2019, Juice and several co-conspirators smuggled contraband by drone into the prison. Juice communicated by cell phone texts with an accomplice who was still incarcerated. The accomplice took orders from inmates and collected payments. Juice gathered the requested items and stored them in his home. Then he and other accomplices hid in the woods surrounding Fort Dix and operated a drone from there, dropping packages inside the prison at night. They taped over the lights on the drone to prevent detection.

Evidently the operation succeeded for a while…until FBI agents searched Juice’s home. Officers turned up a closetful of empty cell phone boxes and tobacco containers matching items that had previously been dropped inside the prison. They also found enough heroin and fentanyl to charge him with possession with intent to distribute.

His high-flying entrepreneurial venture has been grounded.

~~~

Bad guys use a drone to surveil the good guys in Debbie Burke’s thriller Eyes in the Sky

Buy at Amazon or major online retailers.

Tips for Dealing With Character Names

Terry Odell

Last week, John Gilstrap addressed coming up with character names, and there were a lot of helpful suggestions in the comments.

Last week, John Gilstrap addressed coming up with character names, and there were a lot of helpful suggestions in the comments.

I tend to hit the Google Machine. “Male (or female) Names Starting with …” is a frequent search. Another thing to add to that search is the year/decade that character was born. Name trends change with time.

I had a shocking realization when seeking a name for a character in a recent book.

Names have to “match” the characters to some extent. For me, it’s a loose match. Our country is so much of a melting pot that names often don’t match one’s ethnicity, and it’s often a stereotype to try to give them “appropriate” names. I recall my daughter, when she was in middle school, asking if her friend Kiesha could come visit. What’s your first visual? Probably not the blue-eyed blonde who showed up. But if I want an ethnic name, I just add that to my Google search.

This week, I thought I’d expand on John’s topic, because coming up with names is only part of the problem. You’ve cleared the choosing names for your characters hurdle. But there are pitfalls to avoid so you don’t confuse your readers.

