“If you write properly, you shouldn’t have to punctuate.” — Cormac McCarthy.

“If you write properly, you shouldn’t have to punctuate.” — Cormac McCarthy.

By PJ Parrish

I guess when you win the Pulitzer Prize for literature, you can do whatever you want. I read McCarthy’s The Road years ago. There are no quote marks to set off the dialogue. There are no commas or question marks. There are periods, but even they are sparse. McCarthy’s pages look as bleak and barren as the story’s apocalyptic landscape.

When I first started the book, the lack of punctuation annoyed me. It wasn’t that the narrative was unclear or that I was confused. It just felt pretentious, as if the author were saying he was above all things mundane. And if you believe his quote at the beginning of this post, you’d say he was just being a….well, you fill in the blank.

McCarthy calls quotes “Weird little marks” and once said: “I believe in periods, in capitals, in the occasional comma, and that’s it.” After a while, I didn’t care about the punctuation. The story sped along, the characters captured me by the throat and by the heart.

Then there’s the other side of the coin — guys like William Faulkner, who could have used some judicious punctuating. Check out this passage from The Sound and the Fury:

My God the cigar what would your mother say if she found a blister on her mantel just in time too look here Quentin we’re about to do something we’ll both regret I like you liked you as soon as I saw you I says he must be …

Faulkner’s advice to tackling it? “Read it four times.” Gee, thanks, Bill.

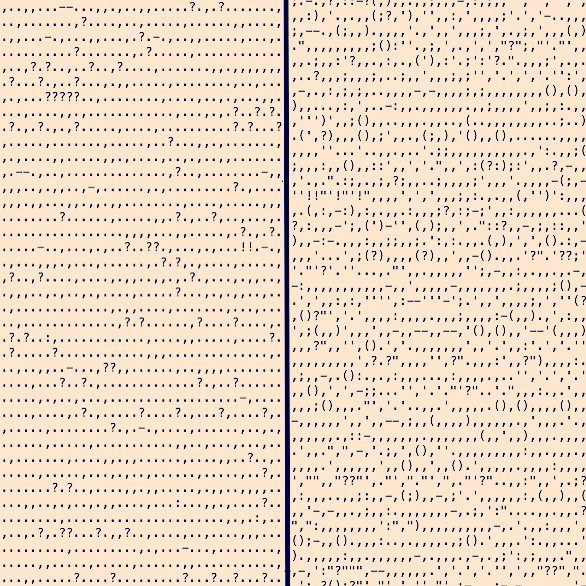

I read an interesting post about this subject recently. The author Adam J. Calhoun suggests that simple punctuation goes a long ways toward sign-posting a novelist’s style. He compared passages from two of his favorite novels — McCarthy’s Blood Meridian and Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom! taking out all punctuation marks. Guess which book is which?

Says Calhoun: “Yes, the contrast is stark. But the wild mix of symbols can be beautiful, too. Look at the array of dots and dashes above! This Morse code is both meaningless and yet so meaningful. We can look and say: brief sentence; description; shorter description; action; action; action.”

And we can easily tell, just by the choice of punctuation, who wrote what.

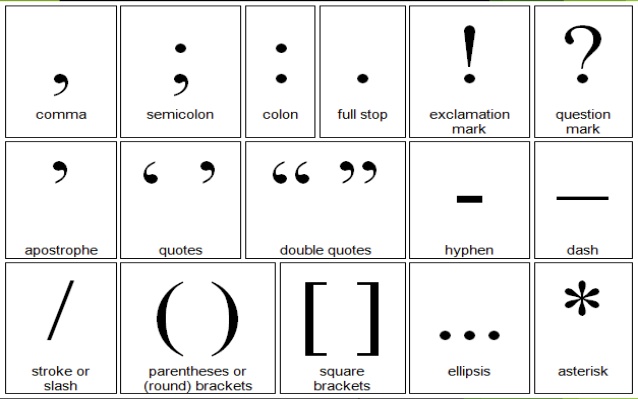

So what does this mean for us mere mortals? I think most of us, myself included, don’t think too much about the punctuation we use. We know the basics of periods, question marks and quotation marks. We get a little confused about commas, and when to use dashes or ellipses. And we have banished the poor semi-colon to the grammar dungeon. We put in the symbols quickly and race on, saving our tsuris for the big issues of plot, characterization and theme. But I’d like to suggest today that we give more thought to these fellows:

The symbols we chose to insert among our words can go a long way to establishing not just our unique styles but the kinds of emotions we want our readers to feel. Some of us, especially those working in neo-noir, favor a style a la Hemingway — short sentences with workmanlike punctuation. If you read “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” you see a story rendered with only quote marks, question marks and periods. Oddly, the only comma is in the title. Maybe Hemingway was taking the advice of his friend Gertrude Stein who called the comma “a poor period that lets you stop and take a breath but if you want to take a breath you ought to know yourself that you want to take a breath.”

