James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Back when I was pounding the Off-Broadway boards I got a bit part in a production of Othello. I got to wear tights and say Shakespeare things.

Our Othello was the marvelous stage actor Earle Hyman, better known to most of you as Bill Cosby’s father on The Cosby Show. In point of fact Earle is one of the great Othellos. He is also a very nice man.

Once we were chatting backstage and I told him that someday I would love to play Iago. He said I would be perfect for it because I had such an open, honest face (this was before I went to law school). That, after all, is what makes Iago powerful. Othello calls him “My friend … honest, honest Iago.” And if the part is played right there is even a touch of sympathy for Iago at the end as he’s dragged off to be tortured to death.

This, in fact, is what set Shakespeare apart from his contemporaries. He knew how to mangle the emotions of the audience, even to the point of rendering some sympathy for the devil.

Dean Koontz wrote, “The best villains are those that evoke pity and sometimes even genuine sympathy as well as terror. Think of the pathetic aspect of the Frankenstein monster. Think of the poor werewolf, hating what he becomes in the light of the full moon, but incapable of resisting the lycanthropic tides in his own cells.”

All this to say that the best villains in fiction, theatre, and film are never one-dimensional. They are complex, often charming, and able to manipulate. The biggest mistake you can make with a villain is to make him pure evil or all crazy.

So what goes into crafting a memorable villain?

1. Give him an argument

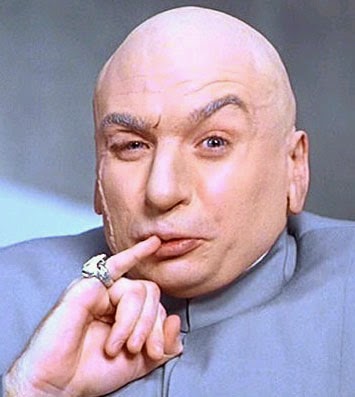

There is only one character in all storytelling who wakes up each day asking himself what fresh evil he can commit. This guy:

But other than Dr. Evil, every villain feels justified in what he is doing. When you make that clear to the reader in a way that approaches actual empathy, you will create cross-currents of emotion that deepen the fictive dream like virtually nothing else.

One of the techniques I teach in my workshops is borrowed from my courtroom days. I ask people to imagine their villain has been put on trial and is representing himself. Now comes the time for the closing argument. He has one opportunity to make his case for the jury. He has to justify his whole life. He has to appeal to the jurors’ hearts and minds or he’s doomed.

Write that speech. Do it as a free-form document, in the villain’s voice, with all the emotion you can muster. Emphasize what’s called “exculpatory evidence.” That is evidence that, if believed, would tend to exonerate a defendant. As the saying goes, give the devil his due.

Note: This does not mean you are giving approval to what the villain has done. No way. What you are getting at is his motivation. This is how to know what’s going on inside your villain’s head throughout the entire novel.

Note: This does not mean you are giving approval to what the villain has done. No way. What you are getting at is his motivation. This is how to know what’s going on inside your villain’s head throughout the entire novel.

Want to read a real-world example? See the cross-examination of Hermann Goering from the Nuremberg Trials. Here’s a clip:

I think you did not quite understand me correctly here, for I did not put it that way at all. I stated that it had struck me that Hitler had very definite views of the impotency of protest; secondly, that he was of the opinion that Germany must be freed from the dictate of Versailles. It was not only Adolf Hitler; every German, every patriotic German had the same feelings. And I, being an ardent patriot, bitterly felt the shame of the dictate of Versailles, and I allied myself with the man about whom I felt perceived most clearly the consequences of this dictate, and that probably he was the man who would find the ways and means to set it aside. All the other talk in the Party about Versailles was, pardon the expression, mere twaddle … From the beginning it was the aim of Adolf Hitler and his movement to free Germany from the oppressive fetters of Versailles, that is, not from the whole Treaty of Versailles, but from those terms which were strangling Germany’s future.

How chilling to hear a Nazi thug making a reasoned argument to justify the horrors foisted upon the world by Hitler. So much scarier than a cardboard bad guy.

So what’s your villain’s justification? Let’s hear it. Marshal the evidence. Know deeply and intimately what drives him.

2. Choices, not just backstory

It’s common and perhaps a little trite these days to give the villain a horrific backstory and leave it at that.

Or, contrarily, to leave out any backstory at all.

In truth, everyone alive or fictional has a backstory, and you need to know your villain’s. But don’t just make him a victim of abuse. Make him a victim of his own choices.

Back when virtue and character were actually taught to children in school, there was a lesson from the McGuffey Reader that went like this: “The boy who will peep into a drawer will be tempted to take something out of it; and he who will steal a penny in his youth will steal a pound in his manhood.”

The message, of course, is that we are responsible for our choices and actions, and they have consequences.

So what was the first choice your villain made that began forging his long chain of depravity? Write that scene. Give us the emotion of it. Even if you don’t use the scene in your book, knowing it will give your villain scope.

3. Attractiveness

The devil is not a cloven-hoofed, red-suited, pointy-eared demon with a pitchfork. Indeed, the Bible says Satan appears “as an angel of light.” He is the most beautiful of the heavenly host. His mode is to entice, not coerce.

The same with the best villains. They are sometimes attractive through raw, worldly power (Gordon Gekko). Intellect may be their weapon (Hannibal Lecter). Or a certain way with the opposite sex (innumerable homme and femme fatales). Hitchcock’s best villains were charming and therefore disarming. They often had wit and style. (My favorite is the widow-murdering uncle played by Joseph Cotten in Shadow of a Doubt.)

Give your villain at least one attractive feature and then see what the other characters do with it.

The strength of a thriller is directly proportional to the strength of the villain. The reader has to feel that this character has got what it takes to pull the wool over the eyes of the many. And if you create a touch of empathy as well, you’ll have your storytelling hooks deeply embedded in the readers’ hearts. They’ll thank you for that by buying your next book.

What’s your approach to villain writing?