James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Back when I was pounding the Off-Broadway boards I got a bit part in a production of Othello. I got to wear tights and say Shakespeare things.

Our Othello was the marvelous stage actor Earle Hyman, better known to most of you as Bill Cosby’s father on The Cosby Show. In point of fact Earle is one of the great Othellos. He is also a very nice man.

Once we were chatting backstage and I told him that someday I would love to play Iago. He said I would be perfect for it because I had such an open, honest face (this was before I went to law school). That, after all, is what makes Iago powerful. Othello calls him “My friend … honest, honest Iago.” And if the part is played right there is even a touch of sympathy for Iago at the end as he’s dragged off to be tortured to death.

This, in fact, is what set Shakespeare apart from his contemporaries. He knew how to mangle the emotions of the audience, even to the point of rendering some sympathy for the devil.

Dean Koontz wrote, “The best villains are those that evoke pity and sometimes even genuine sympathy as well as terror. Think of the pathetic aspect of the Frankenstein monster. Think of the poor werewolf, hating what he becomes in the light of the full moon, but incapable of resisting the lycanthropic tides in his own cells.”

All this to say that the best villains in fiction, theatre, and film are never one-dimensional. They are complex, often charming, and able to manipulate. The biggest mistake you can make with a villain is to make him pure evil or all crazy.

So what goes into crafting a memorable villain?

1. Give him an argument

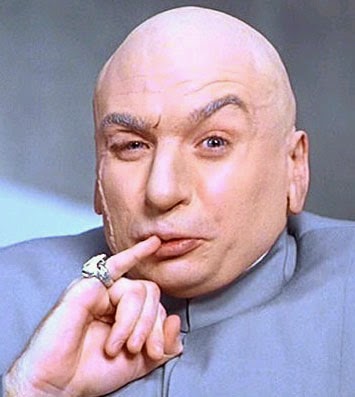

There is only one character in all storytelling who wakes up each day asking himself what fresh evil he can commit. This guy:

But other than Dr. Evil, every villain feels justified in what he is doing. When you make that clear to the reader in a way that approaches actual empathy, you will create cross-currents of emotion that deepen the fictive dream like virtually nothing else.

One of the techniques I teach in my workshops is borrowed from my courtroom days. I ask people to imagine their villain has been put on trial and is representing himself. Now comes the time for the closing argument. He has one opportunity to make his case for the jury. He has to justify his whole life. He has to appeal to the jurors’ hearts and minds or he’s doomed.

Write that speech. Do it as a free-form document, in the villain’s voice, with all the emotion you can muster. Emphasize what’s called “exculpatory evidence.” That is evidence that, if believed, would tend to exonerate a defendant. As the saying goes, give the devil his due.

Note: This does not mean you are giving approval to what the villain has done. No way. What you are getting at is his motivation. This is how to know what’s going on inside your villain’s head throughout the entire novel.

Note: This does not mean you are giving approval to what the villain has done. No way. What you are getting at is his motivation. This is how to know what’s going on inside your villain’s head throughout the entire novel.

Want to read a real-world example? See the cross-examination of Hermann Goering from the Nuremberg Trials. Here’s a clip:

I think you did not quite understand me correctly here, for I did not put it that way at all. I stated that it had struck me that Hitler had very definite views of the impotency of protest; secondly, that he was of the opinion that Germany must be freed from the dictate of Versailles. It was not only Adolf Hitler; every German, every patriotic German had the same feelings. And I, being an ardent patriot, bitterly felt the shame of the dictate of Versailles, and I allied myself with the man about whom I felt perceived most clearly the consequences of this dictate, and that probably he was the man who would find the ways and means to set it aside. All the other talk in the Party about Versailles was, pardon the expression, mere twaddle … From the beginning it was the aim of Adolf Hitler and his movement to free Germany from the oppressive fetters of Versailles, that is, not from the whole Treaty of Versailles, but from those terms which were strangling Germany’s future.

How chilling to hear a Nazi thug making a reasoned argument to justify the horrors foisted upon the world by Hitler. So much scarier than a cardboard bad guy.

So what’s your villain’s justification? Let’s hear it. Marshal the evidence. Know deeply and intimately what drives him.

2. Choices, not just backstory

It’s common and perhaps a little trite these days to give the villain a horrific backstory and leave it at that.

Or, contrarily, to leave out any backstory at all.

