What was the worst fashion choice you ever made?

(I really did have a polyester suit. Oh, the horror.)

By Debbie Burke

This saying has been around for centuries, variously attributed to Benjamin Franklin and Edgar Allen Poe.

Today, thanks to Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML), you can no longer believe anything you hear or see.

That’s because what your ears hear and what your eyes see could be a DEEPFAKE.

What is a deepfake? Wikipedia says:

…synthetic media in which a person in an existing image or video is replaced with someone else’s likeness. While the act of faking content is not new, deepfakes leverage powerful techniques from machine learning and artificial intelligence to manipulate or generate visual and audio content with a high potential to deceive. The main machine learning methods used to create deepfakes are based on deep learning and involve training generative neural network architectures, such as autoencoders or generative adversarial networks (GANs).

Deepfakes have garnered widespread attention for their uses in creating child sexual abuse material, celebrity pornographic videos, revenge porn, fake news, hoaxes, bullying, and financial fraud. This has elicited responses from both industry and government to detect and limit their use.

I wrote about AI three years ago. Since then, technology has progressed at warp speed.

The first recognized crime that used deepfake technology occurred in 2019 with voice impersonation.

The CEO of an energy business in the UK received an urgent call from his boss, an executive at the firm’s German parent company. The CEO recognized his boss’s voice…or so he thought. He was instructed to immediately transfer $243,000 to pay a Hungarian supplier. He followed orders and transferred the money.

The funds went into a Hungarian account but then disappeared to Mexico. According to the company’s insurer, Euler Hermes, the money was never recovered.

To pull off the heist, cybercriminals used AI voice-spoofing software that perfectly mimicked the boss’s tone, speech inflections, and slight German accent.

Such spoofing extends to video deceptions that are chilling. The accuracy of movement and gesture renders the imposter clone indistinguishable from the real person. Some research shows a fake face can more believable than the real one.

Security safeguards like voice authentication and facial recognition are no longer reliable.

A November 2020 study by Trend Micro, Europol, and United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute concludes:

The Crime-as-a-Service (CaaS) business model, which allows non-technologically savvy criminals to procure technical tools and services in the digital underground that allow them to extend their attack capacity and sophistication, further increases the potential for new technologies such as AI to be abused by criminals and become a driver of crime.

We believe that on the basis of technological trends and developments, future uses or abuses could become present realities in the not-too-distant future.

The not-too-distant future they mentioned in 2020 is here today. A person no longer needs to be a sophisticated expert to create fake video and audio recordings of real people that defy detection.

In the following YouTube, a man created a fake image of himself to fool coworkers into believing they were video-chatting with the real person. It’s long—more than 18 minutes—but watching even a few minutes demonstrates how simple the process is.

Consider the implications:

What if you could appear to be in one place but actually be somewhere else? Criminals can create their own convincing alibis.

If corrupt law enforcement, government entities, or political enemies want to frame or discredit someone, they manufacture video evidence that shows the person engaged in criminal or abhorrent behavior.

Imagine the mischief terrorists could cause by putting words in the mouths of world leaders. Here are some examples: https://www.cnn.com/interactive/2019/01/business/pentagons-race-against-deepfakes/

Deepfakes could change history, creating events that never actually happened. Check out this example made at MIT of a fake Richard Nixon delivering a fake 1969 speech to mourn astronauts who supposedly perished on the moon. Fast forward to 4:18.

How was this software developed?

It arose from Machine Learning (ML). The process involves pitting computers against one another to see which one most accurately reproduces expressions, gestures, and voices from real people. The more they compete with each other, the better they learn, and the more authentic their fakes become.

A fanciful imagining of a contest might sound like this.

Computer A: “Hey, look at this Jack Nicholson eyebrow quirk I mastered.”

Computer B: “That’s nothing. Samuel L. Jackson’s nostril flare is much harder. Bet yours can’t top mine.”

Computer A: “Oh yeah? Check out how I made Margaret Thatcher to cross her legs just like Sharon Stone.”

