By John Gilstrap

Happy Wednesday, everyone. Today, we take on the work of a brave writer who submitted his first few hundred words for some input. First, I’ll present the piece as I received it, and then my comments will be on the flip side, after the asterisks.

The Mirage

Chapter One

Mexican State of Zacatecas

Chihuahuan Desert

The caravan of seven black SUVs drove through the empty desert. The road they followed was little more than a ribbon of heat-cracked asphalt winding through the barren, rolling hills.

Captain Jaime Barrios stood half-way through the open sunroof of the lead vehicle, a pair of binoculars pressed against his aviator sunglasses. His dark mustache hugged lips made puffy through hours of gun chewing. Scorching sun made the letters ATF gleam yellow against the back of his navy blue jacket.

A voice squawked from the radio bud he’d jammed into his ear.

“Captain Barrios. This holding mode is holding a little long, no?”

Barrios thumbed the mike button at his lapel before giving a curt reply.

“We’ll be going kinetic in another minute. Just sit tight.”

He looked to the three other cars in the front of the caravan. Two of them had Special Response agents also standing out of their car sunroofs. Each wore a bullet proof vest and carried an M4 assault rifle slung. The other agents inside the SUVs were similarly armed and armored.

The radio crackled in his ear again.

“Captain,” one of the agents complained, “No one said this raid came with a side of skin cancer.”

Barrios smiled mirthlessly as he continued to scan the desert. “Ha. The Chihuahuan desert welcomes your Boston ass, McKinney.”

“Shit. Who needs a fuckin’ border wall when you have this sun?”

A gleam from far behind caught Barrios’ attention. Dark dots appeared against the bright yellow landscape, growing larger with each second. His pulse quickened as he realized that their waiting was over.

“They’re coming up at six o’clock. Everyone, get ready. It’s game time.”

Barrios stamped his foot twice. At the signal, his driver accelerated. The force of the wind grew as he tucked away the binoculars and readied his assault rifle.

“Fuck,” he swore. “This looks like a lot more than eight bikes!”

“No kidding,” McKinney put in. “I count seventeen crotch rockets.”

The Hayabusa 950 motorcycles ate up the distance between them and the SUVs. Fourteen of the cyclists wore all black from head to toe. Three others had brown, yellow, or gray helmets.

Power windows rolled down on each SUV. Men poked their heads out or leaned out the windows, rifles or pistols at the ready. Barrios waited until the motorcycles were within range.

“Open fire!” he yelled into his radio.

*****

Gilstrap again. Okay, there’s a lot to like in this piece. I think the author chose an interesting place to start the story–certainly none of the throat clearing that I talked about in a piece I critiqued a few weeks ago. The prose is reasonably crisp, and the descriptions of the desert mostly work for me.

That said, I think are serious plot issues. This reads to me a bit like a reimagination of the 1960s television show, “The Rat Patrol,” where a tiny squad of six (?) guys, all in different (but very cool) uniforms drive aimlessly through the North African desert looking for fights with Nazi tanks. I loved it as a kid. I’ve since watched it as an adult. Lots of WTFing in every episode.

I’m kind of in that same place with these first pages of THE MIRAGE. I’ll stipulate that ATF agents are trolling the deserts of Mexico (though my ATF buddies tell me that such would rarely if ever be done). What bothers me most is the lack of planning and the lack of discipline. Federal agents of all ilk are buttoned down tight in these kinds of operations. The chit-chat on the radio would be a huge no-no. Even in the fire service, that was a no-no. The whole world listens in on radio traffic.

We don’t yet know what this mission is, but it is inconceivable to me that they would not have some sort of air assets in place to know what was coming at them. The SRT is one hell of a polished team. Like all such teams, they pride themselves in denying their opposition forces anything that remotely resembles a fair fight.

Then there’s the whole notion of firing without being fired upon. That’s just not done. And if it were done, shooting moving targets from a moving platform is a recipe for disaster, especially given the lack of clear firing lanes.

If this is the beginning of a serious book that the author wants to be taken seriously, lots of research remains to be done. A good place to start is to embrace the fact that anything you’ve seen in any movie in the “Fast ‘n’ Furious” franchise ranks high on the wouldn’t-ever-happen scale.

Now, let’s get down to some line-level stuff . . .

The caravan of seven black SUVs drove through the empty desert. The road they followed was little more than a ribbon of heat-cracked asphalt winding through the barren, rolling hills.

Details matter. Seven black BMW X5s paints a different picture and leaves a different impression than seven black Suburbans or seven black Escalades. Also, is there a way to combine these two sentences into one? Something like, “The seven-Suburban motorcade sped through the barren, rolling desert hills on a ribbon of road that was little more than crumbled asphalt.”

Captain Jaime Barrios stood half-way through the open sunroof of the lead vehicle, a pair of binoculars pressed against his aviator sunglasses.

