I moved into my new place last week. Hence why you haven’t seen me in the comment section. It took two weeks to pack. I’m now unpacking. I found a cozy little abode on the New Hampshire seacoast, near the Massachusetts border. It’s the best of both worlds — two minutes from anything I might need, yet a quiet country setting with plenty of wildlife.

As I gazed out my kitchen window for the first time, five huge male turkeys stood sentinel in the yard. Soon, twenty-five more joined them to socialize, feast, and play. The original five Toms guard the property all day. There’s also an adorable opossum and three albino skunks — stunning all white fur — who come nightly to eat alongside the resident stray cat. All four share the same bowl.

Why can’t humans put aside their differences like animals can?

For my fellow crow lovers out there, a murder of crows arrived on day two. Or Poe and the gang followed me. Sure sounds like Poe’s voice, but I can’t be certain until I set up their feeding spot and take a closer look. My murder has white dots, each in different spots, which helps me tell them apart. Plus, Poe has one droopy wing.

As I watched the five Toms this morning, it reminded me of a post I’d written back in 2017 (time flies on TKZ, doesn’t it?). So, I thought I’d revamp that post a bit, and tweak for our pantser friends.

***

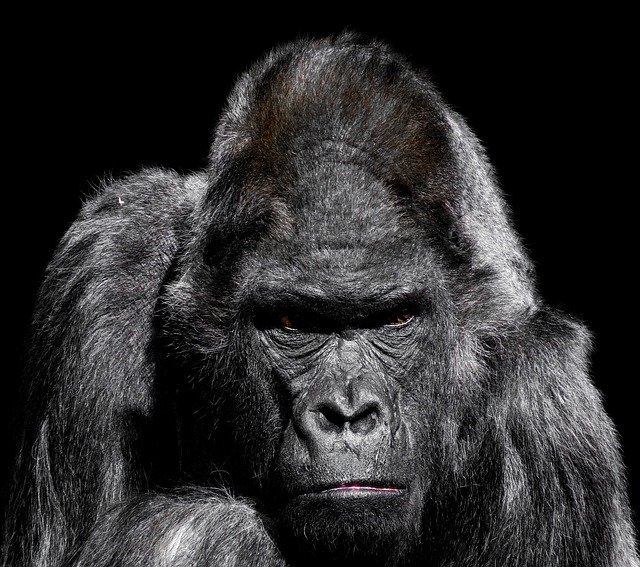

Clare’s recent post got me thinking about craft and how, as we write, the story inflates like a Tom turkey. If you think about it long enough and throw in a looming deadline, Tom Turkey and story structure have a lot in common.

Stay with me. I promise it’ll make sense, but I will ask you to take one small leap of faith — I need you to picture Tom Turkey as the sum of his parts, constructed by craft. And yes, this light bulb blazed on over the Thanksgiving holiday. We are now having spiral ham for Christmas dinner.

But I digress.

Story beats build Tom’s spine. Think of each milestone as vertebrae. Pantsers, let the story unfold as it flows. You can always check the beat placement after the drafting stage.

The ribs that extend from Tom’s spine liken to the equal parts that expand our beats and tell us how our characters should react before, during, and after the quest.

Broken into four equal parts, 25% percent each, this is the dramatic arc. It’s a natural progression that many writers do instinctually. If you want to check your work after the drafting stage, pantsers, the dramatic arc should look like this…

- Setup (Page 1 – 25% mark): Introduce protagonist, hook the reader, setup First Plot Point through foreshadowing, stakes, and establish empathy (not necessarily likability) for the MC.

- Response (25% – 50% mark): The MC’s reaction to the new goal/stakes/obstacles revealed by the First Plot Point. MC doesn’t need to be heroic yet. They retreat, regroup, and have doomed attempts at reaching their goal. Also include a reminder of antagonistic forces at work.

- Attack (50% – 75% mark): Midpoint information/awareness causes the MC to change course in how to approach the obstacles; the hero is now empowered with information on how to proceed, not merely reacting anymore.