The Europol study further outlined ways that deepfakes could be used for malicious or criminal purposes:

Destroying the image and credibility of an individual,

Harassing or humiliating individuals online,

Perpetrating extortion and fraud,

Facilitating document fraud,

Falsifying online identities and fooling KYC [Know Your Customer] mechanisms,

Falsifying or manipulating electronic evidence for criminal justice investigations,

Disrupting financial markets,

Distributing disinformation and manipulating public opinion,

Inciting acts of violence toward minority groups,

Supporting the narratives of extremist or even terrorist groups, and

Stoking social unrest and political polarization

In the era of deepfakes, can video/audio evidence ever be trusted again?

~~~

A big Thank You to TKZ regular K.S. Ferguson who suggested the idea for this post and provided sources.

~~~

TKZers: Can you name books, short stories, or films that incorporate deepfakes in the plot? Feel free to include sci-fi/fantasy from the past where the concept is used before it existed in real life.

Please put on your criminal hat and suggest fictional ways a bad guy could take advantage of deepfakes.

Or put on your detective hat and offer solutions to thwart the evil-doer.

~~~

Debbie Burke’s characters are not created by Artificial Intelligence but rather by her real imagination.

Please check out her latest Tawny Lindholm Thriller.

Until Proven Guilty is for sale at major booksellers here.

Speed Dating and Swag

Terry Odell

I’m hardly a marketing guru—it’s the least favorite part of writing for me—but I made some observations at the Left Coast Crime conference and thought I’d share them.

I’m hardly a marketing guru—it’s the least favorite part of writing for me—but I made some observations at the Left Coast Crime conference and thought I’d share them.

As I mentioned earlier, Left Coast Crime is a reader-focused conference, which means it’s a place where readers come to meet authors, both familiar and new. It’s an ideal opportunity for us lesser-knowns to make connections.

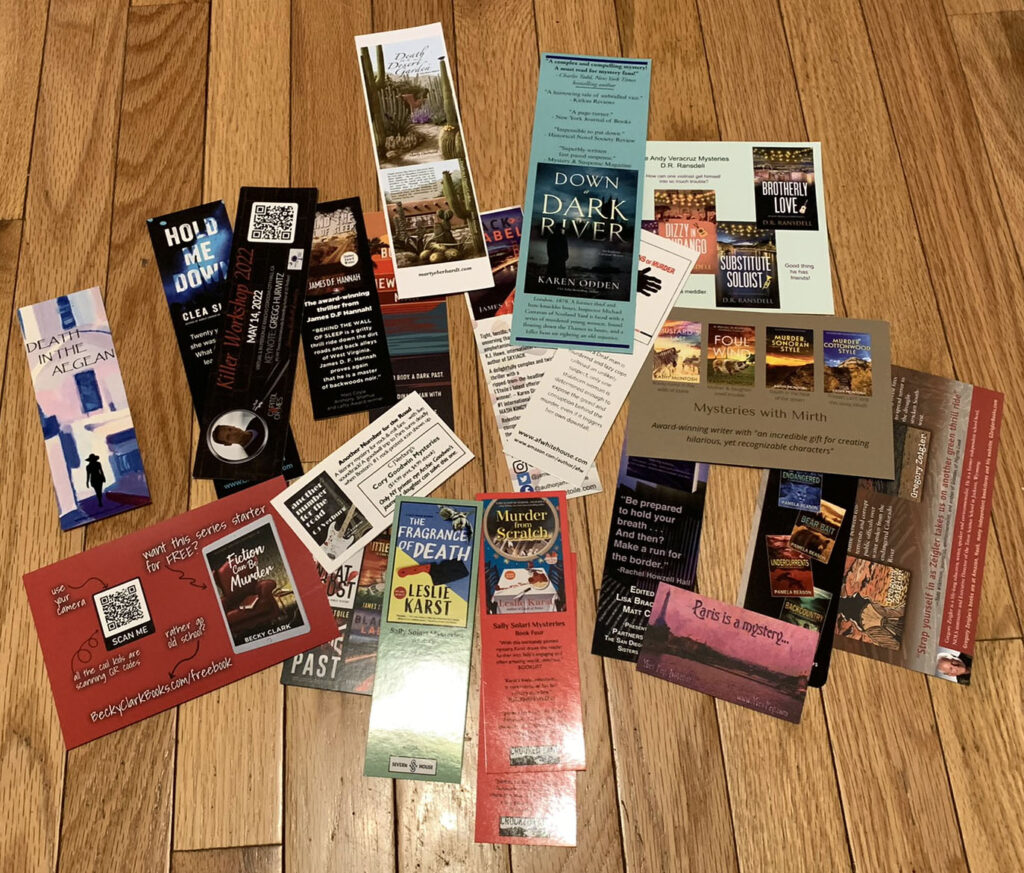

Any writing conference I’ve been to, whether reader or author/craft focused, has a giveaway table where authors leave freebies—swag. With several hundred authors vying for attention, it’s important that these items entice readers (and authors are readers, too) to pick them up. Anything left on the tables after the conference closes will be trashed by the hotel staff, so you might be carting home a lot of what you brought.

The most common items are paper goods. Bookmarks dominate. How effective are they? With so many people using e-readers these days, they don’t serve the same purpose—something that the reader will encounter every time they pick up their book.

I think bookmarks are more effective when handed our personally, like a business card, but even then, they are likely to end up in the hotel room wastebasket. I stopped getting bookmarks made years ago, but I do have business cards with QR codes to my website and Facebook Author Page on the back.

I think bookmarks are more effective when handed our personally, like a business card, but even then, they are likely to end up in the hotel room wastebasket. I stopped getting bookmarks made years ago, but I do have business cards with QR codes to my website and Facebook Author Page on the back.

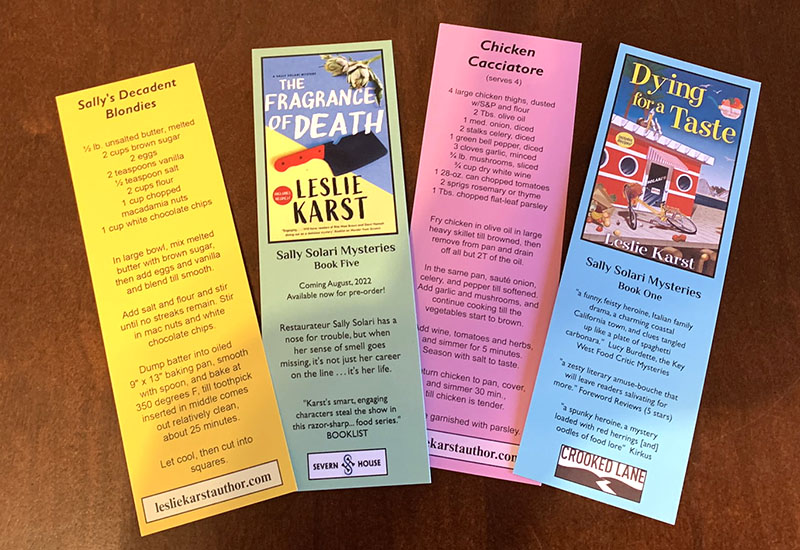

Some bookmarks that did entice people to pick them up were dual-purpose, like these.

Some bookmarks that did entice people to pick them up were dual-purpose, like these.

A tradition at Left Coast Crime is their Author Speed Dating event. How it works: Tables for ten (There were 40 this year) are set up in a large meeting room. Two seats at each table are reserved for authors. The authors rotate from table to table and each has two minutes to talk/pitch/promote themselves and/or their books. They also bring swag to distribute at each table.