A tip I picked up at a workshop was the reminder that the characters should sound like their parents named them, not you.

Major warning: Names shouldn’t be too similar to other characters in the book.

This mean no Jane and Jake, or Mick and Mack, or Michael and Michelle—and that includes nicknames. If everyone calls Michael Mike, and there’s another character named Norman, but Norman’s last name is MacDonald and everyone calls him Mac, then you’re setting things up for reader confusion. I recently read a book where the author had fixated on the letter B for character names, and these were major players, not bit parts. I don’t think I ever got them straight.

Many readers see the first few letters of a character’s name and connect it to whatever image they’ve created for that character. Your character might be named Anastasia, but the reader might be thinking “The blonde woman with the A name.”

So, how do you keep track so you don’t confuse or frustrate your readers? Here’s my system.

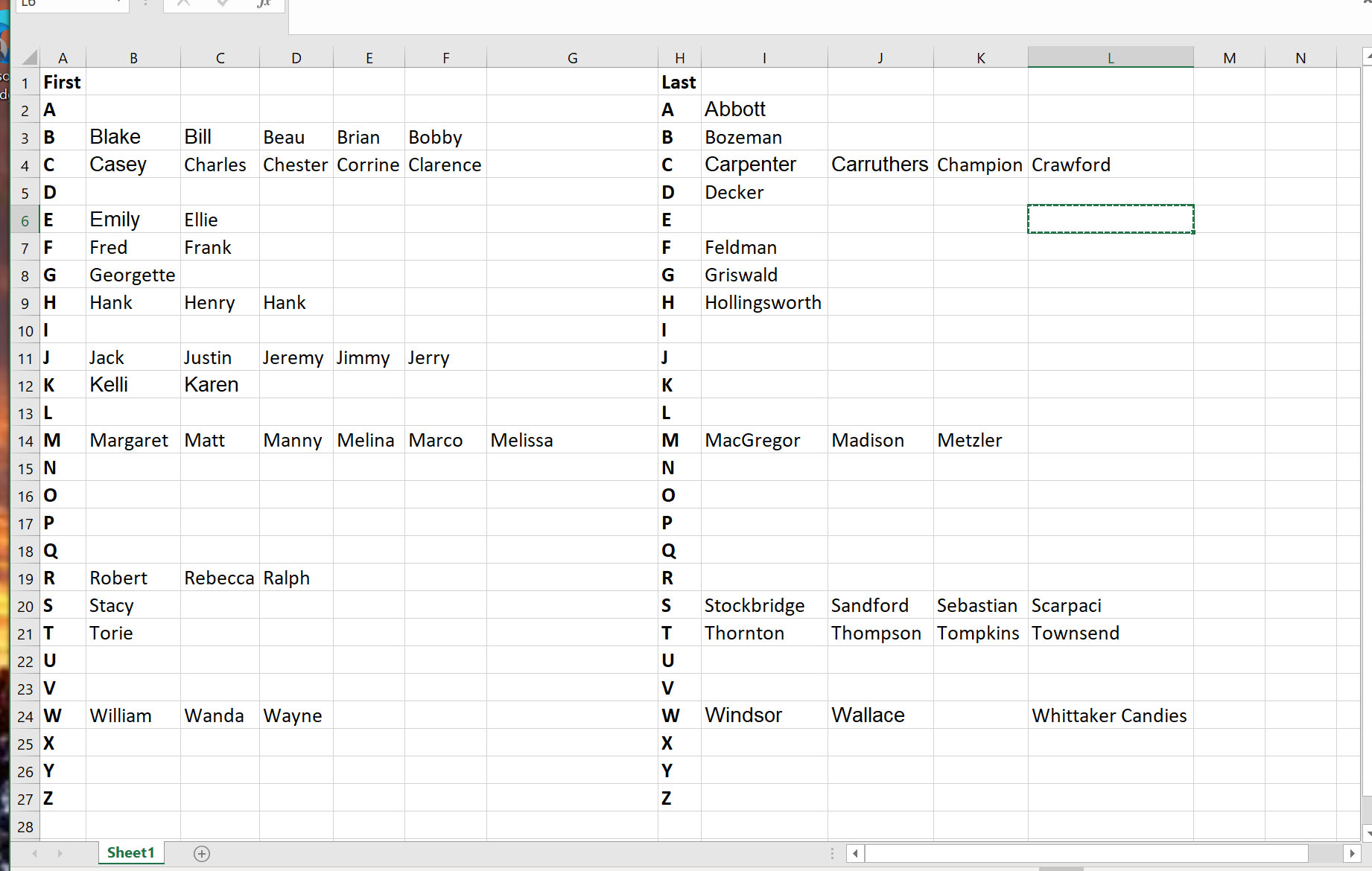

The late Jeremiah Healy prefaced one of his workshops with a very vocal complaint about character names in books. He said, “How hard is it to take a sheet of paper, write the alphabet in two columns, and then put first names in one, last names in the other?”

Now that we’re using computers, instead of a sheet of paper, I use a simple Excel spreadsheet. When I name a character, I fill in a blank field in the appropriate line. This lets me see at a glance when I start to fixate on a letter. I hadn’t been to Healy’s workshop when I wrote What’s in a Name? but when rights reverted to me, I used the spreadsheet and was shocked at what I’d discovered. THREE characters named Hank? Okay, only two, but the third was Henry “but you can call me Hank.” I still haven’t forgiven my then editor for that one.

This is what I found when I went through the book:

(You can click to enlarge the images)

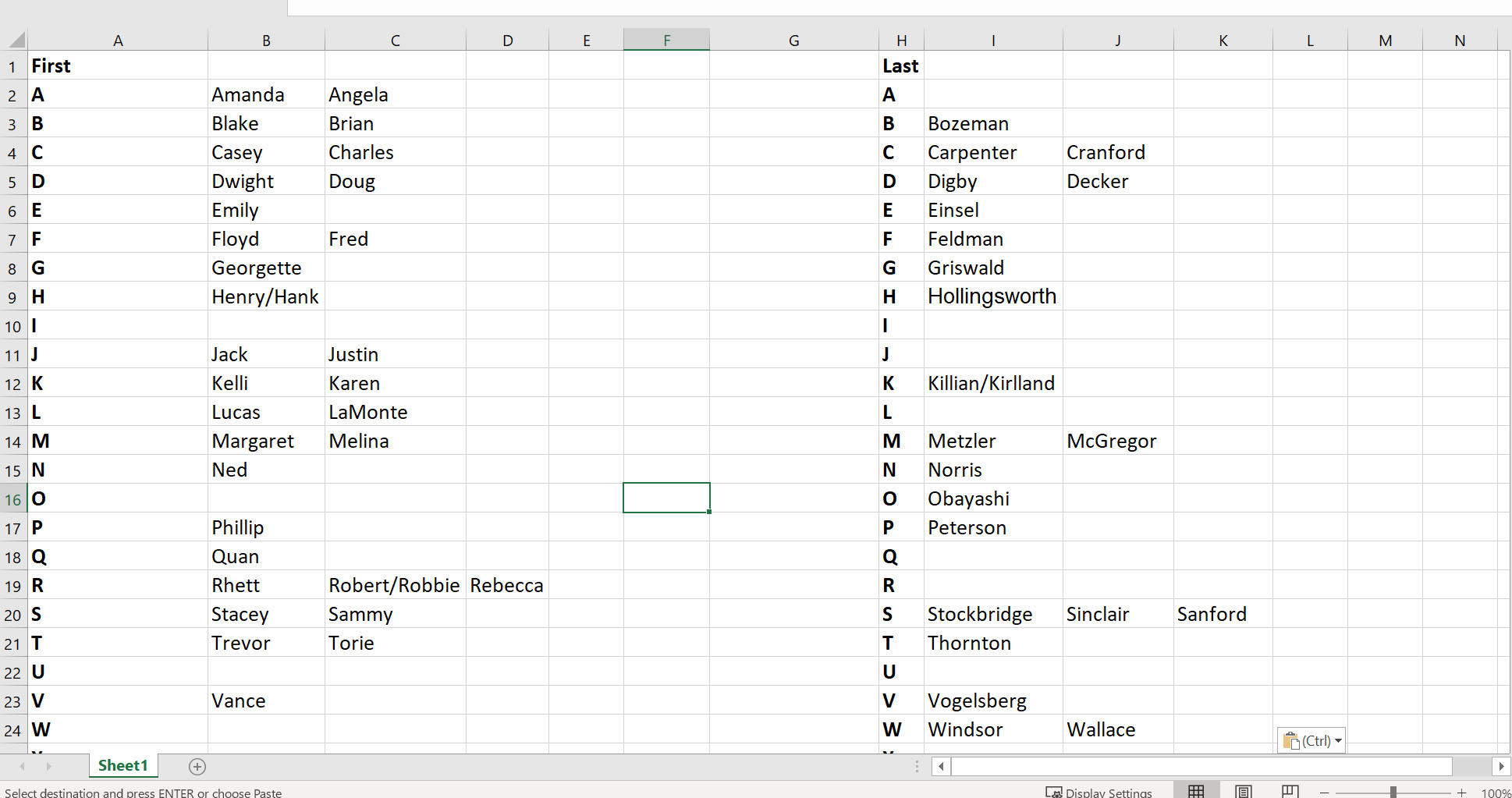

In addition to making minor revisions to the text, you can be sure I updated the character names. Here’s the “after” spreadsheet.

In addition to making minor revisions to the text, you can be sure I updated the character names. Here’s the “after” spreadsheet.

