Place is character. And all writing is regional. — John Dufresne.

By PJ Parrish

Man, do I need a vacation.

Like most of you, I haven’t been much of anywhere these past 18 months, and my itch to travel has gone from wanderlust to wander-horny. I love to go places I’ve never been before — anywhere! Be it the wooded path in Michigan I’ve never jogged down before to the Camargue in southern France.

We were scheduled to go to Provence last fall but that was cancelled. So I’ve had to content myself with binging on Escape To The Chateau and Stanley Tucci: Searching For Italy. And I’ve read a lot of books.

Nina George took me to favorite old haunts and beyond in The Little Paris Bookshop. Georges Simenon took me to a Normandy fishing village in Maigret et la Vielle Dame. Stuart Neville took me to northern Ireland in The Ghosts of Belfast. And I have just embarked to Newfoundland, piloted by Jim DeFede who recounts the true story of the villagers of Gander who took in 7,000 passengers stranded in the wake of 9/11 in his book The Day The World Came To Town.

These journeys and many others have helped keep me sane. The books have also gotten me to thinking about what makes for a great location in a novel. I’m a sucker for sense of place. I can almost forgive poor characterizations or lazy plotting if the location is well rendered.

I think sense of place is often neglected by writers who are just finding their feet. Maybe they believe that like description, it slogs down the plot. I believe, however, that if you don’t ground your reader in a sense of place, the characters never truly come alive.

As John Defresne says in his splendid writing fiction book The Lie That Tells The Truth:

“Place connects characters to a collective and personal past, and so place is the emotional center of story. And by place, I don’t simply mean location. A location is a dot on the map, a set of coordinates. Place is location with narrative, with memory and imagination, with history. We transform a location into a place by telling its stories.

The chapter that passage comes from is titled: “You Can’t Do Anything If You’re Nowhere.” No place, no plot, nowhere man.

So, let’s try to get practical here. What can I tell you that might help you as a fiction writer, get a better sense of your place? That’s tough. I can only go by my own experience writing and reading. Place is often my jumping off point. In my Louis Kincaid series, I move him between southwest Florida and Michigan. But within that macro, I try to find specific mini-locations that speak me and help me put a frame around my character. These mini-locations have been: The Everglades, an abandoned insane asylum, a remote island in the Gulf, the vast emptiness of the Sleeping Bear sand dunes, and the rugged loneliness of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, with its abandoned copper mines. I have a thing for abandoned places.

For our stand-alone A Killing Song, Paris was the macro-location. The mini-location was the creepy network of catacombs beneath the city. We also took our readers to the Arab enclave called La Goutte d’Or, the strange park Buttes-Chamont, a dive bar tucked behind the Pantheon called El Melocoton.

We didn’t take our readers to the Eiffel Tower, the Tuileries gardens, or Cafe Deux Magots.

Why? Here is the best piece of advice I can give you regarding creating a sense of place: Don’t go with the obvious. Steer clear of all clichés. The more well-known and iconic your setting is, the harder you have to work to find within it the telling details that make it come alive in your reader’s imagination. Make your setting FRESH.

Writing about New York City? Take me places I haven’t seen in TV. Writing about Hong Kong? Give me the smells and sounds that movies cannot. Miami? Stay away from South Beach and Little Havana. San Francisco? No Wharf, Alcatraz, cable cars and go light on the fog. Stay away from tired place memes that are over-used so much they lose all emotional impact.

Your postcards from the edge must have an edge.

Okay, enough beating you over the head about cliches. What else can I offer?

Write what you know. This does not mean you have to visit all your locales. It helps. Boy, does it help. I’ve got a very good working knowledge of Paris but I had never been to La Goutte D’Or. I traveled every inch of its streets via Google Street View. But you can create a great location if you do your research the people, language and culture. Remember: What may be colorful and exotic to you as a writer is just normal life to the people who live there.

Compare and contrast. If your character is a stranger in strange land, use his experiences and memories of his normal world and contrast it with what he is observing. I did this often in The Killing Song with my American Matt, a Floridian who had never been abroad. I used his naivete, frustration, and fears to create the same feelings for readers.

What is the scene about? You need to pin this down before you begin piling in details of location. Don’t just say to yourself: I’m going to set a scene at Muir Woods because I was there once and the old trees were cool. Figure out what needs to happen to your character FIRST and then make the setting enhance the plot and the mood. Watch this great scene in Vertigo where Kim Novak wanders among the ancient trees, says she’s thinking about “All the people who have lived and died while the trees went on living.” The haunting setting reflects her confused mood.

