by Jodie Renner, editor & author @JodieRennerEd

Book Contests in 2015 for Independent Authors and Publishers

Have you considered entering your book into a contest? You’re not alone. My list here on The Kill Zone last January of 2014 book contests for independent authors and small publishers has received about 4,500 page views since then, so I know there’s a lot of interest in this topic.

Here’s the list, updated for 2015. If you know of any more good book contests for self-published authors, please let me know in the comments below, with the website, so I can add them.

Also, here’s a great list of free writing contests, mainly for short stories and poetry:

27 Free Writing Contests: Legitimate Competitions with Cash Prizes

If you’re experienced at publishing your own books, skip the next six paragraphs and jump down to the contests. If you’ve just recently decided to go the indie route and publish your next book yourself, read the next few paragraphs to ensure your book is ready for entering in book contests.

As you know, the competition is tough for independently published books, and an amateurishly produced book can sink a new author’s reputation before they’ve gotten started, so be sure to put out a professional product (and it is a product). How do you make your book rise up the ranks, sell well, and garner great reviews?

First, be sure to search out professionals to edit and proofread the manuscript, design the cover design, and format it properly. For an excellent, extensive list of professional resources for book design, editing, formatting, and more, check out Elizabeth Craig’s EBook Services Professionals Directory. Also, peruse our list here at TKZ (in the sidebar).

Limited resources for all of those necessities? You can save a lot of money on editing costs by doing a thorough revision and edit yourself first. (If your manuscript is long and rambling, see my recent post on Janice Hardy’s blog, Fiction University: “How to Slash Your Word Count by 20-40% – and tighten your story without losing any of the good stuff!” .) For expert help with the revision process, I recommend James Scott Bell’s excellent guide, Revision & Self-Editing for Publication. Also, check out my award-winning editor’s guides, Fire up Your Fiction and Captivate Your Readers.

You can also cut costs for formatting by doing the basic formatting yourself, per these instructions for formatting your manuscript.

And you can get a high-quality cover design for as low as $99 on sites like this one audcasinos where my three covers were designed – or even lower if you choose a pre-made cover.

Then, once your story is revised, polished, and presented in an attractive, professional-looking package, and you’ve published it, think about entering it in a book contest. Winning an award for your self-published fiction or nonfiction book is a great way to gain recognition and respect, so it rises above the masses. If you win an award, the publicity will boost your book sales, and you can add the award decal to your cover and mention the achievement on your back cover, in the book description, on your website or blog, and in all your marketing and promoting, for that extra edge.

Here’s a list of book awards specifically for independently published books. It’s for your quick info only, and is in no way an endorsement of any of them. Click on the title of the award to go to their website for more details. And do let me know of any good ones I’ve missed. [And if you’re looking to hone your skills and network, you might also be interested in checking out this extensive list (over 120) of Writers’ Conferences & Book Festivals in North America in 2015.]

BOOK CONTESTS FOR INDIE AUTHORS (Click on the titles to go to their sites.)

~ WRITER’S DIGEST SELF-PUBLISHED BOOK AWARDS

Sponsored by: Writer’s Digest Magazine (F&W Media) and Book Marketing Works, LLC

Requirements: Open to all English-language self-published books. Entrants must send a printed and bound book. Evaluated on content, writing quality and overall quality of production and appearance. All books published or revised and reprinted between 2010 and 2015 are eligible.

Early-Bird Deadline: April 1, 2015

What’s in it for you?

- A chance to win $8,000 in cash

- National exposure for your work

- The attention of prospective editors and publishers

- A paid trip to the ever-popular Writer’s Digest Conference!

Fees: Early-bird entry fees (by April 1): $99 for the first entry, and $75 for each additional entry.

Categories: 9, including 1 for poetry and 2 for nonfiction.

Winners notified: by Oct. 12, 2015

Notes: Very popular so very competitive. Your book needs to be professionally produced and sparkle in every way, including a stellar cover an enticing and error-free back cover, clean formatting, and a story that’s been professionally edited and proofread. I have served as judge on this contest three times, so can provide more general info if anyone is interested.

