The rhetorical triangle is a concept that rhetoricians developed from the Greek philosopher Aristotle’s idea that effective persuasive arguments contain three essential elements: logos, ethos, and pathos.

The rhetorical triangle is a concept that rhetoricians developed from the Greek philosopher Aristotle’s idea that effective persuasive arguments contain three essential elements: logos, ethos, and pathos.

Its purpose? To inform, persuade, entertain — whatever the author wants the audience to believe, know, feel, or do.

All forms of communication use the tools of rhetoric to some degree. Though the rhetorical triangle sounds like it’s geared toward nonfiction writing, novelists can use it as a literary devise.

Logos

Logos establish reliability. We want readers to believe our main character. By using factual information and logic, we’re building connections in the reader’s mind.

An example of logos:

Facts: Mr. Duke owns a tea shop. He talks about his passion for tea.

Logic: Mr. Duke has liquid in a teacup. Because of his passion for tea and the fact that he owns the tea shop…

Conclusion: The liquid in his teacup must be tea.

Are we jumping to conclusions too soon? Maybe. Is any other information available? Does Mr. Duke slur his words? Then maybe there’s alcohol in that teacup. Or he has a medical issue. Given the social constructs and the available information, the reader concludes he’s drinking tea.

Logos do get more complicated, but it always retains these basic parts. And we, as writers, need to recognize the order in which readers draw conclusions. By doing so, we can manipulate the narrative to suit our needs.

Ethos

Ethos boils down to one burning question: Can the reader trust you? If you write nonfiction, citations from reliable sources help build trust. Or you consistently share reliable information, leading your audience to trust what you say is true.

In fiction, ethos may simmer in the background, invisible to the reader. The MC shows the audience they are trustworthy through actions, reactions, and the choices they make.

Pathos

Pathos is the emotional pull. Authors use pathos to evoke certain feelings from the reader. For our purposes, pathos is a literary device rather than a rhetorical one. Pathos establish tone or mood or make the reader feel sympathetic toward a character. By using pathos, we can trigger readers to feel happy, sad, angry, passionate, inspired, or miserable through word choices and plot development.

Pathos is a Greek word meaning “suffering” that has long been used to relay feelings of sadness or strong emotion. Adopted into the English language in the 16th century to describe a quality that stirs emotions, it’s often produced by real-life tragedy or moving language.

Pathos became the foundation for many other English words.

- Empathy — the ability to understand and feel the emotions of others

- Pathology — the study of disease, which can cause suffering

- Pathetic — something that causes others to feel pity

- Sympathy — the shared feeling of sadness

- Sociopath — causing harm to society

- Psychopath — suffering in the mind

Pathos is the basis for the art of persuasion.

Ever watch commercials for pet adoptions? The sad puppy dog eyes plead for a forever home. They rip your heart out, right? That’s pathos at work.

Most readers want to feel something when they crack open a novel. An emotion pull connects the reader to the characters, immerses them in story, and keeps them flipping pages. Pathos also explains why some stories are unforgettable — because we lived it with the characters! We feared for their safety. We cried over their heartbreaks. We cheered over their victories. The characters became our friends, maybe even family, and we miss them as soon as we close the cover.

Since it’s easier to spot pathos in music lyrics…

God Bless the USA by Lee Greenwood: “And I won’t forget the men who died who gave that right to me…”

Nothing Compares 2 U by Sinead O’Connor: “It’s been so lonely without you here, like a bird without a song.” Or “All the flowers that you planted in the backyard, Mama, all died when you left.”

To start your week off on the right foot, I’ll embed Happy by Pharrell Williams. An obvious pathos is: “Clap along if you feel like happiness is the truth.”

Anyone who can sit still during this song might be dead inside. 😉

Did you spot other pathos in the video? Have you heard of the rhetorical triangle? What other ways might we use logos, ethos, and pathos?

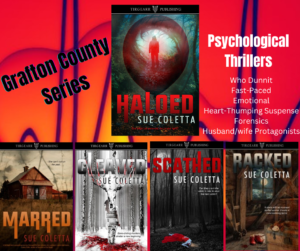

When I bought back my rights to

When I bought back my rights to

As I tell this story, think back over your life. We’ve all gone through hard times, some worse than others. Humor me, and if you’re struggling with story structure, you’ll at least begin to grasp it by the time you’ve read this post. That’s my hope, anyway.

As I tell this story, think back over your life. We’ve all gone through hard times, some worse than others. Humor me, and if you’re struggling with story structure, you’ll at least begin to grasp it by the time you’ve read this post. That’s my hope, anyway.

With the fate of the Natural World at stake, can a cat burglar, warrior, and Medicine Man stop trophy hunters before it’s too late?

With the fate of the Natural World at stake, can a cat burglar, warrior, and Medicine Man stop trophy hunters before it’s too late? Many new writers struggle with how to emphasize words in fiction. It’s tempting to stick a word in ALL CAPS.

Many new writers struggle with how to emphasize words in fiction. It’s tempting to stick a word in ALL CAPS. Ever wonder why pumpkin spice is so popular? The fascinating part is not only does it taste amazing, but many are obsessed with how it makes them feel on an emotional level.

Ever wonder why pumpkin spice is so popular? The fascinating part is not only does it taste amazing, but many are obsessed with how it makes them feel on an emotional level.