Many contemporary psychologists believe there are five primary dimensions to our personalities. In their business, psychological experts refer to the categories as the “Big Five” personality traits. They are openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (OCEAN). You could also list them as conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, openness, and extraversion (CANOE).

The Big Five has surpassed the Myers-Briggs Personality Test and the Enneagram as currently used, open-source psychological assessment tools. I’ve taken both the Myers-Briggs and the Enneagram and found them quite descriptive as I see myself to be. But then, I’m a Libra and Libras tend to agree with pretty much everything.

What got me going on the Big Five, and why it might be useful as a characterization tool for fiction writers, was Jordan Peterson. For those who don’t know of Dr. Jordan B. Peterson, the New York Times described him as “The most influential public intellectual in the western world right now”. Dr. Peterson is a clinical psychologist and the author of a wildly successful book 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos.

Our daughter bought tickets for my wife and me to see Jordan Peterson live a few weeks ago. I certainly knew who Jordan Peterson is. Although I’ve never read his book, I’ve watched/heard several of his podcasts, and the guy always makes sense to me. I know he’s vilified by the woke progressives, and that pissing them off is precisely what he attempts to accomplish.

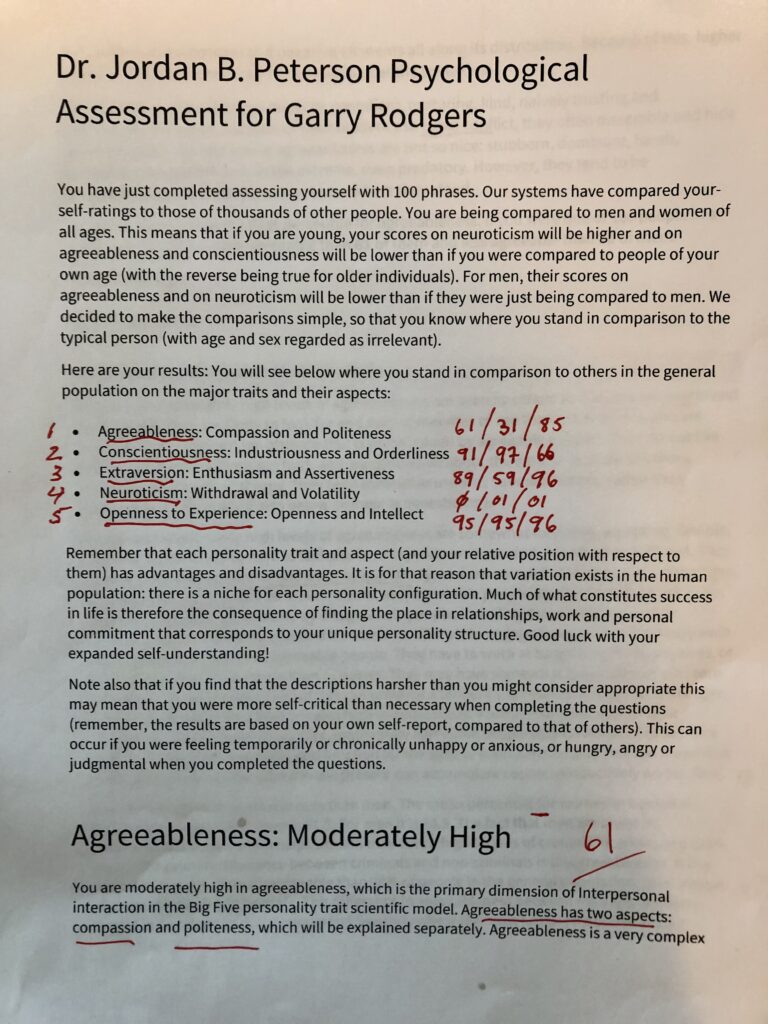

Dr. Peterson didn’t invent the Big Five Personality Traits, but he wholeheartedly endorses them. So much so that he offers a short assessment called Understand Myself which produces an individual psychological assessment report on how you fit within the Big Five. It takes about twenty minutes and costs ten bucks. I found it an interesting exercise. So much so that I signed up for his five-hour, seven-module online course for eighty bucks.