A tradition at Left Coast Crime is their Author Speed Dating event. How it works: Tables for ten (There were 40 this year) are set up in a large meeting room. Two seats at each table are reserved for authors. The authors rotate from table to table and each has two minutes to talk/pitch/promote themselves and/or their books. They also bring swag to distribute at each table.

My observations.

The two-minute rule was enforced, which means authors had to be well prepared. Since handing out swag eats up precious seconds, authors were advised to let their partner hand out the swag while they talked. A fair number of them weren’t able to follow this simple direction. Some overran their time, ignoring the bell and finishing their prepared talks, eating up their partner’s time or having to arrive late to the next table.

The presentations varied from rehearsed and memorized speeches to stumbling or rambling attempts to summarize the gist of their stories. The best ones were those who knew their material well enough to make it sound off the cuff. Those attending are going to be listening to eighty two-minute presentations in a room that’s probably not going to have the best acoustics. Being able to be heard was challenge enough for some.

Takeaway: if you’re doing a presentation like this, adhere to the time constraints. Practice your material until it doesn’t sound practiced. If the organizers offer advice, take it.

And now, back to the swag. Handing out swag to a captive audience is better than leaving it on a giant table. But remember the purpose of the swag. To make people want to know more about you and your books.

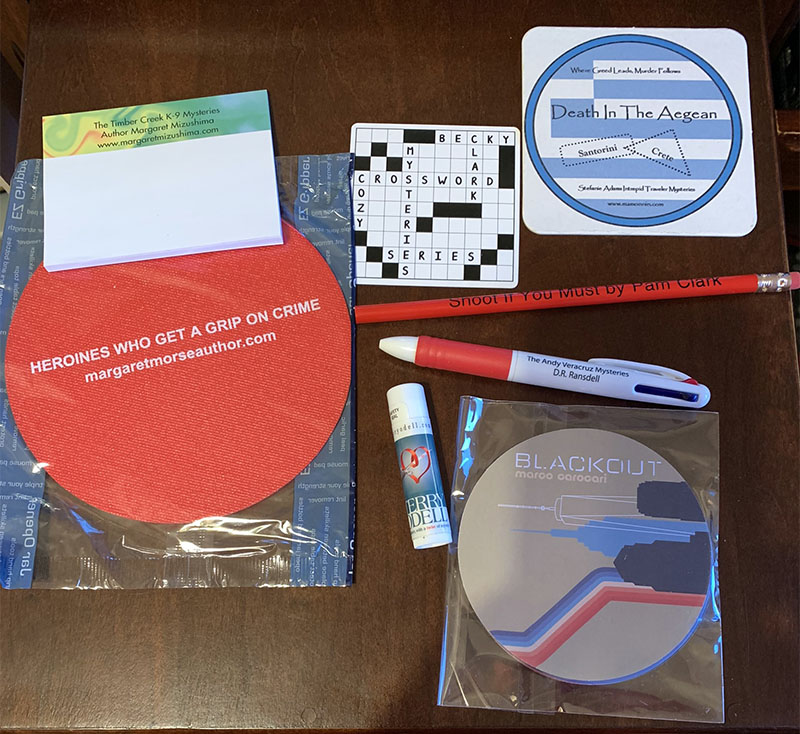

Here are some swag items handed out at the Speed Dating event that, in my opinion, missed the mark.

From left to right. A nice, sturdy magnet. A vial of perfume. A cute magnet. A pin-on button.

From left to right. A nice, sturdy magnet. A vial of perfume. A cute magnet. A pin-on button.

Problems with all of them: What are they about? Would you even know they were from an author? Because by the time you get home with them, you’ll have no recollection of who gave them to you. (Note: some swag was handed out in cute little pouches and may have included something about the author, but once you take the items out of the pouch, all connections are lost.) With the perfume, you’re risking the recipient not liking it. With a pin, would readers wear them? Pin them to something else?

Better ideas are things that readers will have a reason to keep and use. Every time they use them, they (one hopes) will remember the author. One author had Hershey’s Miniatures relabeled with his book cover. Great idea—until you eat the candy. Will they save the label? Maybe. I didn’t, but they worked in that I struck up a conversation with that author and did look him up.

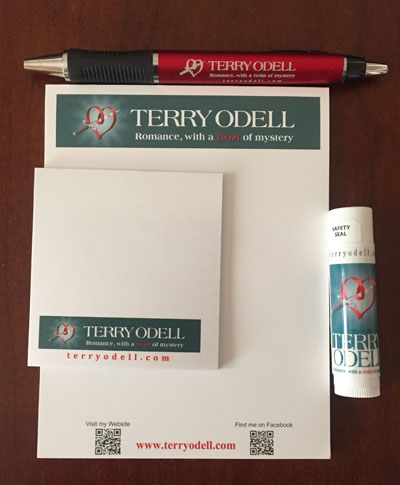

I know my lip balm is what people remember about me. Sticky notes, pens, pencils, coasters, magnets that do mention the author, and even a jar opener/gripper thing make for better swag. More expensive, yes. But if you’re spending money, it ought to be working for you.

I know my lip balm is what people remember about me. Sticky notes, pens, pencils, coasters, magnets that do mention the author, and even a jar opener/gripper thing make for better swag. More expensive, yes. But if you’re spending money, it ought to be working for you.

Your turn. What swag are you likely to pick up? If you hand out swag, what’s been effective?

Available Now. In the Crosshairs, Book 4 in my Triple-D Romantic Suspense series.

Available Now. In the Crosshairs, Book 4 in my Triple-D Romantic Suspense series.

Changing Your Life Won’t Make Things Easier

There’s more to ranch life than minding cattle. After his stint as an army Ranger, Frank Wembly loves the peaceful life as a cowboy.

Financial advisor Kiera O’Leary sets off to pursue her dream of being a photographer until a car-meets-cow incident forces a shift in plans. Instead, she finds herself in the middle of a mystery, one with potentially deadly consequences.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.” Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.” Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

