by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Here is another in our series of first page critiques. This one presents an important craft issue which I’ll discuss on the flip side.

Here is another in our series of first page critiques. This one presents an important craft issue which I’ll discuss on the flip side.

Crossing the Line

He stood with his back to the doors leading to the balcony overlooking Lake Waco. His eyes remained focused on the 9mm Glock in the hand of Deputy U. S. Marshal Seth Barkley.

“What do we do now?” asked the blond-haired man. “Is this the part where you handcuff me and cart me off to jail?”

“You’re not ever going to see the inside of a jail,” Barkley responded.

“So you’re my judge and jury?”

“I’m the closest you’re going to get.”

“You can’t shoot an unarmed man.”

“You’re unarmed?” Barkley smiled. “What’s that in your hand?”

The man glanced at the dagger he was holding. “You know the old line about bringing a knife to a gun fight. You would shoot me before I got within six feet of you.”

“That’s a better deal than the one you offered your victims, but you’re right. Let’s make this fair.” The marshal reached behind his back and pulled his backup pistol from the waist of his jeans. He stooped down, laid it on the floor, and then kicked it with his foot toward the man.

“Pick it up,” Barkley said.

“No, you’ll shoot as soon as my hand touches the weapon.”

“I’ll shoot you either way. At least this way you stand a chance of living.”

Sweat poured down the man’s face as he looked from Barkley to the gun laying on the floor in front of him.

“You can’t do this, damn it, you’re a United States Marshal.”

Barkley unclipped the badge from his belt and tossed it to the side. The clink of the metal on the tile floor reverberated throughout the room. He holstered his weapon.

“Feel better now?” he asked, his eyes never leaving the eyes of his opponent.

“I didn’t do anything to those women they didn’t deserve.”

“So, you’re telling me you’re innocent in all of this because the women you stalked, tortured, and murdered asked for it?” Barkley said. The man went silent and glared into Barkley’s eyes.

The time was upon him, and his darkest fear realized. Seth Barkley was stepping over that imaginary line that would make him like his old man. His life would never be the same after crossing over from good to evil.

Barkley pulled his weapon and slowly eased the trigger. “This is for Kaitlyn,” Barkley said. He was now a vigilante, no going back.

***

JSB: The main point I want to make is about this piece deals with “on the nose” dialogue. That’s an old Hollywood term which means dialogue that is direct and predictable. Predictability is what makes reading boring. So learning to write “from the side of the nose” will immediately increase interest and readability.

Another problem that often shows up in dialogue at the beginning of a novel is that it overstuffs exposition. The result is that the reader gets the impression it’s the author talking, feeding us information, and not the characters talking to each other. You need to ask these questions of all your dialogue:

- Would the character really say that, in that way? If not, rewrite it, and don’t be afraid to cut.

- Is the character telling the other character things they both already know? If so, you should err on the side of cutting it. (You’ll sometimes see this when characters use each others’ names: “Hello, Frank.” “Nice day, isn’t it, Audrey?”)

The dialogue in this piece is back and forth, direct response, on-the-nose, and states things for the benefit of the reader. Remember my axiom: act first, explain later. And since dialogue is a compression and extension of action, that axiom applies here.

Here is a quick rewrite of the first few lines of dialogue:

“What do we do now?” asked the blond-haired man.

“You’re not going to see the inside of a jail,” Barkley said.

The man glanced at the dagger he was holding.

What’s left unsaid, what’s “between the lines,” is in the reader’s head now, and creating interest.

Here’s another way:

“What do we do now?” asked the blond-haired man.

“You’re not going to see the inside of a jail,” Barkley said.

“Shooting an unarmed man?”

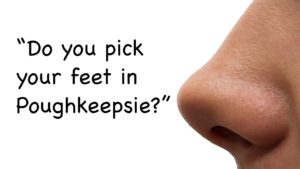

“Do you pick your feet in Poughkeepsie?”

What?

Some of you will recognize that last line of dialogue from the classic cop movie The French Connection. Based on the real-life NY cop Eddie “Popeye” Egan, this totally off-the-nose line was used by Egan (and by Gene Hackman as Popeye Doyle in the movie) to completely throw off a suspect being interrogated. The suspect would get so rattled by this oddball question from the “bad cop” that he’d give up something to the “good cop.”

It works here because we, the audience, are also going, “What? What’d he just say? Why? Why is he saying that?”

Which means you have their interest!

Now, of course I’m not saying our writer should use that exact line. I am merely pointing out that “side-of-the-nose” dialogue works wonders. By side-of-the-nose I mean something that is not a direct response, and indeed at first hearing sounds like it doesn’t make sense!

