by Jodie Renner, editor & author

by Jodie Renner, editor & author

Most of today’s popular fiction is written in first-person POV (I) or third-person limited point of view (he, she), both of which show us the story mainly from inside the character’s head and body. These narrative techniques engage readers much more emotionally than the more distant third-person omniscient, which was popular in previous centuries.

Current popular fiction, although a long way from the old omniscient style, still employs a variety of narrative distances, depending on the genre, the target readership, and the writer’s own comfort level. There is a whole spectrum when it comes to narrative distance, from plot-driven military or action-adventure novels and historical sagas at one end to character-driven romantic suspense and romance at the other.

Today’s post focuses on close or intimate narrative distance – how to engage readers emotionally, bond them with your character, and draw them deep into your story, so they can’t put it down. And how to avoid interrupting as the author, which some readers might even find akin to “mansplaining.” See a great post here on TKZ by bestselling thriller writer, Robert Dugoni, “Hey, Butt Out! I’m Reading Here!”

Most female readers (and apparently females make up about 70% of readers of novels) prefer to identify closely with the main character. The reading experience is more satisfying when we connect emotionally with the protagonist, worrying about them and rooting for them.

What is third-person limited POV? As Dan Brown says, “limited or ‘close’ third point of view (a narrative that adheres to a single character) … gives you the ability to be inside a character’s thoughts, feelings, and sensations, which can give readers a deeper experience of character and scene, and is the most common way to use point of view.”

(For an introduction to point of view in fiction, especially deep point of view or close third-person POV, see my articles here on TKZ: POV 101, POV 102, and POV 103)

From third-person limited, you can decide to go even deeper, into close third person or deep point of view to create an immersive experience where readers are more emotionally invested, feeling like participants rather than observers.

As David Mamet says, “Deep point of view is a way of writing fiction in third-person limited that silences the narrative voice and takes the reader directly into a character’s mind…. Deep POV creates a deeper connection between readers and characters.”

In deep POV, the author writes as the character instead of about him. The character and his world come to life for us as we vicariously share his experiences and feel his struggles, pain, triumphs, and disappointments.

As editor and author Beth Hill says, “deep POV…is a way of pairing third-person POV with a close narrative distance. It’s a way of creating the intimacy of first-person narration with a third-person point of view.” (And without all those I – I – I’s.)

Depending on your personal style, you could decide to write in a deeper, more subjective third-person point of view for a whole novel or story or reserve this closer technique for more critical or intimate scenes.

Assuming you write in third person and want to engage your readers more and immerse them in your story world, here are some tips for getting deeper into the psyche of your character, starting with more general tips and working down to fine-tuning.

~ First, decide whose scene it is.

Most of the scenes will be from the viewpoint of your protagonist. We know what your lead character is thinking and feeling, as we’re in their head and body. But we only know the feelings and reactions of the others by what the POV character perceives – by their words, actions, body language, facial expressions, tone of voice, etc.

But sometimes you’ll want to write a scene from the point of view of another character. If you choose to use multiple POVs, make sure you only go into the head of important characters such as the love interest, someone close to the MC, or the antagonist. But as readers, we are (or should be) bonded to your MC, so it’s best to show more scenes from the viewpoint of your protagonist than all the others combined – about 70% is optional to keep readers satisfied.

How do you decide whose POV a scene will be told through? Ask yourself these questions: Who has the most at stake in that scene, the most to lose? Which character is invested the most in what’s going on? Who will be most affected by the events of the scene and change the most by the end of the scene?

~ When starting a new scene or chapter, start with the name of the POV character.

The first name a reader sees is the person they assume is the viewpoint character, the one they’re following for that scene. And don’t open a scene or chapter with “he” or “she” – that’s too vague and confusing. Readers want to know right away whose head we’re in, so name the viewpoint character right in the very first sentence.

~ Avoid head-hopping. Get into that character’s head and body and stay there for the whole scene (or most of it).

Don’t suddenly jump into the thoughts or internal reactions of others, and try to avoid stepping back into authorial (omniscient) POV, where you’re surveying the whole scene from afar.