By Debbie Burke

When was the last time you saw a social media post that compelled you to buy a book?

My answer: almost never.

Then I ran across thriller author Avanti Centrae. Her fresh, unique strategy intrigued me. Here’s how we met:

Recently Avanti followed me on Twitter, I followed her back. Next, a direct message arrived from her.

Normally, DMs are off-putting if you don’t already know a person. Sue Coletta covered this in her excellent post Top 10 Social Media Mistakes for Writers.

Avanti’s DM wasn’t like the usual creepy offers I receive. I never anticipated there would be so many widowed, high-ranking military doctors dying to make my acquaintance.

In contrast, Avanti’s message thanked me for following her and included a photo of her book cover for VanOps: The Lost Power with an invitation to read sample chapters on her website. Her logline is “DaVinci Code meets Tomb Raider.”

Next I checked out her website. It was professional and showed she knew a thing or two about marketing.

A bonus freebie (e.g. sample chapters, a short story) is an effective method to build a mailing list. Even though I already subscribe to more newsletters than I can keep up with, I took the bait.

Here’s where the fun began with her sign-up form:

Instead of a bland form asking for name and email, this was an attention-grabber for an espionage thriller series.

She followed up with this confirmation email:

|

I recently re-watched the movie Seabiscuit, a film adaptation of Seabiscuit: An American Legend (1999) by Laura Hillenbrand. I had seen the movie several years before I picked up a keyboard with the intention of writing my own novels, but seeing the story for the second time gave me a chance to analyze it from a writer’s perspective.

* * *

SECOND CHANCES

The movie is set in 1930’s depression-era America, a time when many people lost everything except their longing for a second chance at life. The plot follows four independent characters who had suffered in different ways, but whose paths converge to result in a surprising accomplishment.

AND PARALLEL PLOTS

Charles Howard (Jeff Bridges) was a wealthy and powerful automobile magnate, but the loss of his only child in an automobile accident destroyed his marriage. On a trip to Mexico with several friends, Howard became interested in horse-racing, though he knew little about the sport.

Tom Smith (Chris Cooper) was an over-the-hill trainer known for his unusual methods and devotion to rehabilitating injured animals. He uttered a crucial line in the film, “You know, you don’t throw a whole life away just ’cause he’s banged up a little.” Although Smith was referring to a horse, the quote clearly referred to all the main characters.

Red Pollard (Tobey Maguire) was a young man from an educated family whose parents were ruined by the depression. Bitter and angry, Pollard’s love of horses pushed him into becoming a jockey even though he was considered too big for the sport.

Seabiscuit (10 different horses played the role of Seabiscuit in the film) was a grandson of the great Man o’ War, but hadn’t amounted to much as a race horse. He was considered lazy and untrainable by those who tried to turn him into a winner. Besides, he was small for a thoroughbred. Hardly the stuff of champions

COMING TOGETHER

The four characters lived in parallel universes until Howard considered getting into the horse-racing business. Deciding against the well-known, successful trainers, Howard hired Tom Smith, and Smith, in turn, opted for the unlikely Seabiscuit as the horse to train. Then he went even further afield when he hired Pollard as the jockey. This was a team of misfits, all looking in different ways for a second chance at life. As Howard explains to a crowd in a memorable scene: “The horse is too small, the jockey too big, the trainer too old, and I’m too dumb to know the difference.”