Some of us, especially those working in historicals, favor a lusher style and will sow commas to force the reader to pause and take in the scenery. Look at this passage:

He moved to his left, circling around the trampled area, stopping every couple of steps to examine what lay before him. He was almost diagonally opposite the point where he’d left the path when he saw it. Just in front of him and to the right, where was a dark patch on the startling white bark of a birch tree. Irresistibly drawn, he moved closer.

The blood had dried long since. But adhering to it, unmistakably, were a dozen strands of bright blonde hair. And on the ground next to the tree, a horn toggle with a scrap of material still attached.

That’s from Val McDermid’s A Place of Execution. Notice the liberal use of commas. McDermid wants the reader to slow down and absorb, along with her detective, every awful detail of the death scene. When you want your reader to slow down, commas are your friends.

What about the dash and its cousin the ellipses? I use both often in my work. In my mind, a dash signals an abruption interruption in thought or speech. An ellipses, in contrast, is a trailing off of the same. Here’s Reed Farrel Coleman in Redemption Street:

It took many years for my mom not to imagine her only daughter burning up alive. Can you imagine the tortuous second-guessing my parents put themselves through? If they hadn’t let he go. If they had forced her to go to a better hotel. If…If…If…

I’m a big fan of the em dash. It is a useful little bugger. It can indicate an interruption:

“The commissioner phoned the home office. The home office phone the Circus — “

“And you phoned me,” Smiley said.

Notice that John Le Carre did not feel the need to write “Smiley interrupted.” The dash did the work.

Le Carre also uses dashes in mid-narrative to inject parenthetical info. An example of this is the last part of the sentence: “I had steak last night for dinner (and it was really good!).” But no character thinks or speaks in ( ) so the dash is an effective substitute. Here’s Le Carre again:

The only link to Hamburg he might have pleaded — if he had afterward attempted the connection, which he did not — was in the Parnassian field of German baroque poetry.

Again, depending on your style, a parenthetical dash might be good. Or it can look fussy. And be aware it tends to slow down your narrative. There’s an Emily Dickinson poem called The Brain Is Wider Than the Sky that is stuffed with em dashes.

The Brain—is wider than the Sky—

For—put them side by side—

The one the other will contain

With ease—and you—beside—

The Brain is deeper than the sea—

For—hold them—Blue to Blue—

The one the other will absorb—

As sponges—Buckets—do—

The Brain is just the weight of God—

For—Heft them—Pound for Pound—

And they will differ—if they do—

As Syllable from Sound—

I confess I don’t understand the usage here. Poetry is a different animal altogether. I just threw it in here because it’s interesting.

Okay, we need a word about exclamation marks. I know, I know…seems a simple matter. But I’m surprised at how often I see it misused. Many writers throw them in thoughtlessly, as if trying to wring emotion from readers. In my mind, exclamation marks are like adverbs. If you need one, your dialogue is probably flaccid. Think of it as a potent spice — in the right place, it does wonders for your word stew. Trust me!

And what about the colon? Does it have a place in our genre? I’ve seen it used correctly, but it never feels authentic to me, given our love affair with intimate point of view these days. It feels outdated. And try as I might, I couldn’t find one example of its use in a novel after 1890. What about if you need to list things, as in this example, which I made up:

Jack Reacher was afraid of only three things: women wearing red stilettos, men in turbans, and snakes.

Or this:

Jack Reacher was afraid of only three things — women wearing red stilettos, men in turbans, and snakes.

The second one feels right to me. I say if your colon is acting up, try a dash.

Which brings us, alas, to the dreaded semi-colon. We’ve thrashed this topic to death, and most of us now agree it has no place in modern fiction. (Please use the comment section to argue your case otherwise). I never use one. I don’t like seeing them in print. There, I’ve said it. So sue me. But I will end my post with one of my favorite openings of a novel:

No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against the hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.”

That’s the opening of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House. I just love every word of this paragraph. I don’t care that there are three semi-colons and enough commas to choke a ghost. As Random House copy chief Benjamin Dreyer explains: “Jackson uses them, beautifully, to hold her sentences tightly together…Commas, semicolons, periods: This is how the prose breathes.”

So I guess the bottom line is to know thyself and thine style. Be aware of what punctuation marks can do to slow or speed up your story. Be attentive to the emotions these symbols can impart in readers. And that, friends, is how we end. Not with whimpering ellipses, not with a startling dash, and certainly not with a barking exclamation pointer. With a simple full-stop period.

