Crime doesn’t pay, so they say. Well, whoever “they” are, they aren’t in touch with today’s entertainment market because crime—true and fiction—in books, television, film, or net-streaming, is a highly popular commodity. One solid crime writing sub-genre, detective fiction, is hot as a Mexican’s lunch.

Detective fiction has been hot for a long, long time. Crime writing historians give Edgar Allan Poe credit for siring the first modern detective story. Back in 1841, Poe penned Murders In The Rue Morgue (set in Paris), and it was a smash hit in Graham’s Magazine. Poe’s detective, C. Auguste Dupin, used an investigation style called “ratiocination” which means a process of exact thinking.

Poe’s style brought on the cozy mysteries, aka The Golden Era of Crime Fiction of the 1920s. Detectives like Sherlock Holmes and Miss Marple solved locked-room crimes. They intrigued readers but spared them gruesome details like extreme violence, hardcore sex, and graphic killings.

The golden crime-fiction genre evolved into the hardboiled detective fiction movement, circa 1930s-1950s. Crime writers like Dashiell Hammett gave us the Continental Op and Sam Spade. Raymond Chandler brought Philip Marlowe to life. Carroll John Daly convincingly conceived Race Williams. And Mickey Spillane, bless his multi-million-selling soul, left Mike Hammer as his legacy.

The ’60s to 2000s gave more great detective fiction stories. Anyone heard of Elmore Leonard? How about Sarah Paretsky and Sue Grafton? Or, in current times, Michael Connelly, Megan Abbott, and a wildcard in the hardboiled and noir department, Christa Faust?

These storytellers broke ground that’s still being tilled by great fictional detectives. Television gave us Perry Mason, Ironside, Columbo, Jack Friday, Kojack, and Magnum. Murder She Wrote? How cool was mystery writer and amateur detective Jessica Fletcher? And let’s not even get into big screen and the now runaway net-stream stuff.

So why the unending popularity of detective fiction? I asked myself this question to understand and appreciate the detective fiction part of the crime story genre. I worked as a real detective for decades, and I know what it’s like to stare down a barrel and scrape up a cold one. But once I reinvented myself as a crime writer, I had to learn a new trade.

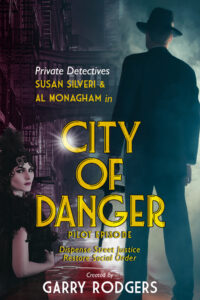

I’m on an even-newer venture right now, and that’s developing a net-streaming style series. It’s a different—but not too different—delve into hardboiled detective fiction, and the series is titled City Of Danger. To write this credibly, and with honor to heritage, I’ve plunged into a rabbit hole of research that’s becoming more like a badger den or a viper pit.

I’m on an even-newer venture right now, and that’s developing a net-streaming style series. It’s a different—but not too different—delve into hardboiled detective fiction, and the series is titled City Of Danger. To write this credibly, and with honor to heritage, I’ve plunged into a rabbit hole of research that’s becoming more like a badger den or a viper pit.

What I’m doing, as we “speak”, is learning this sub-genre of crime writing—hardboiled detective fiction—and I’ve learned two things. One, I found out I knew SFA almost nothing about this fascinating fictional world that’s entertained many millions of detective fiction fans for well over a hundred years. Two, detective fiction has far from gone away.

My take? Detective fiction—hardboiled, softboiled, over-easy, scrambled, or baked in a cake—is on the rise and will continue being a huge crime-paying moneymaker in coming years. There are reasons for that, why detective fiction remains so popular, and I think I’ve found some.

I stumbled on an interesting article at a site called Beemgee.com. Its title Why is Crime Fiction So Popular? caught my attention, so I copied and pasted it onto a Word.doc and dissected it. Here’s the nuts, bolts, and screws of what it says.

Crime fascinates people, and detectives (for the most part) work on solving crimes. But the crime genre popularity has little to do with the crime, per se. It has far more to do with the very essence of storytelling—people are hardwired to listen to stories, especially crime stories.

Detective fiction is premiere crime storytelling and clearly exhibits one of the fundamental rules of storytelling: cause and effect. In detective fiction, every scene must be justified—each plot event must have a raison d’etre within the story because the reader perceives every scene as the potential cause of a forthcoming effect.