You can see where this is going. Seabiscuit began to win races, and soon the horse was heralded as the best racehorse on the west coast. But the real horse-racing establishment was housed in the eastern United States. And it was there that the magnificent stallion War Admiral reined supreme. (Pun intended.)

In 1937, War Admiral won the Triple Crown, only the fourth horse do so, and was also named “Horse of the Year.” A majestic animal, War Admiral inspired awe in any who witnessed his races. So, of course, Charles Howard wanted to match his upstart steed against the best.

Samuel Riddle, the owner of War Admiral, had no interest in committing his champion to a head-to-head contest with Seabiscuit. He had nothing to gain and everything to lose. But Charles Howard took his message to the masses in 1938, and convinced people who were themselves yearning for a second chance at life to see a match race through the lens of the underdog. Howard’s strategy worked, and Riddle finally agreed to the match race, though on the terms that it had to be run on War Admiral’s home track.

The “Match of the Century” was held on November 1, 1938. According to the Wikipedia entry on Seabiscuit, 40,000 people showed up at Pimlico for the race and another 40 million listened to it on the radio! Since Pollard was still recovering from a broken leg suffered in a training accident, George Woolf, a well-known jockey and friend of Pollard’s, was aboard Seabiscuit for the showdown.

THE RACE

Knowing War Admiral liked to go immediately to the front, Smith’s strategy was for Seabiscuit to jump out to an early lead and set the pace, which he did. Smith also instructed Woolf to let War Admiral catch up in the backstretch, which he also did. Running shoulder-to-shoulder, the two horses rounded the final turn.

In a charming bit of moviedom that I doubt actually happened, George Woolf turned to the jockey astride War Admiral as the horses entered the homestretch and said, “So long, Charlie.” Then Seabiscuit pulled away and won the race by four lengths.

* * *

So TKZers: What do you think of the use of parallel plots? Have you used parallel plots in your novels? Do you ever knock your main characters down and give them a second chance at success? Have you ever used both parallel plots and second chances in the same story?

* * *

Two teams of female sleuths follow parallel plot lines to decipher the clues and discover a killer. But the only thing waiting at the finish line is more danger.

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Stephen J. Cannell

The late Stephen J. Cannell was a hugely successful TV writer and developer. Among his hit shows were The Rockford Files, The A-Team, and 21 Jump Street. Later, Cannell became a bestselling novelist, writing stand-alone thrillers and a series featuring LAPD Detective Shane Scully.

Cannell held the Three-Act structure to be foundational. He wrote:

What is the Three-Act structure? Often, when I ask a writer this question I am told that it is a beginning, middle and an end. This is not the answer. A lunch line has a beginning, middle and an end. The Three-Act structure is critical to good dramatic writing, and each act has specific story moves. Every great movie, book or play that has stood the test of time has a solid Three-Act structure. (Elizabethan Dramas were five act plays, but still had a strictly prescribed structure.) The only place where this is not the case is in a one-act play, where “slice of life” writing is the rule.

Since we are not writing novels about having lunch, what do we need from each Act? It’s not complicated.

Act One = Getting the reader bonded with a Lead. Cannell put it succinctly: “Act One is a preparation act for the viewer or reader. They are asking who is the hero. Do I like this person? Is this guy a heavy? Do I care about the relationships? What is the problem for the hero? Is the problem gripping?”