Like you, Kris, I prefer the em dash for parentheticals. But Stephen King, I note, doesn’t hesitate to use actual parentheses. It feels a bit like author intrusion, but I think that’s his intent. He’s crooking his finger at the reader to lean in closer, as if telling the story around a campfire. He can get away with it because of his evident joy in telling the tale.

As for semi-colons: “Here is a lesson in creative writing. First rule: Do not use semicolons … All they do is show you’ve been to college.” – Kurt Vonnegut

I didn’t realize that King used ( ) until I went and checked one of his books. I see your point about the crooking finger….a good analogy. And yeah, it does signal a kind of joy in storytelling.

I thought of King, too. Hate the use of parenthesis in fiction.

I love em dashes, and used them too much at one point. Em dash splice.

I agree with most of what you say, and it’s interesting to consider punctuation. The one thing that trips me up from time to time is the semicolon. Every so often, I run into the sentence that needs just a quick paus, not the two count pause of the period, but the one count of the comma. But each side of the comma is a complete sentence and adding a conjunction will throw off the rhythm. That’s when I may throw in the semicolon and hope my (currently nonexistent) copyeditor will tell me what to do. Usually comes when two observations of scenery or revelation come one right after the other.

I can understand your need to employ the occasional semi-colon. As you say, it’s a matter of individual style and taste and you have to know yourself as a writer to decide. It never works for me. 🙂

Wonderful post, Kris. Great stuff.

In movies and the theater, the music–its phrasing, volume, and tempo–have great control in setting the emotion for the audience. As writers, we have nothing but our Morse code of words and punctuation to accomplish the same. It seems to me that we should use them to their fullest potential. One good way to “feel” the effect we are trying to create is to listen to the rhythm with text to speech, or someone else reading the passage to us.

In defense of the em dash, that’s the way we think and communicate, Half way through a thought, we feel the need to insert an explanation we should have expressed earlier.

Thanks for making us think. In this age of short attention spans and the desire to see the narrative acted out on the screen, this may be more important than ever before.

Hope your day is filled with good exclamation points, and no question marks.

That’s an excellent comparison, Steve, that musicians have various “marks” to denote rhythm and speed. Much as we do in our prose. I remember when I first started taking piano lessons and I used to drive my poor teacher crazy before I didn’t pay close enough attention to various notations on a musical piece…I was always “feeling” my way along. I still have the antique metronome she gave me.

Likewise, dancers are taught to count beats and strictly adhere to the musical impulse. But the best dancers find a way to make their movements “fit” into a musical equation. It’s a matter of phrasing and what makes a dancer artistic rather than mundane.

I always think of Sinatra and how he bent and played with a musical phrase to give it his unique imprint. He colored outside the lines.

And you make me think that I have another post in me just about the “rhythm” of good writing.

I look forward to it!

Interesting as I read this post I felt most at home with the Val McDermid example.

RE: Colons in fiction–now you’ve got my brain filled with this random bit of info so I’m going to have to do a search in a couple of my manuscripts & see if I’ve ever had occasion to use a colon. LOL! It definitely doesn’t ‘feel’ like a fiction punctuation mark.

That’s a good way to think of it — that it doesn’t “feel” like a FICTION punctuation. Semi-colons are fine in more prosaic writing, imho.

I say if your colon is acting up, try a dash.

A dash of what? Fiber?

OK, had to check. Based on a large sample, my magnum opus, “The Perils of Tenirax: Mad Poet of Zaragoza,” has not only about 120 semicolons in the text, it has one in the title as a warning to readers: 𝕳𝖊𝖗𝖊 𝖙𝖍𝖊𝖗𝖊 𝖇𝖊 𝖈𝖔𝖑𝖔𝖓𝖘.

That’s one colon about every 2.5 typed pages.

I adore the em dash. It’s handy and useful. I never insert semi-colons, but my line editor does on occasion. Even if I convince the editor to remove the little bugger, the proofreader might stick it back in. Ugh. Drives me crazy.

Gorgeous writing in the last passage you quoted. Thank you, Kris(!). 😉

IMHO, Kris, colons and semicolons have their place (sometimes) in non-fiction but not in fiction – especially not in dialogue! Commas, however, have their place. The trick is figuring out where. Thanks for the piece… and enjoy your day!!!

Thank you!!!!! 🙂

I never suggest a fiction writer uses semi-colons or colons in narrative, but, but, when narrative or dialog is filtered through certain types of people, they can be forgiven. One of my characters was a university English professor from a very posh Southern family. His dialog was littered with semi-colons because he was a pretentious prick.

