“There are three rules to writing a novel. Unfortunately, no one knows what they are.”

This quote is usually attributed to W. Somerset Maugham, and it’s been kicked around a lot over the years. There may, or may not, be some truth to it depending on your view, your experience, and your sense of humor. But there is something to the rule of three.

The rule of three is a staple in the writing world. It’s known by many names—the triple, the triad, the trebling, and the trilogy. The three-act structure of beginning, middle, and end is a prime example of the rule of three.

The rule of three suggests that a trio of events, characters, or phrases is more effective, satisfying, or humorous than other numbers. Think of the “walks into a bar” jokes. An Englishman, an Irishman, and a Scotsman or a brunette, a redhead, and a blonde.

The rule of three can apply to words, sentences, and paragraphs. It can be used to frame chapters, whole books, and a series of books. The three-rule also applies to poetry, oral storytelling, and films.

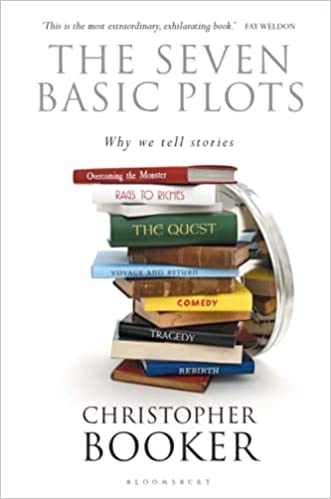

What got me going on the rule of three this morning was stumbling on a writing resource titled The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories. It’s written by Christopher Booker and first published in 2004. Apparently, Booker worked on this book for thirty-four years.

I’m going to quote from Mr. Booker’s book where he deals with the rule of three:

“The third event in a series of events becomes ‘the final trigger for something important to happen.’ This pattern often appears in childhood series like Goldilocks and the Three Bears, Cinderella, and Little Red Riding Hood. It also appears in adult works like Fiddler on the Roof, A Christmas Carol, and Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar.

In stories, the Rule of Three conveys the gradual resolution of a process that leads to transformation. This transformation can be downwards as well as upwards. The Rule of Three is expressed in four ways:

1. The simple or cumulative three. For example, Cinderella’s three visits to the ball.

2. The ascending three where each event is more significant than the preceding. For example, the hero must first win bronze, then silver, then gold.

3. The contrasting three where only the third has positive value. For example, The Three Little Pigs—two of whose houses were blown down by the Big Bad Wolf.

4. The final or dialectical form of three. For example, Goldilocks and her bowls of porridge. The first is wrong in one way, the second is wrong in an opposite way, and the third is just right.”

I also stumbled upon a formula for the rule of three. This is often used in joke telling and comedy writing. It’s called the SAP test.

S = Setup (preparation)

A = Anticipation (triple)

P = Punchline (story payoff)

Let’s look at a joke by comedian Jon Stewart:

“I celebrated Thanksgiving in an old-fashioned way. I invited everyone in my neighborhood to my house, we had an enormous feast, and then I killed them and took their land.”

The rule of three appears so many times in so many ways that it’s barely noticed as a delivery technique. In the rule’s simplest form, outlined in Aristotle’s Poetics, it’s the classic beginning, middle, and end which is a time-proven structure. But think of all the times you’ve encountered the rule of three:

The truth, the whole, truth, and nothing but the truth.

Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Reading, ‘riting, and ‘rithmetic.

Ready, aim, fire.

On your mark. Get set. Go.

Veni. Vidi. Vici.

Solid, liquid, and gas.

Three wishes.

Stop, look, and listen.

Snap. Crackle. Pop.

Blood, sweat, and tears.

Turn on. Tune in. Drop out.

Faster. Higher. Stronger.

See no evil. Hear no evil. Speak no evil.

What about you Kill Zoners? How often have you used the rule of three in your works? And can you add to the examples?

A priest, a rabbi, and a nun walk into a bar. And the bartender says, “What is this, some kind of joke?”

Yes, three is natural. The triangle is the strongest structural form (e.g., the geodesic dome). Our lives are built on threes: we wake up in the morning (Act 1); meet the challenges of the day (Act 2); wind down and go to bed (Act 3). We have a childhood, a (hopefully) long adulthood, and then the Autumn of our years.

A story? Get your Lead up a tree; throw rocks at him; get him down.

As a lawyer, Jim, you’ll recognize the three act structure in a trial – the opening, the evidence, and the closing. Rocks? How about a flamethrower?