Act Two = Conflict gets progressively more difficult. Here Cannell suggests that a bit of backstory suddenly revealed can be used to create complications. E.g., the baby the woman thought was her own when she left the hospital in Act One was actually switched by a nurse. He also reminds us that both protagonist and antagonist must be in motion, making moves to try to gain the advantage, not “standing around.” At the end of Act Two, things are looking dark for the Lead.

Act Three = An ending can be upbeat or downbeat, but it needs to clearly resolve the story problem.

As we all know, that long Act Two can frequently become a slog. There are many possible reasons why this happens, which we don’t have time to go into here (I will modestly suggest that Plotman, superhero of the writers’ world, has the answers). Cannell suggests one way to get you going again:

Once we get past the complication and are into Act Two, we sometimes get stuck. “What do I do now?” “Where does this protagonist go from here?” The plotting in Act Two often starts to get linear (a writer’s expression meaning the character is following a string, knocking on doors, just getting information). This is the dullest kind of material. We get frustrated and want to quit.

Here’s a great trick: When you get to this place, go around and become the antagonist. You probably haven’t been paying much attention to him or her. Now you get in the antagonist’s head and you’re looking back at the story to date from that point of view.

“Wait a minute… Rockford went to my nightclub and asked my bartender where I lived. Who is this guy Rockford? Did anybody get his address? His license plate? I’m gonna find out where he lives! Let’s go over to his trailer and search the place.” Under his mattress maybe the heavy finds his gun (in Rockford’s case, it was usually hidden in his Oreo cookie jar). His P.I. license is on the wall. Now the heavy knows he’s being investigated by a P.I. Okay, let’s use his gun to kill our next victim. Rockford gets arrested, charged with murder. End of Act Two.

See how easy it works? The destruction of the hero’s plan. Now he’s going to the gas chamber.

Boom! (Of course in Act Three Rockford gets out of it. This is a series, after all!)

I call Cannell’s trick the “shadow story.” The shadow story is what goes on “off screen” (or “off page” if you will). I like to make shadow story notes to myself throughout he writing (I use Scrivener for this, but you can also use the Comment function in Word). Just pause every now and then and ask what the main characters not in your current scene are doing and planning. What are their motives? Secrets? Desires?

Your shadow story will give you more than enough plot material to get you through that long middle portion of your novel.

Discuss!

by Steve Hooley

I enjoy browsing the archives of the Kill Zone Blog from time to time. There are many posts hiding here that contain a wealth of wisdom and good advice and are worth rereading.

Recently, I was looking for articles on foreshadowing and found buried treasure in a post by Jodie Renner from January, 2014. I had glanced at several discussions of foreshadowing and found that Jodie’s article was concise, well organized, and perfect for our discussion today.

Since it has been eight years, I thought it was worth revisiting and using for today’s discussion. So, nuggets of wisdom from the past (the archives) and a discussion on ways we can set up the narrative for the future

I have summarized the article below, but the original article is well worth rereading.

Keep your reader curious and worried, and keep them turning pages.

“Foreshadowing is about sprinkling in subtle little hints and clues…about possible revelations, complications, and trouble to come.”

No author intrusion giving an aside to the reader

Hopefully Jodie will be able to stop by today, say hello, answer some questions in the comments, and add any additional points or tips she’s acquired since 2014.

By the way, a thorough discussion on foreshadowing is found in Jodie’s book, Writing a Killer Thriller, an Editor’s Guide to Writing Compelling Fiction.

