by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

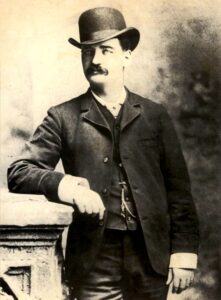

Bat Masterson, c. 1880

Back when the West was very young

There lived a man named Masterson.

He wore a cane and derby hat,

They called him Bat, Bat Masterson!

During the “golden age of television,” the 1950s and early 60s, the Western was the dominant genre. You had The Lone Ranger, Gunsmoke, Roy Rogers, Maverick, Rawhide, Bonanza, Sugarfoot, Have Gun Will Travel, Wyatt Earp, Tombstone Territory, Death Valley Days, Cheyenne…and on and on. Among them was a series starring Gene Barry as Bat Masterson. The lyrics at the top of this post are from the song that accompanied the series.

Interesting historical item: Bartholomew “Bat” Masterson should be better known to us as a writer!

It is true he was an Old West lawman and friend of Wyatt Earp. But his legend as a gunslinger was the result of a practical joke played upon a naïve young newspaperman.

In the 1880s readers in the East were enamored of tales of derring-do out West. Savvy writers were quick to exploit that fascination. Ned Buntline, for example, created the legend of Buffalo Bill Cody. Cody himself would ride that publicity into a nice income from his Wild West Show.

In 1881 a reporter named Young, who wrote for the New York Sun, came out to the Colorado mining town of Gunnison, looking for a “shoot-’em-up” story for the paper. He asked one of the locals, a man named Cockrell, where he might start looking for such a story. Cockrell decided to have some fun with the dude. He spun a tale of a lawman he knew from Dodge City, a twenty-seven-year old named Bat Masterson. Why, he’d already killed twenty-six men! And seven of those were to avenge the murder of his brother! Another time he hunted down two Mexican outlaws and brought their heads back to prove it and collect the bounty! And so on. Young lapped it all up and filed the story. The Masterson legend took off, never to be ameliorated. (In fact, Masterson the lawman killed only two men. One of them was, indeed, the murderer of his brother.)

Times changed. The era of the gunslinger came to an end. Bat Masterson, who was more a gambler and “sport” than anything else, ended up in Denver as a promoter of the sport of boxing. This was in the bare-knuckles era, and Masterson would be intimately involved with every heavyweight championship fight until his death in 1921.

His time in Denver did not prove profitable, so in 1902 he and his wife headed for the more promising venue of New York City.

His arrival was not propitious. The second day he was there he was getting his shoes shined at a stand when the cops, led by an officer named Gargan, arrested him. Why? Because he was nicely dressed and happened to be near a West Coast gambler by the name of Sullivan. It was Sullivan and some others who were part of a bunco scheme to fleece a Mormon elder named Snow out of $16,000. Masterson did not take his arrest well. His loud protestations at the station were muted somewhat when police removed a concealed revolver from their famous arrestee. Snow failed to identify Masterson, and the bunco charge was dropped. Masterson, however, had to pay a fine of $10 for the concealed weapon.

Never one to take it on the chin, Masterson filed suit against Snow for injury to his good name, to the tune of $10,000. Snow settled with him out of court. Masterson never forgot Gargan, either. Eleven years later he would seek a charge against Gargan for perjury in his testimony about the 1902 arrest.

Masterson in NYC, c. 1920

Did I mention that Masterson was pugnacious? That was one of the qualities that made his column in the New York Morning Telegraph so popular. From 1903 to 1921 the former lawman wrote three columns a week and gained a huge following all over America. He didn’t cheat on the verbiage, either. His pieces averaged 1700 words. Mostly he wrote about boxing, but he was not averse to sharing his opinions on other matters of the day.

Masterson was frontier educated and never went to college. So how did he master the art of writing? Three ways. First, he was a voracious reader. Second, he made it a goal to expand his style by adding to his vocabulary on a regular basis. And last, but not least, he let his passion for his subject bleed onto the page. For example, in 1911 he covered a fight between a boxer named Burke and an Irishman named Maher. Burke, he wrote, found Maher “a fine bit of cheese” who threw wild punches. But after a Maher haymaker “put a crack in the air,” Burke “planted a left into the Irishman’s potato pit … and it was curtains for Erin’s representative.”

So the writing lesson for today we’ll call the Masterson Triad:

- Read widely

- Expand your style

- Make sure your passion is evident on the page

One last bit of trivia. Have you seen the musical Guys and Dolls? Most probably you have. It was a big Broadway hit, and then a hit movie. Based on characters created by Damon Runyon, it is the fanciful story of Broadway touts and gamblers with names like Harry the Horse, Nicely-Nicely Johnson, Society Max, and Benny Southstreet. The leading figures are Nathan Detroit (Frank Sinatra in the movie version) and Sky Masterson (Marlon Brando). The plot is based on a bet between Nathan and Sky. The two are sitting in a restaurant on Broadway when Nathan bets Sky that he will not be able to take a “doll” of Nathan’s choosing out to dinner in Havana, Cuba, the following night. Sky, who believes all dolls are the same, takes the bet.

At which point Nathan points outside to Sergeant Sarah Brown of the Salvation Army!

Here is the interesting backstory. Damon Runyon was a young reporter whom Bat Masterson took under his wing. The two remained close until Masterson’s death in 1921. One day they were sitting in a bar, and Masterson was spinning tales about gambling and guns, when they heard a loud thumping out in the street. It was the bass drum of a Salvation Army band, summoning sinners to a meeting. The band was led by a fetching young woman. And Runyon immediately got a story spark: what if a pristine Salvation Army sergeant fell in love with a sport like Bat Masterson?

The idea stuck, and years later Runyon wrote “The Idyll of Miss Sarah Brown.” The sport he named Sky Masterson, in honor of his old friend. The story became the basis for Guys and Dolls.

Let’s ask the Bat Masterson questions today.

- Do you read widely?

- Are you purposeful in expanding your style?

- How do you get passion onto your pages?

Note: Most of the research for this post is taken from Robert K. DeArment, Gunfighter in Gotham: Bat Masterson’s New York City Years, University of Oklahoma Press, 2013.