In truth, everyone alive or fictional has a backstory, and you need to know your villain’s. But don’t just make him a victim of abuse. Make him a victim of his own choices.

Back when virtue and character were actually taught to children in school, there was a lesson from the McGuffey Reader that went like this: “The boy who will peep into a drawer will be tempted to take something out of it; and he who will steal a penny in his youth will steal a pound in his manhood.”

The message, of course, is that we are responsible for our choices and actions, and they have consequences.

So what was the first choice your villain made that began forging his long chain of depravity? Write that scene. Give us the emotion of it. Even if you don’t use the scene in your book, knowing it will give your villain scope.

3. Attractiveness

The devil is not a cloven-hoofed, red-suited, pointy-eared demon with a pitchfork. Indeed, the Bible says Satan appears “as an angel of light.” He is the most beautiful of the heavenly host. His mode is to entice, not coerce.

The same with the best villains. They are sometimes attractive through raw, worldly power (Gordon Gekko). Intellect may be their weapon (Hannibal Lecter). Or a certain way with the opposite sex (innumerable homme and femme fatales). Hitchcock’s best villains were charming and therefore disarming. They often had wit and style. (My favorite is the widow-murdering uncle played by Joseph Cotten in Shadow of a Doubt.)

Give your villain at least one attractive feature and then see what the other characters do with it.

The strength of a thriller is directly proportional to the strength of the villain. The reader has to feel that this character has got what it takes to pull the wool over the eyes of the many. And if you create a touch of empathy as well, you’ll have your storytelling hooks deeply embedded in the readers’ hearts. They’ll thank you for that by buying your next book.

What’s your approach to villain writing?

I read, studied, took notes of, ‘Plot and Structure,’ so my approach to villain writing pretty much follows your examples given here. I also like to include your, ‘pet the dog,’ scenario. I think that is very powerful and effective in creating a sense of empathy.

I appreciate that, Mark. Thanks.

In my formative years, I learned how to write villains by watching Spider-Man (the animated series). Stan Lee has this down cold. Every villain has a girlfriend, and she could be his weakness or his motivation. If I remember correctly, it first dawned on me when I was watching the Sandman, a petty thief/thug, who is trying to keep it together with his girlfriend, who only wants him to clean up his act. Then he gets turned into the Sandman and everything goes downhill. But it’s that moment of understanding–we know what drives him against the hero.

Thanks for referencing the great Stan Lee. We can learn a lot from him. Like the villain who was once good but got betrayed…and therefore chose evil.

Jim, thanks for another great post. Three great points for building the villain. I needed the reminder for point #2 – the choice to start down the path of depravity.

My approach to villain writing is to start with the premise, then build the villain’s backstory from that foundation. I’m constantly thinking “what if” for ways medical procedures could be highjacked for nefarious purposes. So my villains become all types of medical personnel. I’ve given them justification, built backstory, and made them charismatic. I need to start thinking of the process that makes them take that first wrong turn.

Thanks for another teaching moment.

That’s a great way to go, Steve. From premise right to villainy, then back to the hero. That’s the way Erle Stanley Gardner used to do it. A “what if” led to what he called “the murderer’s ladder,” basically the construction of the crime from first motivation all the way to trying to cover it up.

One of the novels I’ve been sitting on is one where I haven’t resolved the villain’s character to my satisfaction yet. I had someone beta read, asked if they felt any sympathy for the villain and the answer was “No, not at all.” That had been my impression too, but I wondered if I was just being hard on myself. But my instinct was right.

I did allude briefly to some things that happened to this villain in younger days, but clearly not enough to be effective. And, as you mention here, it’s not really enough to make a sympathetic villain if they’ve suffered some mishaps or abuse..

What I haven’t done is try out your idea of showing this villain making choices during those times that formed him into the villain of the story. That, and letting him make his final statement in court, should help me make him more 3D and a touch sympathetic.

P.S. loved the “this was before I went to law school” line. ROTFL!

BK, if I can allude to a novel I mentioned a couple of months ago, An American Tragedy. One of the things Dreiser does really well is getting us inside a character about to make a fateful decision and action. He spends considerable time showing us the temptations confronting country boy Clyde Griffiths as his more sophisticated city chums get him into booze…and later, bordellos.

Once on that path, Clyde begins exercising his choices in a more selfish manner, leading to the tragedy of the title.

It’s well worth studying this stuff!

Thanks. Got it downloaded.