Questions and Discussion

“There are three rules to writing a novel. Unfortunately, no one knows what they are.”

This quote is usually attributed to W. Somerset Maugham, and it’s been kicked around a lot over the years. There may, or may not, be some truth to it depending on your view, your experience, and your sense of humor. But there is something to the rule of three.

The rule of three is a staple in the writing world. It’s known by many names—the triple, the triad, the trebling, and the trilogy. The three-act structure of beginning, middle, and end is a prime example of the rule of three.

The rule of three suggests that a trio of events, characters, or phrases is more effective, satisfying, or humorous than other numbers. Think of the “walks into a bar” jokes. An Englishman, an Irishman, and a Scotsman or a brunette, a redhead, and a blonde.

The rule of three can apply to words, sentences, and paragraphs. It can be used to frame chapters, whole books, and a series of books. The three-rule also applies to poetry, oral storytelling, and films.

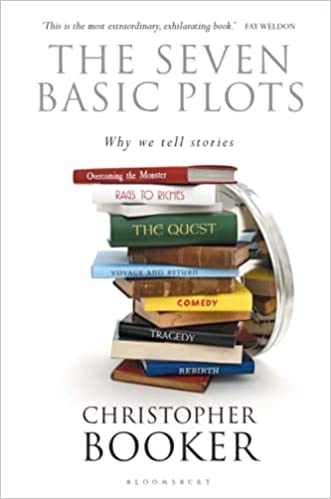

What got me going on the rule of three this morning was stumbling on a writing resource titled The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories. It’s written by Christopher Booker and first published in 2004. Apparently, Booker worked on this book for thirty-four years.

I’m going to quote from Mr. Booker’s book where he deals with the rule of three:

“The third event in a series of events becomes ‘the final trigger for something important to happen.’ This pattern often appears in childhood series like Goldilocks and the Three Bears, Cinderella, and Little Red Riding Hood. It also appears in adult works like Fiddler on the Roof, A Christmas Carol, and Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar.

In stories, the Rule of Three conveys the gradual resolution of a process that leads to transformation. This transformation can be downwards as well as upwards. The Rule of Three is expressed in four ways:

1. The simple or cumulative three. For example, Cinderella’s three visits to the ball.

2. The ascending three where each event is more significant than the preceding. For example, the hero must first win bronze, then silver, then gold.

3. The contrasting three where only the third has positive value. For example, The Three Little Pigs—two of whose houses were blown down by the Big Bad Wolf.

4. The final or dialectical form of three. For example, Goldilocks and her bowls of porridge. The first is wrong in one way, the second is wrong in an opposite way, and the third is just right.”

I also stumbled upon a formula for the rule of three. This is often used in joke telling and comedy writing. It’s called the SAP test.

S = Setup (preparation)

A = Anticipation (triple)

P = Punchline (story payoff)

Let’s look at a joke by comedian Jon Stewart:

“I celebrated Thanksgiving in an old-fashioned way. I invited everyone in my neighborhood to my house, we had an enormous feast, and then I killed them and took their land.”

The rule of three appears so many times in so many ways that it’s barely noticed as a delivery technique. In the rule’s simplest form, outlined in Aristotle’s Poetics, it’s the classic beginning, middle, and end which is a time-proven structure. But think of all the times you’ve encountered the rule of three:

The truth, the whole, truth, and nothing but the truth.

Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Reading, ‘riting, and ‘rithmetic.

Ready, aim, fire.

On your mark. Get set. Go.

Veni. Vidi. Vici.

Solid, liquid, and gas.

Three wishes.

Stop, look, and listen.

Snap. Crackle. Pop.

Blood, sweat, and tears.

Turn on. Tune in. Drop out.

Faster. Higher. Stronger.

See no evil. Hear no evil. Speak no evil.

What about you Kill Zoners? How often have you used the rule of three in your works? And can you add to the examples?