Picture a Roman arch bridge. Every stone is held in place by its neighbor just like story archs with properly set scenes. Take away one scene that doesn’t support the story arch and the structure fails.

Picture a Roman arch bridge. Every stone is held in place by its neighbor just like story archs with properly set scenes. Take away one scene that doesn’t support the story arch and the structure fails.

Well-written detective fiction has a bridge-like structure. Each scene in the storytelling trip has some sort of a cause that creates an effect. This subliminal action keeps readers turning pages.

The article drills into detective fiction cause and effect. It rightly says the universe has a law of cause and effect but we, as humans, can’t really see it in action. But we’re programmed to know it exists, so we naturally seek an agency—the active cause of any actions we perceive.

Detective fiction stories, like most storytelling types, provide a safety mechanism. A detective story is built around solving a crime by following clues. A cause. An effect. A cause. An effect. The story goes on until you find out whodunit and a well-told story leaves you with a satisfying end where you’ve picked up a take-away safety tip.

But detective fiction stories aren’t truly about whodunit. Sure, we want the crook caught and due justice served. However, we want to know something more. We want to know motive, and this is where the best detective fiction stories shine. They’re whydunnits.

Whydunnits are irresistible stories. They’re the search for truth, and in searching for truth in detective fiction storytelling—why this crime writing sub-genre remains so popular—I found another online article. Its title Why Is Detective Fiction So Popular? also caught my attention.

Cristelle Comby

This short piece is on a blog by Swiss crime writer, Cristelle Comby. If you haven’t heard of Cristelle, I recommend you check her out. Her post has a quote that sums up why detective fiction is so popular, and it’s far more eloquent than anything I can write. Here’s a snippet:

“Detective novels do not demand emotional or intellectual involvement; they do not arouse one’s political opinions or exhaust one by its philosophical queries which may lead the reader towards self-analysis and exploration. They, at best, require a sense of vicarious participation and this is easy to give. Most readers identify themselves with the hero and share his adventures and sense of discovery.

The concept of a hero in a detective story is different from that of a hero in any other kind of fictional work. A hero in a novel is the protagonist; things happen to him. His character grows or develops and it is his relationship to others which is important. In a detective story, there is no place for a hero of this kind. The person who is important is the detective and it is the way he fits the pieces of the puzzle together which arouses interest. Thus in a detective story it is the narration and the events which are overwhelmingly important, the growth of character is immaterial. What the detective story has to offer is suspense. It satisfies the most primitive element responsible for the development of story-telling, the element of curiosity, the desire to know why and how.

Detective stories offer suspense, a sense of vicarious satisfaction, and they also offer escape from the fears and worries and the stress and strain of everyday life. Many people who would rather stay away from intellectually ‘heavy’ books find it hard to resist these. Detective fiction is so popular because the story moves with speed.”

As a former detective, and now someone who writes this stuff, I think detective fiction is so popular because readers can safely escape into a dark & dangerous world of wild causes and wild effects—full of fast-reading suspense—and they get powerful insight into what makes other people (like good guys and bad girls) tick. Detective fiction is crime that has paid, does pay, and always will pay. It’s just that popular.

Kill Zone readers and writers: If you’re into detective fiction, what do you think makes it popular? And if you’re not into the genre, what makes you dislike it? Don’t be shy about commenting one way or another!

——

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective and coroner with over thirty years experience in human death investigation. Now, Garry has reinvented himself as a crime writer with his latest venture into a hardboiled detective fiction series called City Of Danger. Here’s the logline:

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective and coroner with over thirty years experience in human death investigation. Now, Garry has reinvented himself as a crime writer with his latest venture into a hardboiled detective fiction series called City Of Danger. Here’s the logline:

A modern city in dystopian crisis enlists two private detectives from its utopian past to dispense street justice and restore social order.

Follow Garry Rodgers on Twitter and visit his website at DyingWords.net.

A lot to digest this early, but the reason I like detective fiction is there’s (almost) always a solution. Good triumphs over evil. However, I like stories that go beyond the workday. Bosch has his personal problems and shows growth across the series. Lucas Davenport has a family. So does Virgil Flowers. I read as much for what’s happening ‘behind the crime’ as I do for the solution. Eve Dallas always gets her “man” but she’s gained more character depth across the series.

So, I disagree with these words: Thus in a detective story it is the narration and the events which are overwhelmingly important, the growth of character is immaterial.

It’s too early in the morning for me to digest anything, Terry. I’m still into black coffee. I guess this character growth issue goes to whether the story is written as plot-driven or character-driven. I’ve done a series of based-on-true-crime books where they’re all about storyline of what happened in the crimes and how they were solved – there’s not a whiff of character growth or change in them. But that’s true crime. I’ve got my work cut out for me in this detective fiction series. BTW, I wrote this article as much for me to understand the sub-genre as anything. Thanks for your comment.

Of the detective genre I’ve read, the overwhelming majority have only a minuscule character arc for the detective, if any. Sherlock Holmes gave up cocaine, and that was about it. And so on.

I question whether a police procedural qualifies as a detective novel. The feel is entirely different. The detection is spread over multiple characters.

I agree with you about a PP being different than a detective novel. My series is much more PP than a detective adventure, but I never set out to write a specific genre/sub-genre. I just had real stories to tell so I flew at it. Now, with this dive into old-style hardboiled, I’m going to really think out how this is done. Thanks for your comment, JGA.

Garry, great analysis of why the detective fiction genre is popular. Readers are hungry for answers as to how and why violence and evil happen.

You nailed it with this observation: “readers can safely escape into a dark & dangerous world of wild causes and wild effects—full of fast-reading suspense—and they get powerful insight into what makes other people (like good guys and bad girls) tick.”

Another reason I think crime fiction has enduring popularity: justice triumphs over injustice. That’s reassuring in the real world where justice is too often denied.

Congratulations on your streaming venture. Looking forward to hearing more about it.

Gotta ask–what is SFA?

Thank you, Debbie. This piece was self-serving because I wrote it to try and make sense of the subject’s core. When I said I knew SFA about hardboiled history, tropes, terms, and a whole lot more that makes up a fascinating (to me) chunk of crime writing history, I meant it. SFA? It means Sweet F*** All: 🙂

Figured SFA was something along those lines but couldn’t find it in the urban dictionary. Must be Canuck slang 😉

Another source for such things Debbie:

https://www.internetslang.com/SFA-meaning-definition.asp

Thanks, Lars.

Great post, Garry. I love your writing style, which is very refreshing.

became interested in detective fiction at a very early age when I was just learning to read and discovered Dick Tracy by Chester Gould in the newspaper comic strip section. The characters were each and all unforgettable, from Tracy and Sam Ketchum to the villains such as Wormy and Measles. The attraction was that Tracy was a righter of wrongs, no more, no less. I also religiously read the “Crimestopper’s Textbook” in the Sunday comics section which now that I think of it probably influenced a portion of my vocational career. I read Tracy for decades, but also picked up the Hardy Boys, then Shell Scott (quite a jump, let me tell you), Sherlock Homes, Peter Whimsey, and the list goes on and on, still with that “righter of wrongs” theme.

There you have it. Thanks for jump-starting my day, Garry.

Hey, thanks, Joe. I write like I talk, so if we meet in person one day, which I hope we do after this pandemic is long forgotten, you’ll hear my voice come through. Only I swear more in person than I put on the page.

Dick Tracy! Loved that comic series. Is it still around or in reprint? I gotta tell a quick cop insider. We had a lady detective on the squad (a very good detective, BTW) and you had know her nickname was Dickless Tracy.

According to my dad, when LAPD hired “Meter Maids” they called them Dickless Tracies. I think that’s the only job women could have in the police force back then.

In the steel mills around here, the guy who placed the hooks on the huge bucket of molten steel to set up for pouring was called a “hooker” naturally. The job title had to change when females entered this line of work.

When I worked in the deep south in a chemical plant, a series of chemical reactors were chilled to -155F and when it came time to put them on line by raising the temperature slightly to -130F, the process was called, “Getn ‘er hot and ready.”

When the time came to start the reaction, the order was given as, “Sticking it to ‘er.” meaning the field technician was to open the valve and admit the catalyst stream.

An exciting point in everyone’s morning because at this point an entire building filled with engines from 800 to 2,300 horsepower roared to life in the struggle to keep the temperature from rising to -120F at which an uncontrollable thermal runaway would start. Time to hit the kill button and run.

Obviously when females entered the workforce, more genteel descriptions had to be used.

I love detectives from Miss Marple to Jessica Fletcher to Kinsey Milhone to Michael Bennett and this week catching up with Alex Cross while I’m on vacation.

Years of Catholic school gave me a strong sense of justice. The real world may not always deliver but our fictional detectives do.

Sometimes I dip my toe in the detective pool. While I was working Horror Nights at Universal I spent my time off set in the green room writing The Theme Park Murders. Good times!

From personal observation, I have to agree with you on Catholic justice views, Cynthia. My wife and daughter are French Canadian Catholics (I’m the Irish Protestant in the house 🙂 and they have no time – zero, zip – for injustice. I’m surprised they don’t wear capes. Thanks for reading and commenting!

I was raised in a Catholic household and I still remember getting my face slapped by a black robed nun towering over me. My offense was committing hypothetical murder, hers.

She was trying to teach college level ethics to a class of 4th graders. From her ethical POV, if one followed a prescribed set of rigid rules, you would be free of sin and pass right through the pearly gates. My ethical POV was consequentialism meaning one had to look at the consequences of one’s actions. Further, deciding not to take any action was still a decision and therefore an action for which one had to take ownership of. The classical street car ethical dilemma.

Her hypothetical case was a lifeboat filled to capacity, one more person trying to get in would sink it and everyone would die. What would I do if she were swimming to my lifeboat and trying to get in. My answer of using a boat oar to push her away in order to prevent killing everyone in the boat was not the right answer. “Thou shall not kill.” was absolute in any and all cases. Hence the face slap.

She was lucky my boat oar was just a hypothetical one.

Great post, Garry.

Reasons: I agree with Debbie.

1. “safely” escape into a dark and dangerous world…

2. Justice triumphs

3. I would add: the intellectual process of finding the pieces of the puzzle and putting them together until a picture emerges from the chaos

Congrats on the new net-streaming series. I hope that it will be a huge success. Let us know when we should start looking for it.

Hi Steve, Happy Thursday and thanks for showing up as you always do. You nailed it with this: “the intellectual process of finding the pieces of the puzzle and putting them together until a picture emerges from the chaos.” I really think readers want to follow along – hopefully to solve the crime before the detective does. I wish I had that help back in the day.

The film end is not 100% yet – getting green lit is a long way out, but I’m moving ahead with the ebook end no matter what happens. I’ve had this concept in mind for a few years and it fell into place several months ago when I was talking with a film producer about a historical true crime case I worked on that they want to put on the screen. The talk then went to him asking, “So what else you got going?” I pitched the City Of Danger concept. There was long pause before, “…Really…. this is exactly what my colleague at ******* is looking for.” That led to several Zoom sessions and an agreement to keep this alive while I flesh out the series. I stopped my true crime series, did a 180, and now I’m over my head in this hardboiled detective fiction stuff. And lovin’ it!

I think you nailed it. I totally forgot about solving the puzzle! You and the detective get the same clues. Yes I have gone back to see where I missed Col. Mustard picking up the pipe as it were.

As a Sherlockian, I find the skill set that detectives have fascinating. The contrast in good and evil and the unusual settings fun.

They tend to live by a code, such as Spenser.

This is a fun genre.

Hi Warren! In my experience, there’s a lot in common between fictional and real detectives. I started in the dick biz at an early service level. One of the old detectives saw something in this young buck and mentored me. One of the first principles he taught me was “ratiocination” or critical/logical/exact thinking. I never forgot it. I also never forgot his other main principles of Occam’s razor – when presented with two conflicting hypotheses, the simpler one is usually the correct on – and the stranger the case, the closer to home the answer is.

Excellent breakdown, Garry. Detective fiction requires — dare I say — some advanced planning to properly plant clues. Otherwise, if it’s pantsed, the writer needs to go back and plant clues afterward. 😉

And there’s nothing wrong with going back and planting clues–or anything else, regardless of genre. Character needs an older brother? Go back and add it. Allergic to shellfish? No problem. Maybe writing a mystery is akin to solving one.

🙂

Sue – you, my dear friend, are going to win this plotter/pantster thing once and for all. I’m almost ready to concede, roll over, and show my bare belly. I got away with writing into the dark in my last series because I knew the stories inside out, but this detective fiction series? Bhewwepff. This has to be carefully outlined or it’s not gonna woik. Look to the west and you’ll see a white flag being raised over Vancouver Island.

Garry, I love the hardboiled beat, and covered some of the ground in a recent post.

And to piggyback on Terry’s early comment, there really are two kinds of series characters: those who grow, battle, transform inside; and those who remain steady and consistent. Frankly, both are popular, so it’s a matter of preference.

I lean more toward the “inside” game. The great Michael Connelly has said the best crime novel is not just about how the detective works the case; it’s about how the case works the detective. That he has managed this in book after book is really quite astounding.

Then there’s a Reacher-like character, and readers come back because they love what saw in the last book. I heard Lee Child say that when he opens a bottle of Dom Perignon he would be severely disappointed if it didn’t taste like Dom Perignon.

Interestingly, the hardest of the hardboiled eggs, Mike Hammer, had an intense inner life, so it wasn’t just about the thugs, dames, and gats. (My series hero, Mike Romeo, has that first name for a reason).

Welcome to the mean streets, Garry. In the famous words of Raymond Chandler:

Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. He is the hero; he is everything. He must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man. He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honor—by instinct, by inevitability, without thought of it, and certainly without saying it. He must be the best man in his world and a good enough man for any world.

He will take no man’s money dishonestly and no man’s insolence without a due and dispassionate revenge. He is a lonely man and his pride is that you will treat him as a proud man or be very sorry you ever saw him.

The story is this man’s adventure in search of a hidden truth, and it would be no adventure if it did not happen to a man fit for adventure. If there were enough like him, the world would be a very safe place to live in, without becoming too dull to be worth living in.

Thanks so much for the mean streets welcome, Jim. I have some tough acts to follow, including yours. It was in my mind what you’d think of this. I’m well aware of your fondness for the hardboiled greats. I was fortunate to recently pick up a like-new hardcover of Mickey Spillane’s Five Complete Mike Hammer Novels – I, The Jury – Vengeance Is Mine – The Big Kill – My Gun Is Quick – Kiss Me, Deadly. I started into I, The Jury last night. Man, no holds-barred with this writing.

Also, thanks for the Chandler quote. I’ve put it on a Word.doc to print off and memorize.

Bravo, Garry! This is a terrific look at what makes detective fiction tick. Your research skills are first rate, too. You would have made a fine reference librarian 🙂

I enjoy detective fiction because I like seeing good triumph over evil and justice over injustice. Watching the sleuth solve the mystery, putting the clues together and discovering the motive, is very satisfying, in the context of that triumph of good and justice.

My favorite detective fiction has character growth, often over the course of multiple books. Lawrence Block’s Matt Scudder, a former NYPD detective turned private eye, drank to excess in order to numb himself to the pain of the event that had forced him to quit being a cop. He eventually had to reckon with that drinking and the void in his life. Kate Atkinson’s brilliant Case Historiesthe first Jackson Brodie novel, is both a compelling odyssey in solving a set of mysteries by former British cop Brodie, now a private eye, but also features Jackson’s own story.

It’s the character moments that elevate detective fiction into compelling emotional reads and emotional viewing. I’m also a fan of humor, both as a reader and a writer. The contrast between the pathos of the murder and the bathos of the detective’s life adds to the emotional ride the reader is on.

Thanks for a very fun, deep dive into what makes detective fiction so popular.

Bow taken, Dale, however I have to say I’d make a terrible librarian. I’m much too vulgar and violent. Character growth vs plot growth… oh, man, I really don’t know how my City Of Danger series is going to play out. I’m coming to the sad, sad realization (Sue Coletta) that I’m in for a long, long, long outline. It’s going to be an emotional ride.

Fascinating, says Mr. Spock. …people are hardwired to listen to stories. Too true.

I do like detective/crime/thriller stories for this reason:

Simply put, I just like to see the bad folks get what’s coming to them. That’s why I like cowboy stories (upon which all detective stories and others are based, I read somewhere).

What’s hard is when I can’t quite figure out who the bad guy is, because the writer gave him/her a few nice qualities, like in Godfather. Michael and his dad were definitely bad guys, but you can’t hate them completely because, dang it! they love their families. Tongue in cheek, of course. No person is completely good or completely evil and the antag needs at least one pet-the-dog scene.

Or a Save-The-Cat scene, Deb. I recently read STC as part of this understanding screenwriting venture.

I completely believe people are hardwired for story listening. I don’t know if you, or other TKZ folks, have read Lisa Cron’s Wired For Story https://www.amazon.com/Wired-Story-Writers-Science-Sentence/dp/1607742454/. IMO, this is a must-know science for all storytellers.