- Resolution (75% – The End): MC summons the courage, inner strength, and growth to find a solution to overcome inner obstacles and conquer the antagonistic force. All new information must have been referenced, foreshadowed, or already in play by 2nd Plot Point or we’re guilty of deus ex machina.

Tom Turkey is beginning to take shape.

Characterization adds meat to his bones, and conflict-driven sub-plots supply tendons and ligaments. When we layer in dramatic tension in the form of a need, goal, quest, and challenges to overcome, Tom’s skin forms and thickens.

With obstacle after obstacle, and inner and outer conflict, Tom strengthens enough to sprout feathers. At the micro-level, MRUs (Motivation-Reaction-Units) — for every action there’s a reaction — establish our story rhythm and pace. They also help heighten and maintain suspense. If you remember every action has a reaction, MRUs come naturally to many writers. Still good to check on the first read through.

MRUs fluff Tom Turkey’s feathers. He even grew a beak!

Providing a vicarious experience, our emotions splashed across the page, makes Tom fan his tail-feathers. The rising stakes add to Tom’s glee (he’s a sadist), and he prances for a potential mate. He believes he’s ready to score with the ladies. Tom may actually get lucky this year.

Then again, we know better. Don’t we, dear writers? Poor Tom is still missing a few crucial elements to close the deal.

By structuring our scenes — don’t groan, pantsers! — Tom grew an impressive snood. See it dangling over his beak? The wattle under his chin needs help, though. Hens are shallow creatures. 😉 Quick! We need a narrative structure.

Narrative structure refers to the way in which a story is organized and presented to the reader. It includes the plot, subplot, characters, setting, and theme, as well as techniques and devices used by the author to convey these elements.

Now, Tom looks sharp. What an impressive bird. Watch him prance, full and fluffy, head held high, tail feathers fanned in perfect formation.

Uh-oh. Joe Hunter sets Tom in his rifle scope. We can’t let him die before he finds a mate! But how can we save him? We’ve already given him all the tools he needs, right?

Well, not quite.

Did we choose the right point of view to tell our story? If we didn’t, Tom could wind up on a holiday table surrounded by drooling humans in bibs. We can’t let that happen! Nor can we afford to lose the reader before we get a chance to dazzle ’em.

Tom needs extra oomph — aka Voice. Without it, Joe Hunter will murder poor Tom.

Voice is an elusive beast for new writers because it develops over time. To quote JSB:

It comes from knowing each character intimately and writing with the “voice” that is a combo of character and author and craft on the page.

That added oomph makes your story special. No one can write like you. No one. Remember that when self-doubt or imposter syndrome creeps in.

If Tom hopes to escape Joe Hunter’s bullet, he needs wings in the form of context. Did we veer outside readers’ expectations for the genre we’re writing in? Did we give Tom a heart and soul by subtly infusing theme? Can we boil down the plot to its core story, Tom’s innards? What about dialogue? Does Tom gobble or quack?

Have we shown the three dimensions of character to add oxygen to Tom’s lungs? You wouldn’t want to be responsible for suffocating Tom to death, would you?

- 1st Dimension of Character: The best version of who they are; the face the character shows to the world

- 2nd Dimension of Character: The person a character shows to friends and family

- 3rd Dimension of Character: The character’s true character. If a fire breaks out in a crowded theater, will they help others or elbow their way to the exit?

Lastly, Tom needs a way to wow the ladies. Better make sure our prose sings. If we don’t, Tom might die of loneliness. Do we really want to be responsible for that? To be safe, let’s review our word choices, sentence variations, paragraphing, white space, grammar, and how we string words together to ensure Tom lives a full and fruitful life.

Don’t forget to rewrite and edit. If readers love Tom, he and his new mate may bring chicks (sequels or prequels) into the world, and we, as Tom’s creator, have the honor of helping them flourish into full-fledged turkeys.

Aww… Tom’s story has a happy ending now. Good job, writers!

For fun, choose a name for Tom’s mate. Winner gets bragging rights.