Judges provide feedback/commentary on all books submitted? Yes – minimum 200 words, plus a 1-5 rating on 5 points.

~ WRITER’S DIGEST SELF-PUBLISHED E-BOOK AWARDS

Hasn’t opened yet for 2015. Info from 2014:

This competition spotlights today’s self-published works and honors self-published authors. Whether you’re a professional writer, a part-time freelancer or a self-starting student, here’s your chance to enter WD’s newest competition, exclusively for self-published e-books.

8 different categories

One Grand Prize Winner receives $3,000 cash and lots more.The First-Place Winner in each category receives: $1000 in prize money and more. Honorable Mention Winners will receive $50 worth of Writer’s Digest Books and be promoted on www.writersdigest.com.

Entry fee: Early-bird – $99 for the first entry, $75 for each additional

Deadline: The 2014 deadline was Aug. 1, 2014, so look for this contest in the summer.

A definite plus is that, like the above WD contest, they do send you the judge’s rating and commentary, whether you win or not, which is very helpful.

~ FOREWORD REVIEWS BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARDS

Sponsored by: Foreword Reviews

Open to: all books from independent publishers, including small presses, university presses, and self-published authors, published in 2013.

Deadline: January 15, 2015 (oops! This one has passed. Bookmark this contest for next year, and get your entry in by Dec. or early Jan.)

Winners announced: at American Library Assoc. conference 2015, San Francisco

Entry fee: $99. Send two books per category.

Categories: 62 categories

Judges provide feedback/commentary on all books submitted? No.

Benefits/Prizes: Valuable publicity and $1500 cash prize for the Editor’s Choice in Fiction and Nonfiction.

Details/Advantages: Lots of categories, and “The judging is unique in that after the initial entries have been narrowed down to a group of finalists in each category by the magazine’s team of editors, the finalists are shipped to a hand-selected group of booksellers and librarians who determine the winners. This panel of industry experts use the same criteria for judging as they would use in their own acquisitions process.”

~ INDIEREADER DISCOVERY AWARDS

Sponsored by: Kirkus Indie

Requirements: Open to all self-published books with a valid ISBN. No restrictions on publication dates. Both eBooks and paper books can be submitted.

Deadline: March 2, 2015

Categories: Two main categories (fiction and non-fiction) and 49 sub-categories.

Entry fee: $150 per title, $50 fee for each additional category entered. Submit two copies the first category entered and one each additional category. One paper book and one ebook is preferred, if possible.

Winners announced: at the 2015 Book Expo America (BEA) in New York City.

Judges provide feedback/commentary on all books submitted? No free review anymore. If you want a review, you have to pay for it.

Prizes: Award ceremony at Book Expo America, sticker, professional IndieReader review, exposure. First place gets a review from Kirkus Reviews.

*Note that compared to the others, the above contest has a high entry fee, no cash prizes and no feedback unless you pay for it.

~ NEXT GENERATION INDIE BOOK AWARDS

Sponsored by Independent Book Publishing Professionals Group

Requirements: Open to independent authors and publishers worldwide. Enter books released in 2013 or 2014 or with a 2013 or 2014 copyright date

Categories: 70+ categories to choose from

Deadline: February 13, 2015

Fees: $75 per title for the first category entered, $50 for each additional category. Submission Details: Two copies of the book must be sent for the first category entered plus one copy for each additional category.

Prizes, Benefits, awards: Cash prizes ($1,500 to $100), trophies, awards, listing in catalogue, exposure of top 70 books to NYC literary agent, awards reception, NYC

Details: The largest not-for-profit awards program for independent publishers

Winners notified by: May 15

Judges provide feedback/commentary on all books submitted? No.

~ NATIONAL INDIE EXCELLENCE BOOK AWARDS

Requirements/Eligibility: Open to books with an ISBN, published 2012-2015. Send one copy of the book per category entered.

Deadline: March 31, 2015

Fees: $69 per category

Categories: Lots of Categories!

Winners & Finalists: Will be publicized during Book Expo America; be listed on the official website of the IndieExcellence.com site; etc.

Winners announced: May 15, 2015

~ IPPY AWARDS – INDEPENDENT PUBLISHER BOOK AWARDS

Sponsored by: Jenkins Group Publishing Services, affiliated with Publisher’s Weekly.

Eligibility: independently published titles released between July 1, 2012 and March 15, 2014. Open to authors and publishers worldwide who produce books written in English and intended for the North American market.

Deadline: March 10, 2015

Fees: $85-$95 per category; $55 to also enter the E-Book Awards or Regional Book Awards

Categories: 76 subject categories in National awards; Regional awards for the United States, Canada, and Australia and New Zealand; E-Book Awards with fiction, non-fiction, children’s and regional categories.

Benefits: Winners receive celebration party in NY City, medals, stickers, certificates, national publicity in major trade publications including Publisher’s Weekly and Shelf Awareness. Learn more

~ THE BEN FRANKLIN AWARDS

Sponsored by: IBPA – Independent Book Publishers Association

Info: The IBPA Benjamin Franklin Award for excellence in book publishing is regarded as one of the highest national honors for small and independent publishers.

Deadlines: First Call – Sept. 30, 2015; Second call – Dec. 15, 2015

Categories: 41 book categories + design = 55 categories

Entry fees: IBPA member – $95 per title, per category; Non-IBPA member – $225 for first title, which includes one year’s membership in IBPA; $95 for subsequent entries.

Benefits: Winners recognized at a gala event. Gold winners receive an engraved crystal trophy. Gold and Silver winners receive award certificates along with gold or silver stickers. All winners announced to the major trade journals and media.

Judges provide feedback/commentary on all books submitted? Yes. The Benjamin Franklin Awards are unique in that the entrants receive direct feedback on their titles. The actual judging forms are returned to all participating publishers.

~ READERS’ FAVORITE BOOK AWARDS

Requirements: Accept manuscripts, published and unpublished books, ebooks, audio books, comic books, poetry books and short stories in 100+ genres. No publication date requirement or word count restriction. Entries are accepted worldwide as long as the work is in English.

Fee: $89 per book

Deadline: April1, 2015

Awards: Four award levels plus a finalist level in each of our 100+ categories. Special Illustration Award competition for illustrated books. Roll of high quality, embossed award stickers ($50 value). Digital award seal for your book cover and print/web marketing. Personalized award certificate. Olympics-style physical award medal with ribbon. Awards ceremony with guest speakers and media coverage. Book displayed in our booth at the largest book fair in America. Book review posted on 7 popular book and social networking sites.

Feedback? Mini-critique of 5 key areas of your book.

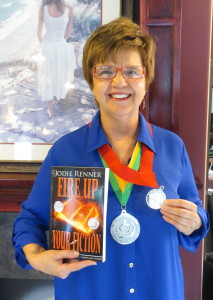

FAPA PRESIDENT’S BOOK AWARDS

Sponsored by: Florida Authors and Publishers Association

Requirements: English language titles published in 2014 or 2015. Any author or publisher who resides in North America may enter. Bound books only, except for one category: e-books. Send four copies of your book for each category entered (e.g. one book entered in three categories = 12 copies of the book).

Fee: Until March 1: $75 (non-members), $65 (members); $50 for each additional category; After March 1: $85 (non-members), $75 (members); $50 each additional category

Deadline: May 1, 2015

Categories: 30

Awards: FAPA will award one Gold Medal and up to two Silver Medals in each category. Winners receive: a gold or silver medal, a certificate, decals for book covers, and publicity.

Written review by judges: No

~ 2015 KINDLE BOOK AWARDS

Deadline: May 1, 2015

Details: Open to all independent and small press authors. For eBooks published on Amazon between May 1, 2013 – May 1, 2015 (Must have Amazon Link).

Fee: $29 (Use Code SJC85 before April 1st for 10% Early Bird Discount)

Categories: Mystery/Thriller, Romance, Y/A, Sci-fi/Fantasy, Literary Fiction, Horror/Suspense, Non-Fiction

Awards: 7 category winners will receive $350 cash, and $900+ in promotion & tools

~ THE ERIC HOFFER AWARD

Deadlines: Books: January 21, 2015. Short prose: March 31, 2015.

Fees: Books: $55

Categories: 18 categories

Prizes: Two grand prizes, one for short prose (i.e. fiction and creative nonfiction) and one for independent books. Prizes include a $250 award for short prose and a $2,000 award for best independent book. In addition, various other honors and distinctions are given for both prose and books.

Judges provide feedback/commentary on all books submitted? No. “Our judging process is a three tier system. Two successive category judges score the book on a seven point criteria system and provide feedback before it is passed to the higher level judges, but we do not provide feedback to the authors / publishers / nominators. We did in the early years, but it resulted in too many authors feeling the need to defend their books.”

~ SHELF UNBOUND WRITING COMPETITION FOR BEST SELF-PUBLISHED BOOK

Sponsored by: Shelf Media Group, Half Price Books

Eligibility: Any independently published book in any genre is eligible for entry.

Deadline: Oct. 1, 2015.

Entry fee: $40 per book.

Submission: Email a PDF or Word Doc of the book or mail in a physical copy.

Details and benefits: Top five books receive editorial coverage in the December/January 2016 issue of Shelf Unbound. The author of the book named as the Best Independently Published book will receive editorial coverage as well as a year’s worth of full-page ads in Shelf Unbound (rate card value $6,000). More than 100 books deemed by the editors as “notable” entries in the competition will also be featured in the December/January 2016 issue of Shelf Unbound.

Judges provide feedback/commentary on all books submitted? No.

OTHER BOOK AWARDS: (Click on the names.) Beverly Hills Book Awards, Bookworks Awards, eLit Book Awards, EPIC eBook Competition, Global eBook Awards, Green Book Festival, Nautilus Book Awards, Publishing Innovation Awards, Reader Views Literary Awards

BOOK FESTIVAL CONTESTS: New England Book Festival, New York Book Festival, San Francisco Book Festival, The Beach Book Festival, The Hollywood Book Festival, London Book Festival, Paris Book Festival, The Living Now Book Awards

INTERNATIONAL: International Book Awards, The International Rubery Book Award, The WISHING SHELF Independent Book Awards [UK]

CHILDREN’S BOOKS: The Moonbeam Children’s Book Awards

Can you think of any more to add? Have you had any experiences with any of these book contests that you’d like to share? Let us know in the comments below. Thanks!

Jodie Renner is a freelance editor and the award-winning author of three craft-of-writing guides in her series An Editor’s Guide to Writing Compelling Fiction: Fire up Your Fiction, Writing a Killer Thriller, and Captivate Your Readers. Fire up Your Fiction was awarded a silver medal from FAPA President’s Book Awards, a silver medal from Readers’ Favorite Awards, and an Honorable Mention from Writer’s Digest awards. Find Jodie at www.JodieRenner.com, www.JodieRennerEditing.com, and on Facebook and Twitter.

Jodie Renner is a freelance editor and the award-winning author of three craft-of-writing guides in her series An Editor’s Guide to Writing Compelling Fiction: Fire up Your Fiction, Writing a Killer Thriller, and Captivate Your Readers. Fire up Your Fiction was awarded a silver medal from FAPA President’s Book Awards, a silver medal from Readers’ Favorite Awards, and an Honorable Mention from Writer’s Digest awards. Find Jodie at www.JodieRenner.com, www.JodieRennerEditing.com, and on Facebook and Twitter.

Jodie Renner, editor & author @JodieRennerEd

Jodie Renner, editor & author @JodieRennerEd For more tips on pacing your scenes, including how to write effective action scenes, check out my three editor’s guides to writing compelling fiction: Captivate Your Readers, Fire up Your Fiction, and Writing a Killer Thriller.

For more tips on pacing your scenes, including how to write effective action scenes, check out my three editor’s guides to writing compelling fiction: Captivate Your Readers, Fire up Your Fiction, and Writing a Killer Thriller.