Great post! And oh so relevant to me, as I’m in the pre-writing stage of my latest novel. My last novel, waiting in the wings for a rewrite, featured a very fun, powerful bad guy. Frankly, he stole the show when he was on stage. From his point of view, he was behaving logically. Ruthless to others was focused and on task to him. In the new book, I’m working on upping the sympathy quotient. This villain is pushed to the point of crazy–I don’t like crazy as an explanation of villainy, but as a consequence, it has great power. I’m keeping that in mind.

Your post also dovetails very nicely with a pair of posts over at Steven Pressfield’s site on the role of villains in the story and how Act II belongs to them–its a perfect trifecta on the craft of villainy!

Nice! Thanks for telling us about the Pressfield posts.

Excellent tips and insights, James. Haven’t we all read thrillers where the villain is poorly drawn? ((Yawn)). Yet the bad guy or girl is the second most important character in the story (maybe, at time, the premiere one). I have only one other tip to add to your list:

Your villain must be a worthy opponent.

In real life, criminals tend to be as dumb as stumps. But in fiction, if the antag isn’t the equal of the protag, you lose so much chance for interplay, gamesmanship and intrigue. A stupid, banal or emotionally blank villain is just…dull.

Right on, Kris. Stupid never wins or makes you worry, except about maybe an accident happening.

These are wonderful points. Your awesome agent, Donald Maass, also have some great exercises in Writing the Breakout Novel on building the antagonist’s side of the story as though they were the hero.

I started doing that just to make my antagonist more relatable, but happily discovered it also made plotting much easier when I knew what the antagonist was doing, and therefore, what the protagonist would have to do to counter it.

I favorite types of villains are people who have a different philosophy than us. The X Men’s Xavier vs. Magneto is a great example of this. They were best friends and agreed on almost every subject but one, and that’s what they’ve both defined their life on.

The great Mr. Maass is a treasure trove of such ideas.

I love that idea about a different philosophy. Again, justification.

This is great stuff, Jim. So many of my clients are so enamored of their protagonists that the villains are one-dimensional counterpoints to their contrived victimization fantasies. (“I could love and be loved if my horrible sister/best friend/boss/colleague/creepy high school classmate wasn’t inflicting biblical cruelties upon me every second of every day because they’re jealous of me or sexually fixated on me”). To those writers, giving the villains any human motivation or release takes necessary air out of hollow constructions of their hero-characters.

I explain that in all the best stories in their genre, the villains are just as human and fleshed-out as the heroes. My clients sometimes accept this and let it show in their revisions — but it’s almost always an incredibly hard sale, and they fight it hard. They’re way too invested in the idea that their protagonists shouldn’t have to grow or change — the world has to change and grow for them.

I sometimes have to be a therapist of sorts to the most stubborn of these clients, and tease out the autobiographical angst that informs the victim fantasias, so they can separate that out, set it aside, and focus on craft as much as catharsis.

You’re right about an editor being a therapist. There’s a story right there!

I like this post very much. So often we are focused on the heroes and not the villains. But as writers we know that the villains are the most fun to write (at least for me).

One of my favorite villains was portrayed in Ordinary Thunderstorms by William Boyd. Not many people have read this book. I enjoyed it. The villain was very scary and very competent in his quest to destroy the hero. What made this sociopath special is the dog he adopted and later had to kill to survive. I had great trouble with that because I can’t read about innocent animals dying. I skipped ahead to avoid the dog’s murder. (The villain had been agonizing about killing the dog for pages–never once did he agonize about killing innocent people.). Once I skipped ahead, I had a surprise. He didn’t kill the dog!!! That made him a perfect villain in my mind and I tipped my hat to William Boyd.

That’s a great tribute to a writer, Joan, that you were effected in such a way. Thanks for passing that along.

#protip: Psychosexual motivations = boring.

JSB–

What a fine, dead-on accurate post–thank you very much. I truly believe that anyone applying what you say here to her/his villains would be way ahead of the game.

My villain in The Anything Goes Girl is less a person than a mindset that serves as the operating principle for my actual antagonists. As with Goering, it’s the ends justifying the means. If the outcome of exploiting a few people has the potential for bringing about “the greater good,” all is made right.

I also include an unconventional conventional criminal. He has finessed any problem of conscience by thinking of what happens to his victims as bad Karma, the roll of the dice, chance. We all die, and the people he kills have simply come to that point a little sooner. Problem solved.