A long time ago when I first started to “learn to write”, I heard the Rule of 3 as:

1. Sets the norm

2. Sets the pattern

3. Breaks the pattern

I’ve used this a lot since then.

Good analogy, Joe. I’ve also heard it put “the situation, the struggle, and the solution”.

We’re wired to threes in the actual prose, not just the structure. There’s a rhythm in threes.

Things presented in threes just seem to stick with us: Faith, Hope. and Charity. Winken, Blinken, and Nod. Blood, Sweat and Tears. Stop, Look and Listen. Stop, Drop and Roll. The US Marines found that grouping things in threes helped people remember training, which in turn, helped keep them alive. They experimented with a rule of four, and retention and effectiveness plummeted.

I have to go back through my sentences to make sure I’m not overusing three examples.

Interesting point about the Marines organizing their training in threes, Terry. “In the air, on land, and sea”.

The whole Corps is based on threes: three men in a fire team, three fire teams in a squad, three squads in a platoon, etc right on up the structure to three Marine Divisions and three Marine Airwings.

But as it pertains to Writing, I learned once a long time ago that if you give a reader four like items to remember in a sentence (for example, four predicate adjectives), the reader will most often remember 1, 2, and 4. He will most often forget the third item. So it’s better to limit items to three.

However, knowledge is power. This can also be a good way to leave a clue in a mystery and be relatively sure the reader will miss it.

Interesting breakdown on the Marines, Harvey. Also, an interesting point about using four and the reader skipping over three – and using it as a clue device. Thanks for sharing this!

Yeah, I took it as how-to advice, too.

Great post, Garry. I’m with you on the power of the rule of three in fiction. I’m with Jim on the three act structure. For instance, you can break down a mystery novel into three parts that basically match the three acts: 1-Problem/Puzzle, 2-Investigation, 3-Solution. Of course, there’s more to it than that, but it’s good starting point.

These days I often break the second act into two acts of its own, on either side of Jim’s “Mirror Moment.” His golden triangle of What came before the start of the actual plot (pre-story), the mid-point, and the transformation at the climax is another rule of three.

During a novel, there are three outcomes to a scene that move the story forward and make things worse for our hero when they’re trying to achieve their goal in any particular scene: No, they didn’t get what they want. No, and furthermore, this now happens. Yes, they got what they wanted, BUT, now have to deal with THIS new thing.

Thanks for an insightful rundown on the rule of three this Thursday morning. Keep on having great days!

I’m with you, Dale, on breaking down Act II into two parts, before and after the mirror moment.

That makes a lot of sense to break Act II into two parts, Steve. There’s a “rule” of two plot points in the second act that I’m aware of. Sue is much more up on where the plot (pinch?) points should be in the acts than I am. Sue?

I mentioned to Joe (above) about the three act structure being expressed as situation, struggle, and solution. Your “problem/puzzle, investigation, and solution” says this equally well, Dale. I’ve been involves in screenplay structure study recently, and I’ve picked up on a formula commonly used that says the ideal length of the three acts is 1/6 problem/puzzle, 2/3 investigation, and 1/6 solution.

I’ve heard the three act breakdown as 2 reels, 4 reels, and 2 reels, using 15 minute reels.

Interesting comparison. Thanks JGA.

Real estate: location, location, location

There’s another real estate saying, Brenda. “It’s always the right time to buy, and it’s always the right time to sell.”

Right now in real estate, it’s a great time to sell, but a miserable time to buy because the market is so hot. My BIL wanted me to sell my huge home and land to get top dollar, but I asked him where the heck could I find to live.

Great analysis, Garry.

Three strikes and you’re out.

Thanks, Debbie. There’s a rule of three coming from WWI trench warfare. No third man on a match while lighting cigarettes. See ’em. Sight ’em. Shoot ’em.

In A Writers Guide to Active Setting, Mary Buckham states: “There’s power in the use of three beats in writing. A sound and two smells. A texture and two sounds. Don’t overuse it, but when you want to make a quick, clear anchor for the reader, the three-beat style can be powerful.”

It’s in our DNA–literally. DNA is a string of molecules we call bases. They are called Adenine, Cytosine, Guanine, and Thymine–or A, C, G, T for short. Triplets of these bases “code” for various Amino Acids. For example, ACC codes for tryptophan and TTT or TTC codes for lysine. We call strings of amino acids proteins and these help build our bodies. Proteins that catalyze actions in the body we call enzymes. All of life is simply a series of chemical reactions catalyzed by these enzymes. So, the base triplets in our DNA dictate everything.