Use All Your Senses!

This is a tenet of all good description but especially for creating settings. The smells of an exotic street bazaar. The sounds of shrieking wild parrots in the palm trees of Miami Beach. The fusty smell of cold earth in a graveyard. The simple sense of feel became critical in our book The Killing Song. Near the climax, Matt is forced to crawl through the narrow tunnels of the catacombs. He is claustrophobic, due to a childhood accident, and he’s terrified.

Shivering, I got up and moved on. I was dismayed to see the passageway starting to narrow again, and before long I was forced to my knees. The passageway continued to shrink until I was flat on my belly, looking into a hole about the size of a large heating vent.

I wiggled forward and twisted my body so I could shine the flashlight into the hole.

Bones. As far as I could see.

A brown, jagged carpet of them in a passageway no larger than a coffin.

I closed my eyes, fighting back nausea. I pulled in a deep breath and slithered forward into the hole. Eyes closed, I started a soldier’s crawl across the bones. I could feel the sharp edges rip at the sleeves of my jacket. I could hear the dry crunch, like beetles being crushed, as the bones broke under the weight of my body.

Don’t Overdo It. It’s easy, during research, to fall hopelessly in love with your setting. You must know what to leave out. Dan Brown, who some might say never met a location he didn’t love, puts it this way: “Readers are interested in your characters and plot, so information about your world is best conveyed through a character’s sensory experience or through action.”

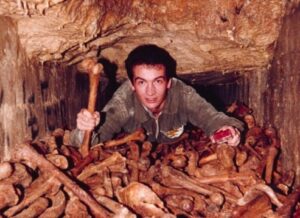

Use Visual Aids. I did this often with our Louis books. I made many treks into the Everglades or locations around Ft. Myers and took hundreds of photos that found their way onto an inspiration wall as I wrote. I found this photo of a “cataphile” while researching the Paris catacombs and it inspired the scene above with Matt:

I also keep old fashioned fold-up physical maps handy, which oddly give me a better sense of where I am in a book than any Google Map ever could. I often created my own maps of places I had made up, like the grounds of the abandoned insane asylum.

Imagine Your Story Is a Movie

Some of you have actually screenwriting experience. I do not. But I often can visualize my scenes as movies. I can see in my mind an establishing setting shot, long, medium or close up. If you can visualize this, you can really get your reader grounded in a reality of location.

One last example before I leave. I also re-read To Kill A Mockingbird this past year. I had to go back and find this for you, but it still strikes me as one of the best opening descriptions of place that I can remember:

Maycomb was an old town, but it was a tired old town when I first knew it. In rainy weather the streets turned to red slop, grass grew on the sidewalks, the courthouse sagged in the square. Somehow it was hotter then . . . bony mules hitched to Hoover carts flicked flies in the sweltering shade of the live oaks on the square. Men’s stiff collars wilted by nine in the morning. Ladies bathed before noon, after their three-o’clock naps, and by nightfall were like soft teacakes with frostings of sweat and sweet talcum.

This is, of course, seen through Scout’s point of view. It not only establishes Maycomb as a tired place, but it is written as a recollection of Scout as an adult. We get a sense of poverty, idleness, and oppression that comes to underscore the story’s themes.

I’m off to research things to see near St. Remy de Provence. Yes, we are planning to go this fall. So I’ll let John Defresne have the last word:

“You wouldn’t be here if you didn’t want to write, so let’s write. We’ll chat later. Get out your pen and paper or fire up the computer. Pour yourself a coffee. Unplug the phone. Once you start, you can’t stop. Give yourself a half hour. Relax. Don’t think too much. You’re starting a journey, and you don’t know where you’re going. But you do know you’re going someplace you haven’t been before.”

My apologies to the brave writer who submitted this first page for critique. I meant to do it sooner, but I’ve had an insanely busy October.

My apologies to the brave writer who submitted this first page for critique. I meant to do it sooner, but I’ve had an insanely busy October.

Recently one of our regulars, RLM Cooper,

Recently one of our regulars, RLM Cooper,

A controversy over an award-winning female thriller author has broken out in Europe. That’s because the female thriller author doesn’t exist. “She” is really three men who have been writing under the pseudonym Carmen Mola. When one of their novels won a million-euro prize, the trio

A controversy over an award-winning female thriller author has broken out in Europe. That’s because the female thriller author doesn’t exist. “She” is really three men who have been writing under the pseudonym Carmen Mola. When one of their novels won a million-euro prize, the trio