Fiction writers are sleight of hand masters. We create stories about people who do not really exist doing things that never happened in places that may or may not be real, all the while painting word pictures in readers’ heads. Sometimes with our eyes closed.

One question that comes up frequently when interacting with readers is some variation of “How do you do your research?” Depending on the audience, I have a lengthy, nuanced response that deals with building an extensive contacts list of people who not only know stuff, but will return my phone calls. That’s all true, but in reality, I don’t turn to the experts all that often.

For the most part, I cheat. I make stuff up. I can’t count the number of scenes that have played out inside the suburban house I grew up in. My wife grew up in a creepier house than I did, so that one has been featured many times, too. In Total Mayhem, Gail Bonneville and Venice Alexander break into the fictional Northern Neck Academy, which looks very, very much like the swanky private school where I worked during my college summers as a counselor at a day camp for overprivileged rich kids.

By knowing in my head what a place looks like–because I’ve been there and can report from memory to the page–making the settings real for the reader is a matter of reporting what I see in the pictures in my memory banks.

My research for Six Minutes to Freedom took me to the jungles and barrios of Panama, so every time a jungle appears in a book, those are the jungles I see. I have been in the West Wing of the White House exactly one time and even managed a peek at the Oval Office, so I know the feel of the place. (NOTE: Besides the Oval itself, the West Wing looks nothing like the version shown in the television show bearing its name.)

Google Earth is a gift to writers.

My book Final Target features a lengthy escape sequence where Jonathan Grave needs to get his team and a busload of orphans to an exfiltration point on the northern coast of the Yucatan Peninsula while pursued by cartel bad guys. In part because the cartel bad guys are very real and quite active in those parts, I had no desire and zero intention to visit the place.

So, I cheated. Google Earth offers a “street view” function that allowed me to “drive” Jonathan’s route to the exfil point. I don’t dwell on specific structures, but I did mention landmarks at different intersections, and I was able to see where and how the nature of the vegetation changes. I even pinpointed the big house where the final shootout happened.

Everything is research.

Back when I still had my Big Boy Job, my duties took me to Ottawa, where I fell in love with the city. (Actually, I’ve fallen in love with a lot of places in Canada.) In High Treason, bad guys spirit Jonathan’s precious cargo across the border into Canada, and I needed a location for the final conflict. I remembered from my visit that islands in the middle of the Ottawa River, very near the government buildings. Those would suit my purposes perfectly. But those islands don’t have the kind of structures I needed.

So, I cheated. I remembered from an earlier vacation trip to Ireland that we visited Kilmainham Gaol in Dublin, and that would be perfect. I changed its name and planted it on that island in the Ottawa River. Then I blew a lot of it up. I did get a few letters from readers who felt it necessary to tell me that there is, in fact, no prison on those islands, but not as many as I had feared.

It’s okay not to be real.

Writers are inherently inquisitive people, I think, and our passion to do research too often takes us down rabbit holes where countless hours are wasted. I work to deadlines, so I often don’t have that luxury. I have to remind myself that fiction is merely the impression of reality. I don’t have to be able to do all of the things that my characters can do. All I have to do is convince the reader that the characters are able to do the stuff they do.

It’s all a part of going on the great pretend.

How about you, TKZ family? Any research shortcuts you want to share?