Stick to the general guideline of one POV per scene. Viewpoint shifts within a scene can be jolting, disorienting, and annoying if not done consciously and with care. (On the other hand, when expertly executed, they can work. Nora Roberts has definitely mastered this difficult technique.)

Become that person for the scene. Are they anxious? Cold? Tired? Uncomfortable? Annoyed? Scared? Elated? We should be able to only see, hear, smell, taste, touch and feel what they do. Don’t include any details they wouldn’t be aware of.

~ Refer to the POV character in the most informal way, as he would think of himself.

Use the POV character’s name at the beginning of scenes, then only when needed for clarity. If we’re in Daniel’s head, he’s not thinking of himself as “Dr. Daniel Norton.” He’s thinking of himself as Daniel or Dan or Danny. When you introduce a new POV character for the first time, you can use their full name and title for clarity if you wish (or just slip it in later), but then switch immediately to what they would call themselves or what most people in their everyday world call them. Most of the time, just “he” or “she” is even better. How often do we think of ourselves using our names? Not often.

~ Don’t describe the POV character’s facial expressions or body language as an outside observer would see them.

Unless she’s looking in a mirror, your character can’t see what her face looks like at any given moment, so avoid phrases like “She blushed beet red.” Instead, say something like, “Her cheeks burned” or “She felt her face flush.” Instead of “Her face went white,” say “She felt the blood drain from her face.”

Or if we’re in a guy’s point of view and he’s angry, don’t say “His brow furrowed and he scowled.” Instead, show his anger from the inside (irate thoughts, clenched teeth), or show him gripping something or aware that his hands have tightened into fists, or whatever.

~ Don’t describe other characters in a way that the POV character wouldn’t. For example, don’t give a detailed description from head to toe of a character the POV character is looking at and already knows very well, like a family member.

~ Refer to other characters by the name the POV character uses for them.

If we’re in Susan’s point of view and her mother walks in, don’t say “The door opened, and Mrs. Wilson walked in, wearing a frayed blue coat.” Say something like, “The door opened, and Mom hurried in, pulling off her old coat.”

~ Show their inner thoughts and reactions often.

To bring the character to life, we need to see how she’s reacting to what’s going on, how she’s feeling about the people around her. Use a mix of indirect and direct thoughts. Short, direct, emphatic thought-reactions, often in italics, help reveal the character’s true feelings and increase intimacy with the readers. For example, What? Or No way. Or What a jerk! Instead of: “They’d been set up” (narration), use: We were set up. (The character’s actual thoughts.) For more on this, see “Using Thought-Reactions to Add Attitude & Immediacy.”

Indirect thought: He wondered where she was.

Direct thought: Where is she? Or: Where the hell is she, anyway?

~ Frequently show the POV character’s sensory reactions to their environment, other characters, and what’s happening.

Use as many of the five senses as is appropriate to get us into the skin of the character. Also show fatigue, fear, nervousness, hunger, thirst, heat, cold, etc. That way, readers are drawn in and feel they “are” the character. They worry about the character and are fully engaged.

~ Describe locations and other characters as the POV character perceives them.

Filter descriptions of the setting or other people through the attitudes, opinions, preferences, and sensory reactions of the viewpoint character, using their unique voice and speaking style. Don’t step back and describe the environment, another character, or a room in factual, neutral language. And don’t describe details that character wouldn’t notice or care about.

~ Use only words and phrases that character would use.

If your character is an old prospector, don’t use sophisticated language when describing what he’s perceiving around him or what he’s deciding to do next. Use his natural wording in both his dialogue and his thoughts – and all the narration, too, as those are his observations.

~ Don’t suddenly have a character knowing something just because the readers know it.

If you’re using third-person multiple POV, it’s very effective to sometimes go into the head of another character, maybe the love interest or the villain, in their own scene, without the protagonist present. We readers know this other character by name, but the viewpoint character may not even know they exist. Later, we’re in a scene in the POV of the main character when the secondary character appears to them for the first time. It’s easy to slip up and use that character’s name (or other details about him), since we know it so well, before the protagonist knows it. Watch out for this subtle mistake creeping into your story.

~ Don’t show things the character can’t perceive.

Don’t show something going on behind the character’s back or in another room or location. Similarly, don’t show what’s happening around them when they’re sleeping or unconscious. Instead, show what they’re perceiving as they wake up, or you could leave a line space and start a new scene in the POV of someone else. Avoid slipping into all-seeing, all-knowing, omniscient point of view.

~ Keep the narration in the POV character’s voice.

In deep point of view, not only should the dialogue be in the character’s voice and style, but the narration should too, as that’s really the character’s thoughts and observations. For more on this, see my post, “Tips for Creating an Authentic, Engaging Voice.”

~ Don’t butt in as the author to explain things to the readers, outside of the character’s viewpoint.

Avoid lengthy “info dumps.” Instead, reveal any necessary info in brief form though the character’s POV or as a lively question-and-answer dialogue, with some attitude and tension to spice things up.

Avoid author asides, like “Little did he realize that…” or “If only she had known…”. If the character can’t perceive it at that moment, don’t write it. You can always show danger the protagonist isn’t aware of when you’re in the POV of the villain or other character.

~ Use more action beats instead of dialogue tags.

Instead of: “Why do you think that?” she asked, crossing her arms.

Use: “Why do you think that? She crossed her arms.

We know it’s her talking because we immediately see her doing something.

~ For deeper point of view, try to avoid phrases like “she heard,” “he saw,” “she noticed,” etc.

Since we’re in the character’s head, we know she’s the one who’s hearing and seeing what is being described. Just go directly to what she’s perceiving.

He saw the man staring at his wounds. => The man stared at his wounds.

~ Similarly, use “he wondered,” “she thought,” “he believed,” and “she felt” sparingly. Without those filter words, we’re even closer in to the character’s psyche. Go straight to their thoughts, beliefs, and feelings.

For example, here’s a progression to a closer, deeper point of view:

She thought he was an idiot. –> He seemed like a bit of an idiot. –> What an idiot!

The last is a direct, internal thought or thought-reaction, often expressed in italics if it’s brief and emphatic.

Third-person limited POV:

As she hurried along the dark, deserted street, she heard footsteps approaching behind her, getting closer. She wondered if they’d finally found her.

Deep POV:

She hurried along the dark, deserted street. Footsteps approached behind her, getting closer. Could that be them?

“she heard” and “She wondered” are not necessary and create a bit of a psychic distance.

Do a search for all those describing words, like saw, heard, felt, knew, wondered, noticed, and thought, and explore ways to express the sounds, sights, thoughts, and feelings more directly.

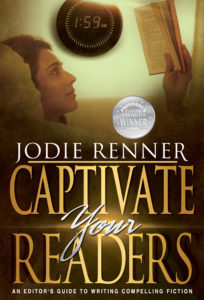

My third writing guide, Captivate Your Readers, is full of practical tips, with examples, for deepening the point of view in your fiction and drawing readers in more emotionally.

My third writing guide, Captivate Your Readers, is full of practical tips, with examples, for deepening the point of view in your fiction and drawing readers in more emotionally.

Readers and writers: Do you have any more tips for deepening point of view in fiction? Or maybe some good before-and-after examples? Please leave them in the comments below. (If you prefer a more distant POV, let’s leave that discussion for another time.) Thanks.

Jodie Renner is a freelance fiction editor and the award-winning author of three writing guides in her series An Editor’s Guide to Writing Compelling Fiction: FIRE UP YOUR FICTION, CAPTIVATE YOUR READERS, and WRITING A KILLER THRILLER, as well as two clickable time-saving e-resources, QUICK CLICKS: Spelling List and QUICK CLICKS: Word Usage. She has also organized and edited two anthologies. Website: https://www.jodierenner.com/, Blog, Resources for Writers, Facebook, Amazon Author Page.

by Jodie Renner,

by Jodie Renner,

My third writing guide,

My third writing guide,

![Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000039_00007]](https://killzoneblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/CHILDHOOD_3_full-202x300.jpg)