Nice to hear from you, Doug. Great equation. Thanks!

Interesting topic! I can think of two triples:

Father, Son, and Holy Ghost

“Tell me and I forget. Teach me and I remember. Involve me and I learn.” -Ben Franklin

I thought of the same references. Excellent choices.

Mr. Franklin was bang-on about training people, Priscilla. Explain. Show. Do.

Great post, Garry! Nailed it again…

Having been a musician for the bulk of my life, I had to *chime* in here. 🙂

It’s been said that the most pleasing harmony to most human ears is three part, notes exactly one-third apart on the scale. This is true particularly with vocal music, barbershop quartets notwithstanding. They’re a whole different animal.

There’s something about three part harmony that’s soothing. Maybe because it winds into our three part DNA and takes up residence there. Maybe because there’s a completeness for which humans long. Take one of the notes away, and it’s just not the same.

Have a great day, Garry! Anticipating your next blog post on dyingwords.net…

Thank you, Deb. Good Thursday morning, BTW. I’m no musician by any means. I can barely play the radio. Your comment got me thinking about another musical trio – Three Dog Night and Just An Old-Fashioned Love Song “coming down in three-part harmony”.

A friend in graduate school talked about the Devil’s Trinity in music, a term he may have made up. This type of musical moment is essentially heart arrhythmia, and humans find it instinctively wrong even when they don’t connect it to heart rhythm. It’s considered demonic and is used in music to creep out the listener.

Great post. I follow the three act structure, but didn’t equate it to all the ways it shows up outside of story structure. Excellent. Thank you.

Most welcome, Cecilia. I think there are almost endless examples of the rule of three. Our education system – elementary, high, and college. Government – legislative, executive, and judiciary. Defense – army, navy, and air. Food – breakfast, lunch, and dinner (supper). Starbucks – demi, grande, and venti.

Great post, Garry.

We live in three-dimensional space. But then there’s that fourth dimension of time. I wonder how that fits in.

Thanks, Kay. Einstein blended the third part of “reality” into space-time. So far, every study and experiment proves him right.

There’s also that dimension in which dark matter has extent. We can’t see it, but its mass makes itself felt.

If you do a search for the Rule of Three, you’ll get a lot of results that look nothing like this. Mine is a rule of thumb for determining if a scene should stay or leave during rewrites as well as writing the scene in the first place.

If a scene doesn’t contain at least one or two plot points (information or events which move the plot forward), and one or two character points (important character information) so that you have at least three points total, then it should be tossed, and whatever points included in that scene should be added to another scene.

And then there’s the character trinity. Three characters who work with and against each other, and they are volatile enough for the dynamic to keep shifting.

In classic STAR TREK, Kirk, Spock, and McCoy were an ideal heart, mind, and action trinity. When a problem needed to be solved, Spock was the logical mind, McCoy the emotional heart, and Kirk took both and created the ideal action.

These characters can also be considered a thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. Two opposite sides of a problem from Spock and McCoy, and Kirk pulling both together to find the solution.

Another good example of the character trinity is Harry, Hermione, and Ron in the Harry Potter series.

Excellent example in Star Trek, Marilynn. Harry Potter, too.

I’m with you, Garry. All my scenes are thusly structured: Opening, Obstacle, Outcome.

Oh, and here’s one slightly off-topic, but I’ll give it anyway:

In photography, there’s the famous Rule of Thirds.

I was going to mention the photography rule of thirds, Harald. I came across it while researching this piece and it stuck me as being completely valid. “Opening, Obstacle, Outcome.” Thanks!

In my thriller, therapy takes place in three different locations. There were only three people in Hitler’s Mercedes as he left for Nuremberg on the day Geli Raubal was shot, the clue that solved the mystery of how she was killed in a locked-room at the same time that Hitler addressed several dozen fans from his window at Hotel Deutscher Hof.

Oooo, I want to read this! Make a note. I’ll buy it.

Great post, Garry. Sorry I’m late. I finished my thriller and synopsis Wednesday, and took a little me-time yesterday. Nature is filled with threes. And I’ll let you in a little secret. One of the reasons we looked at our house is because it’s #21 2+1=3. I’ve always been attracted to threes. 🙂

Congrats on completion, Sue, How many is this now? And good on you to do some me-time – out in nature, I’d guess.