Thanks, Kris, enjoyed this immensely. I’ve gotten so that when I’m reading fiction, a semicolon is like a flashing neon sign blaring “Warning! Go back!”

It stops me in my tracks. 🤡

Great discussion.

I see punctuation as a secret code between the writer and reader — a device to embellish the story without using words. Symbolism in the raw.

I misread this sentence about Shirley Jackson’s work, “Jackson uses them, beautifully, to hold her sentences tightly together…Commas, semicolons, periods: This is how the prose breathes.” I thought it said, “to hold her sentences lightly together.” I think I like my mistaken reading better!

Expel me from the club if you like, but I also like the lowly semi-colon; probably just because I always root for the underdog.

You got me curious, Kay, about how the semi-colon came about. We now have someone officially to blame for it — Aldus Manutius. From the Paris Review:

The semicolon was born in Venice in 1494. It was meant to signify a pause of a length somewhere between that of the comma and that of the colon. It was born into a time period of writerly experimentation and invention, when there were no punctuation rules, and readers created and discarded novel punctuation marks regularly. (Yikes!) The Italian humanists put a premium on eloquence and excellence in writing, and they called for the study and retranscription of Greek and Roman classical texts as a way to effect a “cultural rebirth” after the gloomy Middle Ages.

So the semi-colon was born because no one bothered with punctuation at all. Geez…

Aldus Manutius! I should have known. He’s one of my heroes—I even did a TKZ article on Manutius and his motto “Festina Lente” a while back:

http://killzoneblog.com/2021/12/festina-lente.html

If it was good enough for Aldus …

I’m impressed you know of him!

Fantastic post, Kris. I do love my commas, sometimes too much, as my copy editor and ProWriting Aid both remind me. I try to avoid semi-colons as much as possible, but on rare occasions in my fiction, they seem necessary, unless I restructure the sentence or paragraph. And I’m a traditionalist when it comes to using quote marks for dialogue. Saying that here probably means my subconscious is going to furnish me with a flash fiction piece that doesn’t use them. Fine, but I’ll insist on commas.

Thanks for this great discussion. Have a wonderful Tuesday!

I love exclamation points! Life should be exciting, never stuffy.

I.hate.periods.between.every.word.

Ha! This whole post was inspired by the cartoon. Dogs “talk” in exclamation points. Cats? Ellipses, for sure, with an occasional ( ) because they always have hidden agendas.

Cats are masters of subtext. Alas, it’s lost on cat owners.

Young writers love them, too. I remind them that all those exclamation points make their prose sound like a pre-teen’s diary.

Or a Facebook screed.

The Faulkner quote is stream of consciousness. The novel has three different narrators/viewpoint characters and three different styles. Quentin’s is all stream of consciousness as he’s getting ready to kill himself.

I’ve always thought steam of consciousness and the lack of punctuation is mainly pretentious nonsense, but Faulkner made a good use of it for Quentin. For us regular popular genre writers, it would be an interesting choice if we were writing a character on drugs, drunk, or dying. Maybe a dream. Or demented. (I’ve just created the Five “D” Reasons to use stream of consciousness. )

Much of Faulkner’s prose was very formal King James Bible influenced Southern narrative. I don’t recall the semicolon usage, but I image there was a lot.

For those who didn’t spend half of their college life reading Southern Gothic fiction, a good example of this style is Martin Luther King, Jr’s, speeches.

Thanks for clarifying that, Marilynn. I guess I still am in a bad mood having had to read a lot of Faulkner as a lit major. I read Proust to

just to cleanse the palate. j/k.

I slogged through a book with no quotation marks. 701 pages of it, and me trying to separate narrative from internal monologue from dialogue. Very minimal punctuation otherwise, as well.

And too many similar names, and jumping back and forth in time. I still ask myself why I finished it.

If something might pull a reader out of a story, LEAVE IT OUT.

Yeah, similar names are another bete noire for me…no reason for it. Argh!

Yes, I critiqued a play once with Kenny, Karen & Courtney, and Davis & Don. Hoo, boy.

I never use the semicolon, but my editor puts one in every now and then. I love the em dash and ellipses…if you’ve ever read my comments here, you already know that.

Since I’m from Mississippi, I felt duty-bound to read Faulkner. That was when I thought I should always finish a book I’ve started. I think he broke me of that habit. Although I did like some of his short stories…or would’ve if they’d been short.

Hall Phillips also lived in the same town I do and his writing is literary and I loved it. The Bitterweed Path was great.

Good post, Kris. It took me a while to figure out how to use the EM dash within dialogue, but I now ride that beast effortlessly. (BTW, where’s the EN dash? Used for numbers and ranges.)

And because I’m now writing stories with spoken Spanish, the inverted question mark is part of my punctuation arsenal.