This is pure “Rat Patrol.” Why would he do this? It’s hot and windy and car windows are clear. Also, the current tacti-cool look is Oakley shades. The aviators remain popular mostly among older generations. That said, it’s really hard to get a good image through binoculars while wearing any form of glasses.

Also, how far out the hatch is he? He’s standing on the center console, right?

Finally, how certain are you that the ATF has captains within their rank structure? As far as I know, they’re all variants of the rank of “special agent.”

His dark mustache hugged lips made puffy through hours of gun chewing. Scorching sun made the letters ATF gleam yellow against the back of his navy blue jacket.

For the sake of argument, I will assume that the author really meant “gum chewing” because gun chewing leads to explosions of brain pizza. That said, I’m not familiar with gum chewing causing swollen lips. Assuming that Barrios is wearing the ubiquitous G-man windbreaker, I believe the letters are yellow whether seen in the sun or by candlelight.

A voice squawked from the radio bud he’d jammed into his ear.

“Jammed” is the wrong verb here. That would hurt.

“Captain Barrios. This holding mode is holding a little long, no?”

Note the comment above about the captain thing. This bit of dialogue is exclusively for the reader. Everyone in the scene knows exactly how long they’ve been there, so what is the motivation in asking this? Also, it’s chit-chat. Finally, I don’t get the “holding mode” here. Seems to me they’re on the way to somewhere.

Barrios thumbed the mike button at his lapel before giving a curt reply.

The appropriate spelling is “mic” when you mean microphone. I’m getting conflicting information throughout this piece about their wardrobe. Assuming they’re wearing ballistic armor, “lapels” don’t really exist.

“We’ll be going kinetic in another minute. Just sit tight.”

So, now the bad guys know the good guys’ plan–because they transmitted it over the radio. I’m confused as to how Barrios knows this already. If what we’re reading here is a mission to murder the folks on the crotch rockets, you’d do well to set it up in some narrative.

He looked to the three other cars in the front of the caravan.

There’s a lot here. From one paragraph to another, the SUVs became cars. How?

Two of them had Special Response agents also standing out of their car sunroofs.

This paints a picture of two sedans, each with multiple agents standing out to the sunroof. I’m think clown car.

When you write “Special Response agents” I presume you mean agents assigned to the Special Response Team, the elite of the elite within ATF. If so, I would point that out.

Each wore a bullet proof vest and carried an M4 assault rifle slung. The other agents inside the SUVs were similarly armed and armored.

“Bullet proof vests” do exist in the real world, but I’m certain that’s not what your guys are wearing. Your team is probably wearing “ballistic armor.”

Let’s talk about those slung M4s. Question One: Why are they slung? When you’re driving into a gunfight, you want to enter it with your weapon fully prepared for deployment. “Slung” generally means “at ease.” Question Two: Since slung rifles are carried with muzzles facing down (remember, our guys are doing the prairie dog peek out of their vehicles), I see the muzzle pointing at the driver’s ear. That would be disconcerting.

The radio crackled in his ear again.

This could be merely stylistic, but to my ear, radios haven’t “crackled” in decades. To my ear, they “pop” or “break squelch.”

“Captain,” one of the agents complained, “No one said this raid came with a side of skin cancer.”

I think the author is going for lighthearted banter here, but it comes off as whining.

Barrios smiled mirthlessly as he continued to scan the desert. “Ha. The Chihuahuan desert welcomes your Boston ass, McKinney.”

Now I see the source of the lack of discipline. It starts at the top. For the world to hear. And surely there’s a better word than mirthlessly.

“Shit. Who needs a fuckin’ border wall when you have this sun?”

Got it. Maybe they’d be cooler if they took off those jackets.

Most importantly: Beware the F-bombs. I did a whole video for my YouTube channel on the perils of using high-end profanity in popular fiction. It turns off an astonishing number of readers. I used to be an offender, but after literally hundreds of letters and emails from readers, I stopped. I haven’t written an F-bomb in probably my latest 15 books. These are hard-edged thrillers, and no one has ever complained that the bad language isn’t there.

A gleam from far behind caught Barrios’ attention.

Be specific. “Far behind” means nothing.

Dark dots appeared against the bright yellow landscape, growing larger with each second. His pulse quickened as he realized that their waiting was over.

I get that the author is playing coy here, but for me it’s too coy by half. I’d like to know who these people are–if not by specific identity, then by a throw-away reference to why it’s important to engage them.

“They’re coming up at six o’clock. Everyone, get ready. It’s game time.”

Barrios stamped his foot twice. At the signal, his driver accelerated.

So, everything else can go out on the air, but he has to stomp his foot to say “go faster”?

The force of the wind grew as he tucked away the binoculars and readied his assault rifle.