It was money well spent. Not to find out that I don’t have a neurotic bone in my body and that I’m quite low on compassion, but to learn that this Big Five psychological breakdown/assessment has great potential as a tool for character building. So much so that I’m already applying it to developing characters in my WIP titled City Of Danger.

What are the OCEAN / CANOE traits and how do they involve secondary supportive psychological categories? Let’s have a quick look.

1. Agreeableness is kindness. It includes attributes like trust, altruism, affection, and other prosocial behaviors. Agreeableness has two subcategories—compassion and politeness.

2. Conscientiousness is thoughtfulness. It’s defined by factors like impulse control and goal-directed behaviors. Conscientiousness has two subcategories—industriousness and orderliness.

3. Extraversion (Extroversion) is sociability. Traits are characterized by measuring excitability, talkativeness, assertiveness, and emotional expressiveness. Extraversion has two subcategories—enthusiasm and assertiveness.

4. Neuroticism involves sadness and emotional instability. It includes things like mood swings, anxiety, and irritability. Neuroticism has two subcategories—withdrawal and volatility.

5. Openness is creativity and intrigue. Being open is being imaginative and having insight. Openness has two subcategories—experience and intellect.

Okay. That’s the CliffsNotes of the Big Five Personality Traits. Now, how did I score from 0 to 100 (low to high) on Jordan Peterson’s Understand Myself test? Here goes:

Agreeableness—61 Compassion—31 Politeness—85

Conscientiousness—91 Industriousness—97 Orderliness—66

Extraversion—89 Enthusiasm—59 Assertiveness—96

Neuroticism—0 Withdrawal—1 Volatility—1

Openness—95 Experience—95 Intellect—96

Moving on to applying the Big Five to characterization, I took my arch-villain, Klaus Rothel in my City Of Danger project, and ran him through Dr. Peterson’s Understand Myself questionnaire. To my surprise, or maybe not to my surprise, Klaus Rothel has almost the same personality as me. Except for compassion. Klaus scores even worse than me there.

I like the Big Five Personally Trait test for characterization. So much so (yes, I know I’ve overused “so much so” but I like “so much so” and it’s my TKZ blog post turn today so the so-much-sos stay) that I plan to run all my characters in the City Of Danger series through the Big Five test. It really makes you think about who they are, what they think, and how they’ll act.

Kill Zoners—Has anyone out there heard of, or used, the Big Five psychological evaluation for character development or even for getting to know yourself better? Also, how do you go about building fictional characters?

I’m on an even-newer venture right now, and that’s developing a net-streaming style series. It’s a different—but not too different—delve into hardboiled detective fiction, and the series is titled City Of Danger. To write this credibly, and with honor to heritage, I’ve plunged into a rabbit hole of research that’s becoming more like a badger den or a viper pit.

I’m on an even-newer venture right now, and that’s developing a net-streaming style series. It’s a different—but not too different—delve into hardboiled detective fiction, and the series is titled City Of Danger. To write this credibly, and with honor to heritage, I’ve plunged into a rabbit hole of research that’s becoming more like a badger den or a viper pit. Picture a Roman arch bridge. Every stone is held in place by its neighbor just like story archs with properly set scenes. Take away one scene that doesn’t support the story arch and the structure fails.

Picture a Roman arch bridge. Every stone is held in place by its neighbor just like story archs with properly set scenes. Take away one scene that doesn’t support the story arch and the structure fails.

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective and coroner with over thirty years experience in human death investigation. Now, Garry has reinvented himself as a crime writer with his latest venture into a hardboiled detective fiction series called City Of Danger. Here’s the logline:

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective and coroner with over thirty years experience in human death investigation. Now, Garry has reinvented himself as a crime writer with his latest venture into a hardboiled detective fiction series called City Of Danger. Here’s the logline: