“If you write properly, you shouldn’t have to punctuate.” — Cormac McCarthy.

“If you write properly, you shouldn’t have to punctuate.” — Cormac McCarthy.

By PJ Parrish

I guess when you win the Pulitzer Prize for literature, you can do whatever you want. I read McCarthy’s The Road years ago. There are no quote marks to set off the dialogue. There are no commas or question marks. There are periods, but even they are sparse. McCarthy’s pages look as bleak and barren as the story’s apocalyptic landscape.

When I first started the book, the lack of punctuation annoyed me. It wasn’t that the narrative was unclear or that I was confused. It just felt pretentious, as if the author were saying he was above all things mundane. And if you believe his quote at the beginning of this post, you’d say he was just being a….well, you fill in the blank.

McCarthy calls quotes “Weird little marks” and once said: “I believe in periods, in capitals, in the occasional comma, and that’s it.” After a while, I didn’t care about the punctuation. The story sped along, the characters captured me by the throat and by the heart.

Then there’s the other side of the coin — guys like William Faulkner, who could have used some judicious punctuating. Check out this passage from The Sound and the Fury:

My God the cigar what would your mother say if she found a blister on her mantel just in time too look here Quentin we’re about to do something we’ll both regret I like you liked you as soon as I saw you I says he must be …

Faulkner’s advice to tackling it? “Read it four times.” Gee, thanks, Bill.

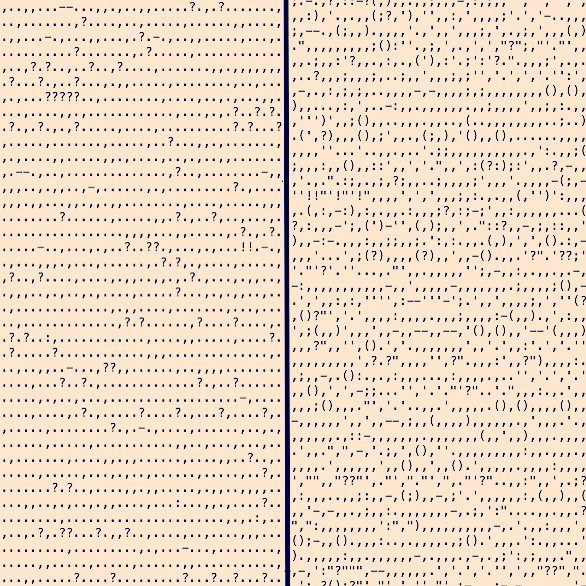

I read an interesting post about this subject recently. The author Adam J. Calhoun suggests that simple punctuation goes a long ways toward sign-posting a novelist’s style. He compared passages from two of his favorite novels — McCarthy’s Blood Meridian and Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom! taking out all punctuation marks. Guess which book is which?

Says Calhoun: “Yes, the contrast is stark. But the wild mix of symbols can be beautiful, too. Look at the array of dots and dashes above! This Morse code is both meaningless and yet so meaningful. We can look and say: brief sentence; description; shorter description; action; action; action.”

And we can easily tell, just by the choice of punctuation, who wrote what.

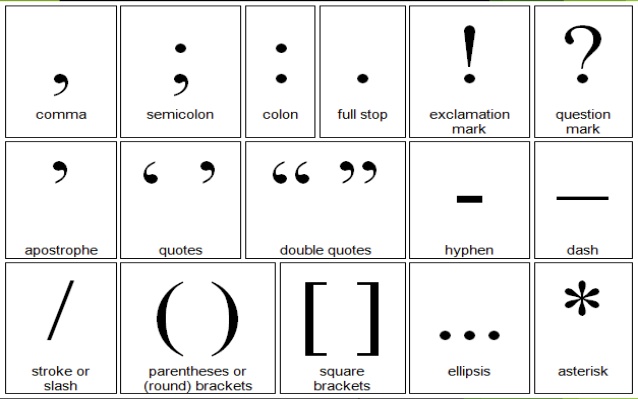

So what does this mean for us mere mortals? I think most of us, myself included, don’t think too much about the punctuation we use. We know the basics of periods, question marks and quotation marks. We get a little confused about commas, and when to use dashes or ellipses. And we have banished the poor semi-colon to the grammar dungeon. We put in the symbols quickly and race on, saving our tsuris for the big issues of plot, characterization and theme. But I’d like to suggest today that we give more thought to these fellows:

The symbols we chose to insert among our words can go a long way to establishing not just our unique styles but the kinds of emotions we want our readers to feel. Some of us, especially those working in neo-noir, favor a style a la Hemingway — short sentences with workmanlike punctuation. If you read “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” you see a story rendered with only quote marks, question marks and periods. Oddly, the only comma is in the title. Maybe Hemingway was taking the advice of his friend Gertrude Stein who called the comma “a poor period that lets you stop and take a breath but if you want to take a breath you ought to know yourself that you want to take a breath.”

Some of us, especially those working in historicals, favor a lusher style and will sow commas to force the reader to pause and take in the scenery. Look at this passage:

He moved to his left, circling around the trampled area, stopping every couple of steps to examine what lay before him. He was almost diagonally opposite the point where he’d left the path when he saw it. Just in front of him and to the right, where was a dark patch on the startling white bark of a birch tree. Irresistibly drawn, he moved closer.

The blood had dried long since. But adhering to it, unmistakably, were a dozen strands of bright blonde hair. And on the ground next to the tree, a horn toggle with a scrap of material still attached.

That’s from Val McDermid’s A Place of Execution. Notice the liberal use of commas. McDermid wants the reader to slow down and absorb, along with her detective, every awful detail of the death scene. When you want your reader to slow down, commas are your friends.

What about the dash and its cousin the ellipses? I use both often in my work. In my mind, a dash signals an abruption interruption in thought or speech. An ellipses, in contrast, is a trailing off of the same. Here’s Reed Farrel Coleman in Redemption Street:

It took many years for my mom not to imagine her only daughter burning up alive. Can you imagine the tortuous second-guessing my parents put themselves through? If they hadn’t let he go. If they had forced her to go to a better hotel. If…If…If…

I’m a big fan of the em dash. It is a useful little bugger. It can indicate an interruption:

“The commissioner phoned the home office. The home office phone the Circus — “

“And you phoned me,” Smiley said.

Notice that John Le Carre did not feel the need to write “Smiley interrupted.” The dash did the work.

Le Carre also uses dashes in mid-narrative to inject parenthetical info. An example of this is the last part of the sentence: “I had steak last night for dinner (and it was really good!).” But no character thinks or speaks in ( ) so the dash is an effective substitute. Here’s Le Carre again:

The only link to Hamburg he might have pleaded — if he had afterward attempted the connection, which he did not — was in the Parnassian field of German baroque poetry.

Again, depending on your style, a parenthetical dash might be good. Or it can look fussy. And be aware it tends to slow down your narrative. There’s an Emily Dickinson poem called The Brain Is Wider Than the Sky that is stuffed with em dashes.

The Brain—is wider than the Sky—

For—put them side by side—

The one the other will contain

With ease—and you—beside—

The Brain is deeper than the sea—

For—hold them—Blue to Blue—

The one the other will absorb—

As sponges—Buckets—do—

The Brain is just the weight of God—

For—Heft them—Pound for Pound—

And they will differ—if they do—

As Syllable from Sound—

I confess I don’t understand the usage here. Poetry is a different animal altogether. I just threw it in here because it’s interesting.

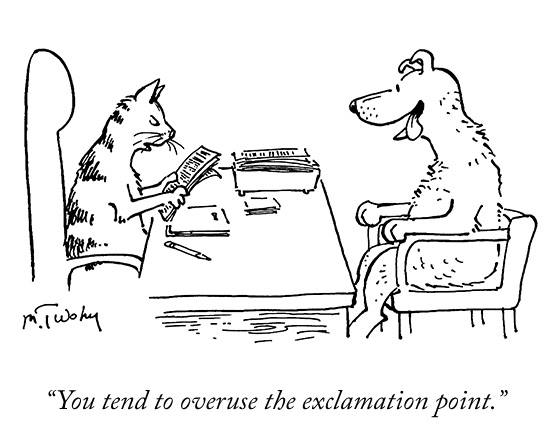

Okay, we need a word about exclamation marks. I know, I know…seems a simple matter. But I’m surprised at how often I see it misused. Many writers throw them in thoughtlessly, as if trying to wring emotion from readers. In my mind, exclamation marks are like adverbs. If you need one, your dialogue is probably flaccid. Think of it as a potent spice — in the right place, it does wonders for your word stew. Trust me!

And what about the colon? Does it have a place in our genre? I’ve seen it used correctly, but it never feels authentic to me, given our love affair with intimate point of view these days. It feels outdated. And try as I might, I couldn’t find one example of its use in a novel after 1890. What about if you need to list things, as in this example, which I made up:

Jack Reacher was afraid of only three things: women wearing red stilettos, men in turbans, and snakes.

Or this:

Jack Reacher was afraid of only three things — women wearing red stilettos, men in turbans, and snakes.

The second one feels right to me. I say if your colon is acting up, try a dash.

Which brings us, alas, to the dreaded semi-colon. We’ve thrashed this topic to death, and most of us now agree it has no place in modern fiction. (Please use the comment section to argue your case otherwise). I never use one. I don’t like seeing them in print. There, I’ve said it. So sue me. But I will end my post with one of my favorite openings of a novel:

No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against the hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.”

That’s the opening of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House. I just love every word of this paragraph. I don’t care that there are three semi-colons and enough commas to choke a ghost. As Random House copy chief Benjamin Dreyer explains: “Jackson uses them, beautifully, to hold her sentences tightly together…Commas, semicolons, periods: This is how the prose breathes.”

So I guess the bottom line is to know thyself and thine style. Be aware of what punctuation marks can do to slow or speed up your story. Be attentive to the emotions these symbols can impart in readers. And that, friends, is how we end. Not with whimpering ellipses, not with a startling dash, and certainly not with a barking exclamation pointer. With a simple full-stop period.

I’ve spent 12 years on social media. *cringe* In that time I like to think I’ve learned a thing or two. That’s not to say my social media presence is 100% perfect. Far from it. I am a flawed human. The trick is knowing where and how you went wrong, so you don’t repeat the mistake and destroy your social media platform.

I’ve spent 12 years on social media. *cringe* In that time I like to think I’ve learned a thing or two. That’s not to say my social media presence is 100% perfect. Far from it. I am a flawed human. The trick is knowing where and how you went wrong, so you don’t repeat the mistake and destroy your social media platform.

Happy Easter. Happy Passover. Happy Sunday. Whether you worship, play, or simply lounge around, may you feel renewed and refreshed this day.

Happy Easter. Happy Passover. Happy Sunday. Whether you worship, play, or simply lounge around, may you feel renewed and refreshed this day.

By Elaine Viets

By Elaine Viets But what about ordinary writers? Should we read our own work?

But what about ordinary writers? Should we read our own work?

When I finished, I needed to put my tongue in a sling. My sore, scratchy throat took weeks to recover.

When I finished, I needed to put my tongue in a sling. My sore, scratchy throat took weeks to recover.

Edgar Allen Poe’s short story The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841) is generally considered to be the first modern murder mystery, and its detective, Auguste C. Dupin, the first fictional detective. There was no monkey business in Dupin’s analysis of the horrific crime and identification of the murderer.

Edgar Allen Poe’s short story The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841) is generally considered to be the first modern murder mystery, and its detective, Auguste C. Dupin, the first fictional detective. There was no monkey business in Dupin’s analysis of the horrific crime and identification of the murderer. Wilkie Collins was a contemporary of Charles Dickens and is credited with the first novel-length mystery, The Woman in White (1859). The book doesn’t just stop at murder – it also touches on insanity, social stratification, false identity, and a few other themes. Collins considered the book his best work and instructed that the phrase “Author of The Woman in White” be inscribed on his tombstone. He also lays claim to the first detective novel, The Moonstone (1868).

Wilkie Collins was a contemporary of Charles Dickens and is credited with the first novel-length mystery, The Woman in White (1859). The book doesn’t just stop at murder – it also touches on insanity, social stratification, false identity, and a few other themes. Collins considered the book his best work and instructed that the phrase “Author of The Woman in White” be inscribed on his tombstone. He also lays claim to the first detective novel, The Moonstone (1868). Arthur Conan Doyle published A Study in Scarlet, the first story featuring Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, in 1887. In total, Doyle wrote 56 short stories and four novels featuring the famous detective. When he killed off Sherlock Holmes in The Final Problem (1893), the public outcry was so severe, Doyle had to bring him back in later works.

Arthur Conan Doyle published A Study in Scarlet, the first story featuring Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, in 1887. In total, Doyle wrote 56 short stories and four novels featuring the famous detective. When he killed off Sherlock Holmes in The Final Problem (1893), the public outcry was so severe, Doyle had to bring him back in later works. Maurice Leblanc began a mystery series in 1905 featuring the gentleman thief Arsene Lupin, a character who’s been described as a French version of Sherlock Holmes. In all, Leblanc wrote 17 novels and 39 novellas with Lupin as hero. Check out

Maurice Leblanc began a mystery series in 1905 featuring the gentleman thief Arsene Lupin, a character who’s been described as a French version of Sherlock Holmes. In all, Leblanc wrote 17 novels and 39 novellas with Lupin as hero. Check out  G.K. Chesterton is credited with creating the cozy mystery genre with a series of 53 short stories begun in 1910 featuring the Roman Catholic priest and amateur detective, Father Brown, who uses his intuitive understanding of human nature to solve crimes. The character was so popular, it inspired the Father Brown TV series that began in 2013.

G.K. Chesterton is credited with creating the cozy mystery genre with a series of 53 short stories begun in 1910 featuring the Roman Catholic priest and amateur detective, Father Brown, who uses his intuitive understanding of human nature to solve crimes. The character was so popular, it inspired the Father Brown TV series that began in 2013. The Thirty-nine Steps (1915) by Scottish author John Buchan was the first of five novels featuring Richard Hannay. a man on the run who had been unjustly accused of murder. There are a couple of movie versions of The Thirty-nine Steps, but my favorite is the 1935 Hitchcock film starring Robert Donat.

The Thirty-nine Steps (1915) by Scottish author John Buchan was the first of five novels featuring Richard Hannay. a man on the run who had been unjustly accused of murder. There are a couple of movie versions of The Thirty-nine Steps, but my favorite is the 1935 Hitchcock film starring Robert Donat. Cozy mysteries became very popular in the 1920’s and 30’s with several great British authors. Agatha Christie’s first novel The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920), featured Hercule Poirot, a sleuth who used his “little gray cells” to solve mysteries. Poirot showed up in 33 novels and over 50 short stories. (I will have much more to say about Dame Agatha in a future post.)

Cozy mysteries became very popular in the 1920’s and 30’s with several great British authors. Agatha Christie’s first novel The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920), featured Hercule Poirot, a sleuth who used his “little gray cells” to solve mysteries. Poirot showed up in 33 novels and over 50 short stories. (I will have much more to say about Dame Agatha in a future post.)

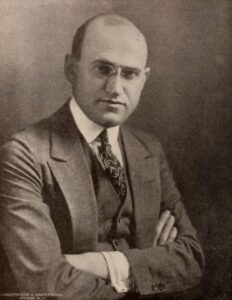

Hardboiled detective fiction became popular in the 1920’s and extended through the 20th century. Dashiel Hammett became famous for his character Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon (1929). He also created the sophisticated couple Nick and Nora Charles in The Thin Man (1933). Strangely, Hammett wrote his final novel more than 25 years before his death. Why he stopped writing fiction is something of a mystery in itself.

Hardboiled detective fiction became popular in the 1920’s and extended through the 20th century. Dashiel Hammett became famous for his character Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon (1929). He also created the sophisticated couple Nick and Nora Charles in The Thin Man (1933). Strangely, Hammett wrote his final novel more than 25 years before his death. Why he stopped writing fiction is something of a mystery in itself. Raymond Chandler was forty-four years old when he began his journey as an author. His first novel, The Big Sleep (1939), introduced the world to private detective Philip Marlowe. In addition to his short stories, Chandler wrote seven novels, all with Marlowe as the hero. His prose is widely admired and his use of similes is famous. Here’s an example from The Big Sleep: “The General spoke again, slowly, using his strength as carefully as an out-of-work showgirl uses her last good pair of stockings.”

Raymond Chandler was forty-four years old when he began his journey as an author. His first novel, The Big Sleep (1939), introduced the world to private detective Philip Marlowe. In addition to his short stories, Chandler wrote seven novels, all with Marlowe as the hero. His prose is widely admired and his use of similes is famous. Here’s an example from The Big Sleep: “The General spoke again, slowly, using his strength as carefully as an out-of-work showgirl uses her last good pair of stockings.” “Once upon a time,” I told my two oldest grandboys, “there were two baby monsters. One was green and one was blue. They lived in a cave with their mom and dad…”

“Once upon a time,” I told my two oldest grandboys, “there were two baby monsters. One was green and one was blue. They lived in a cave with their mom and dad…”