I have no idea what this means. Where did he tuck the binoculars? No one thinks of their weapon as an “assault rifle” and what readying does he need to do? He’s going to war here, so it seems a little late to oil the action. He’d probably think of the weapon as his M4 or his Colt (the manufacturer that supplies ATF with their M4s). By the time Barrios peeked his noggin out of the hole, he’d have the puppy chambered and ready to go. One quick move of his thumb against the safety lever, and he’d he ready to rock.

“Fuck,” he swore. “This looks like a lot more than eight bikes!”

“No kidding,” McKinney put in. “I count seventeen crotch rockets.”

The Hayabusa 950 motorcycles ate up the distance between them and the SUVs. Fourteen of the cyclists wore all black from head to toe. Three others had brown, yellow, or gray helmets.

Here again, the author is presenting information through dialogue that is really for the benefit of the reader. They’ve come a long way from seeing barely discernable black dots to a specific count of precisely 17 Hayabusa 950 motorcycles, plus a breakdown of their wardrobe.

But wait! As we’ll see below, McKinney got all of these details BEFORE they were in range of the M4s. That would put them at at least 200 yards. I want McKinney’s ophthalmologist!

Power windows rolled down on each SUV. Men poked their heads out or leaned out the windows, rifles or pistols at the ready. Barrios waited until the motorcycles were within range.

The clown car image has returned. Brave author, I urge you to go to your car and act this image out. The bad guys are screaming up from behind (from “six o’clock”). Imagine being packed into your vehicle with all the gear. Some people are “leaning out” of windows, others are only showing their heads. And they all want to shoot the same direction.

“Open fire!” he yelled into his radio.

Yelling into the radio does not extend the range of the signal, but it does garble the transmission. Yelling into radios is unprofessional.

Okay, Brave Author, I’ve been hard on you, but know that it comes from a helpful place. I’m on the record here and elsewhere stating that “write what you know” is perhaps the worst advice ever given, but this is an example of when the advice spot-on.

When a writer enters the world of weapons and tactics (or technology or space flight or any one of thousands of topics that people think they know but probably don’t), little mistakes add up quickly.

Okay, TKZers. Your turn.

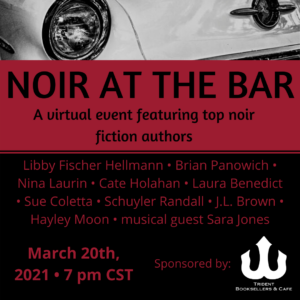

Join me, Laura Benedict, and many others on Zoom for Noir at the Bar.

Join me, Laura Benedict, and many others on Zoom for Noir at the Bar.

Dr. Edmund Locard was a French scientist from the early 1900s. He pioneered modern crime scene processing and was known as the real Sherlock Homes of scientific sleuthing. Locard’s mantra was, “Every contact leaves a trace.” This simple phrase was so profound that famed criminalist Dr. Paul. L. Kirk of the National Academy of Forensic Sciences put Locard’s this way:

Dr. Edmund Locard was a French scientist from the early 1900s. He pioneered modern crime scene processing and was known as the real Sherlock Homes of scientific sleuthing. Locard’s mantra was, “Every contact leaves a trace.” This simple phrase was so profound that famed criminalist Dr. Paul. L. Kirk of the National Academy of Forensic Sciences put Locard’s this way: Crime scene examination and trace evidence conclusion categories are uniform in the western criminal investigation field. Trace evidence probative value is rated on a conclusion scale set forth by the American Society of Crime Laboratory Directors Laboratory Accreditation Board and ANSI-ASQ National Accreditation Board / FQS. The Scientific Working Group for Material Analysis

Crime scene examination and trace evidence conclusion categories are uniform in the western criminal investigation field. Trace evidence probative value is rated on a conclusion scale set forth by the American Society of Crime Laboratory Directors Laboratory Accreditation Board and ANSI-ASQ National Accreditation Board / FQS. The Scientific Working Group for Material Analysis

The evidentiary test at trial is then threefold. Trace or fragmentary evidence has to be relevant, have probative value, and not be prejudicial to the accused person or to the proceeding itself. Relevancy is a straightforward concept. The trace evidence has to someway connect the accused to the crime. There has to be a nexus that’s relevant.

The evidentiary test at trial is then threefold. Trace or fragmentary evidence has to be relevant, have probative value, and not be prejudicial to the accused person or to the proceeding itself. Relevancy is a straightforward concept. The trace evidence has to someway connect the accused to the crime. There has to be a nexus that’s relevant.

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a coroner processing forensic evidence in death investigations. Now, Garry is a crime writer and indie publisher with sixteen books to his credit. His latest in the Based-On-True-Crime Series by Garry Rodgers is

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a coroner processing forensic evidence in death investigations. Now, Garry is a crime writer and indie publisher with sixteen books to his credit. His latest in the Based-On-True-Crime Series by Garry Rodgers is