by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Mel Brooks and Carl Reiner had a routine called The 2000-Year-Old Man. Reiner played a reporter interviewing the world’s oldest man, who would tell him all sorts of things that happened in the distant past. One time the subject was religion:

Mel Brooks and Carl Reiner had a routine called The 2000-Year-Old Man. Reiner played a reporter interviewing the world’s oldest man, who would tell him all sorts of things that happened in the distant past. One time the subject was religion:

REINER: Did you believe in anything?

BROOKS: Yes, a guy, Phil. Philip was the leader of our tribe.

REINER: What made him the leader?

BROOKS: Very big, very strong, big beard, big arms, he could just kill you. He could walk on you and you would die.

REINER: You revered him?

BROOKS: We prayed to him. Would you like to hear one of our prayers? “Oh Philip. Please don’t take our eyes out and don’t pinch us and don’t hurt us. Amen.”

REINER: How long was his reign?

BROOKS: Not too long. Because one day, Philip was hit by lightning. And we looked up and said, “There’s something bigger than Phil.”

I’ll return to this later.

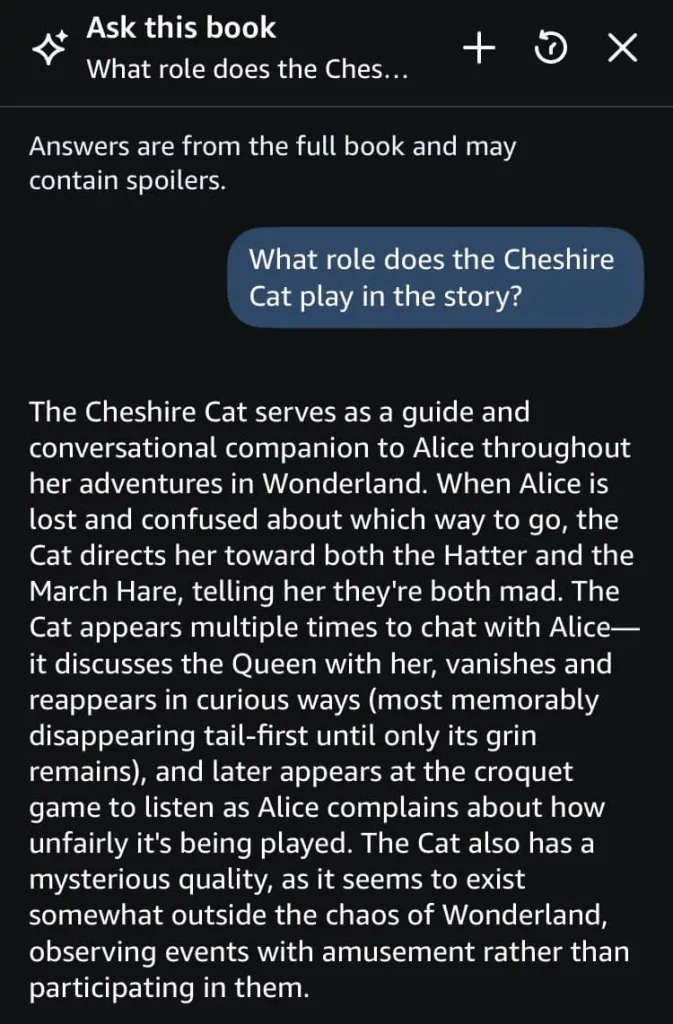

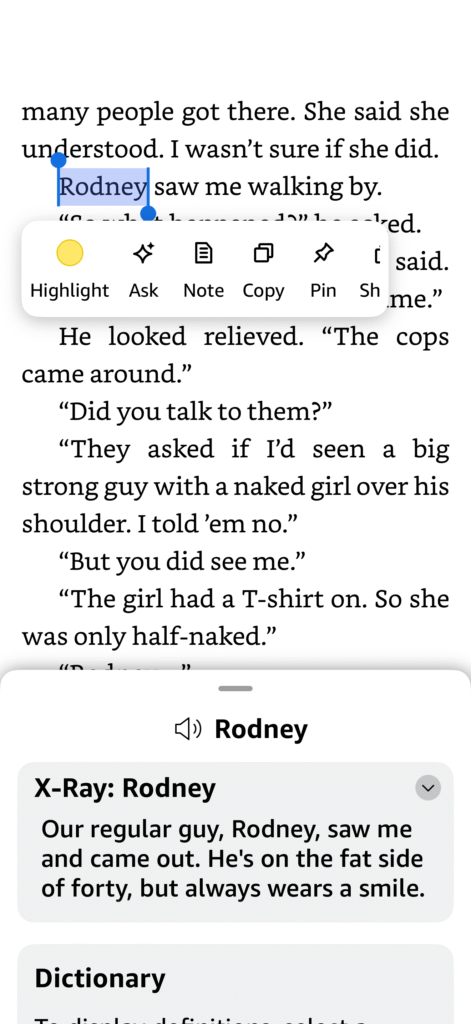

I was too busy to give a thoughtful reply to Terry’s post about Amazon and their new “Ask This Book” feature. Enough has been said about it there—and everywhere—that the issues are clear.