Other considerations. Foreign names might be realistic, but what if a reader is unfamiliar with the name, or its pronunciation? One of my critique partners wrote a book with a family of Irish descent, and she’s calling one of the characters Siobhan. (If I were naming a character that, the first thing I’d do would be to set up an auto correct, because I’d probably spell it wrong more often than not.) But typing it right is the author’s problem, not the reader’s. Do you know how to pronounce Siobhan? (shi-VAWN) If the author tells you, when you see the word do you “hear it” or is it strictly a visual?

Other considerations. Foreign names might be realistic, but what if a reader is unfamiliar with the name, or its pronunciation? One of my critique partners wrote a book with a family of Irish descent, and she’s calling one of the characters Siobhan. (If I were naming a character that, the first thing I’d do would be to set up an auto correct, because I’d probably spell it wrong more often than not.) But typing it right is the author’s problem, not the reader’s. Do you know how to pronounce Siobhan? (shi-VAWN) If the author tells you, when you see the word do you “hear it” or is it strictly a visual?

(With apologies to Brother Gilstrap, I never see/hear his character Venice as Ven-EE-chay, no matter that he’s made the pronunciation clear. To me, she’s “Not Venice” in my head.)

And then, there’s a whole new set of problems. Audiobooks. When I started to put my books into audio, I had to focus on what things sound like as well as look like. In my third Triple-D Ranch book, the heroine’s ex-husband’s name is Seth. Her sister’s name is Bethany. They don’t look very similar on the page, but when spoken, I’m concerned that they’ll sound too much alike, especially if they’re in the same sentence. Or even paragraph. I don’t want my narrator stumbling (or calling them both Sethany).

All right, TKZers. Share your tips for keeping track of character names.

Now available for Preorder. Trusting Uncertainty, Book 10 in the Blackthorne, Inc. series.

Now available for Preorder. Trusting Uncertainty, Book 10 in the Blackthorne, Inc. series.

You can’t go back and fix the past. Moving on means moving forward.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.” Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.