Speaking of storytelling, now that I have everyone’s attention, in a past life I was involved in the First Nations (American Indian) sweat lodge culture. My mentor, a highly experienced medicine man, was a mesmerizing storyteller. His ability to grip attention and paint mind pictures was outstanding. I miss those days…

I second your nomination of Wired for Story by Lisa Cron. Excellent book!

Have you seen Lisa Cron’s TED Talk, Debbie? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=74uv0mJS0uM BTW, I read a book on TED Talk structure that says most, if not all, top Ted’s start with the presenter telling a story.

I was first introduced into detective fiction when I picked up a book by John Creasy. I fell instantly for the genre and read them for years. With Creasy’s books that is possible. The man wrote over six hundred books using 28 different pseudonyms.

I of course then turned to Agatha Christy, Patterson, and others – several of which are contributors here. 😀

I agree, the genre will always be popular for the reasons you stated.

Can you imagine writing 600 books? I have a hard time some days writing 600 words. Thanks for the name John Creasy, Cecilia. I have a growing list of detective fiction writers to explore and you’ve given me another to add.

Detective fiction has also been one of the plot linchpins of urban fantasy which has a mystery through plot in a world with magic. That’s one of the reasons the “Dresden Files” with PI Wizard Harry Dresden is considered the Gold Standard of urban fantasy.

On another note, Garry, an episode of KINDRED SPIRITS a few weeks ago was about the Rebecca Cornell murder which was supposedly the first and only murder trial where the murder victim’s ghost started the investigation and “testified” about her murder. I thought to myself that makes no sense because of the Zona Shue case, did some searching, and found your excellent Huff article on the Shue case. Very well done.

The Cornell ghost testimony proved to be nonsense. In the trial transcript, the ghost didn’t say she was murdered, if she appeared at all, and the so-called witness of the ghost railroaded the poor son in a case where none of the physical evidence, even for the time, indicated murder. The story must have been conflated in public memory with the Shue case.

Thanks for the nice feedback on the Zona/Trout Shue case, Marilynn. I found it interesting and credible enough to report on. I’m very skeptical about the “paranormal” and believe everything, regardless how bizarre, has a scientific explanation. Having said that, I was involved in one file where something completely inexplicable happened to some extremely experienced detectives. I might just write a Kill Zone post on it and leave it to you folks to determined if we were drunk, stoned, or downright crazy 🙂 And thanks for always sharing your wealth of writing knowledge!

I’d very much like to read that.

My family has been “haunted” by my dad for over 40 years as he’s watched over us, warned us, and acted as guardian angel to his only grand daughter. It freaks out others when my family full of Ph.Ds. in the sciences and psychology comment positively when the topic of ghosts comes up.

You should write that post.

My great-grandfather’s house was haunted, but it was all family.

I’m new to fiction writing and my comments will undoubtedly show it. I love reading “who done its” of almost any flavor. The puzzle solving aspect is what intrigues me most.

Been retired for 17 years and have been entertaining myself with various things. My interest turned to writing fiction novels about 2 years ago. My last several years of employment were spent in research and development, a place where even with corporate assets backing you, only one project in 10 or 12 paid off. Got a few patents to my credit.

I’m trying the same R&D approach with my first attempt at writing a fiction novel. I’m okay with an unorthodox approach with perhaps only an 8 or 10% chance of success. I’ve decided to start from what seems a new perspective to me. The readers will know from page 1, “who done it.” The protagonist commits a robbery, oh yes, and a triple murder. The question raised is, “will he get away with it?” in the cat and mouse game that follows.

The clues will be judged by readers on the basis of how effective they think pursuit by the antagonists will be thrown off and for how long. Sub-plots will act as foils, with friends demanding immediate attention to their relatively trivial needs while the protagonist has to balance his own death stakes issues with maintaining the friendships.

I will employ both plot and character driven aspects, trying to gather more wind into my sails. I realize there is a risk of alienating both types of readers, ending up dead in the water. But I see little fun in letting the protagonist take all the risk; I’ll join him.

This sounds like an interesting premise, Lars. I think all writers run the risk of alienating readers all the time, but that goes with the job. The trick is to entertain more readers than you alienate 🙂

Thanks for the encouragement.