Most pressing for authors and publishers are copyright and permission. Does this feature, which provides plot summaries and character analyses, violate copyright? Or is it more like a flexible version of CliffsNotes?

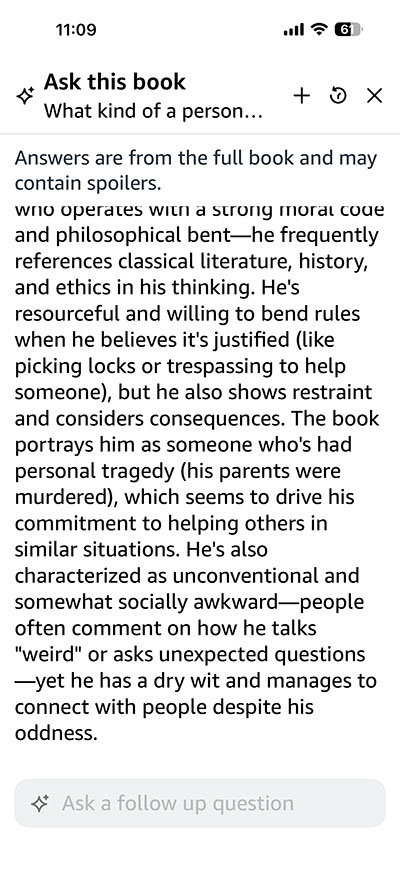

Or is ATB different in kind? The Authors Guild thinks so. It argues that what Amazon is doing is creating an interactive book from the original material, i.e., another iteration of an author’s intellectual property, for which the author should receive compensation. I suspect there is a lot more to come on this matter.

It should be noted that someone can go straight to AI now and ask for a summary and analysis of a book. I went to Grok and asked for a summary of a thriller by one of my favorite authors. I got it. Accurately, too. Without spoilers. When I asked specifically for the spoiler answer to the ultimate mystery, I got that, too. I then asked for an analysis of the main characters. Check. (In deference to the author, from whom I did not seek permission, I will not post the answers.) Is ATB merely a more convenient way for a reader to get the same information?

And speaking of permission, this feature is being rolled out by Amazon without giving the author or publisher the choice to opt in or out, as with DRM. This has raised the temperature in many a discussion. Given that, what should an author do? I don’t think many will pull their ebooks off Amazon in protest, because Amazon is their biggest revenue stream. It’s irrelevant whether one is wide or exclusive.

Which brings me back to Phil. Because there’s something bigger than Amazon in all this. And that is Artificial Intelligence itself. We all know it’s here, it’s growing, and it’s here to stay. There have been innumerable discussions, debates, and jeremiads on how writers use this borg. For me, the firm no-go zone is having it generate text that is cut-pasted into a book, even though AI can now replicate a writer’s particular style (see Joe Konrath’s recent post and the examples therein).

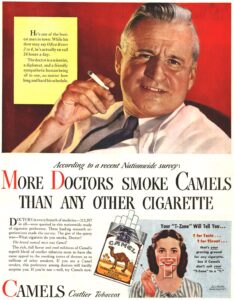

What I’m most concerned about is the larger issue of melting brains. Using AI as a substitute for hard thinking atrophies the gray matter. “Use it or lose it” is real. In the past, a reader who wanted to know what’s happened in a book had to “flip back” actual pages to find out. That was work, and therefore good for the noggin. AI bypasses that neural network.

This brain rot is bad for the species, especially among the young. It tears my heart out to see a man or woman walking down the street, looking at their phone, while pushing a stroller with a toddler in it, who is likewise staring at a device full of dancing monkeys or pink rabbits. That child’s brain is being robbed of essential foundations built only by looking around at the real world in wonder.

The school years used to be a daily session of ever more complex thinking. Learning to write a persuasive essay—with a topic paragraph and supporting arguments—was once a major goal of education. Now AI can do that for you in seconds, so you can go back to playing Candy Crush.

We all know this. But what can we do about it? Take responsibility for our own actions. Don’t let AI do all the work for us, or for our kids and grandkids.

And if you’re upset with Amazon’s ATB, cool your jets and register a polite response to KDP customer service. There’s enough vitriol out there. We’re awash in so much Ghostbusters II mood slime now that we don’t need to add to it.

Because as bad as brain rot is, soul rot is worse. And a hate-laced, click-bait habit will inevitably turn your soul into the picture of Dorian Gray. Don’t go there.

And those are my myriad thoughts. Help me sort them out in the comments.