Write, try it. Make up your own oddball line of dialogue. Even be random about it, and justify the line later!

Writing from the side of the nose is also helpful for avoiding exposition-heavy dialogue, like this: “You can’t do this, damn it, you’re a United States Marshal.”

They both know he’s a U.S. Marshal. You told the readers this in the first paragraph. Cut that line of dialogue and see how the action moves forward, faster.

Here’s another line you can cut:

“So, you’re telling me you’re innocent in all of this because the women you stalked, tortured, and murdered asked for it?” Barkley said. The man went silent and glared into Barkley’s eyes.

But, you protest, that explains this entire scene! To which I respond, act first, explain later. We don’t need to know why a U.S. Marshall is executing this guy at this moment in time. Leave a mystery!

Which brings us to the last two paragraphs, which are heavy with telling us what Barkley is becoming. As wth all exposition, ask: do we need to know that now? Here’s a shock: Almost always the answer will be no.

What if the scene ended this way:

“I didn’t do anything to those women they didn’t deserve.”

Barkley pulled his weapon. “This is for Kaitlyn,” he said.

What? End it there? Why not? The reader will be compelled to turn the page. And when he or she does, make them wait to find out what just happened. You could shift to another POV, or you could show us Barkley doing something, and through his actions we start to see what he’s becoming …

Bottom line: Check your dialogue and narrative for on-the-nose writing. Cut it. Surprise us with dialogue and details that are odd, surprising, mysterious, unpredictable.

Three other notes:

The first couple of lines give the impression we are in the “he” POV. But the scene ends in Barkley’s POV. Be strongly in Barkley’s head from the outset.

Barkley responded is redundant. Use said.

Barkley pulled his weapon and slowly eased the trigger. (You mean squeezed the trigger).

Okay, TKZers, your turn. I’m traveling today and probably won’t be able to comment. So take it away and help our brave writer.

Kicked it (with his foot is superfluous)…but then superfluous is writerly

I was confused in the first sentence. (The door, the balcony, Lake Waco back to what?) It could be I just need more coffee. I had trouble picturing which side of the door “he” was standing on.

I liked the sound of the badge hitting the tile. Adding more sensory detail would help ground the setting and also break up the dialogue.

One of my favorite “side of the nose” bits of dialogue was in the Racen Boys by Stiefvater. Bunch of rowdy boys in a pizza joint, hitting on the girl. One of the boys manages to take her hand. She exclaims, “Your hands are so cold!” He replies, “I’ve been dead for seven years.”

It’s the absolute truth, but in the context of the scene, it feels like a big joke. The reader pays no attention to it until later.

Raven Boys*. Hazards of typing on a little screen.

I liked the immediate tension in the opening, but I felt misled into thinking we were in the blond man’s POV right off the bat. I thought so right up to the line about Barkley’s eyes never leaving the eyes of his opponent, then I realized we were in Barkley’s POV. This, however, is easily fixed.

I also agree with Jim Bell about the last line. “‘This is for Kaitlyn,’ he said” is a much better place to end it.

Also, the “side of the nose” dialogue (a great phrase) is needed to replace the more direct dialogue.

Apart from these minor changes, I liked this piece very much.

P.D. James talks about getting to know a character before you have something bad happen. As it stands, I, the reader, have no reason to care about either man, no hint of who is the protagonist and who is the antagonist. Setting up the critical moment can make it even more intense Jim Thompson was very good at making bad guys into heroes. (The Killer Inside). In this case, maybe a chase through the woods showing some of the motivation for each character is one way to go.

Then, on the balcony, when the wrong thing happens, you have a story.

I’m a sucker for these types of stories so keep it up!

A few things:

1) This feels like prologue. Is the next chapter going to be 5 years later or 1 year earlier or some other time? Are we going to be meeting our erstwhile hero in his new career as a vigilante, a disgraced Marshal, a burned-out bartender in the Keys who discovers he shot the wrong man? If so, this can be a lot shorter.

2) Trust your audience. This is a job for inference. There’s no need to describe every interim motion in an action:

“The marshal reached behind his back and pulled his backup pistol from the waist of his jeans. He stooped down, laid it on the floor, and then kicked it with his foot toward the man.” ——————-> “Barley dropped his backup piece and kicked it toward him.”

Every physical action has to advance the action or tension. Leave the rest for inference.

3) The eyes have it. Of all things, “eyes” is one of the words you need to do a global search for and delete it whenever possible. It’s almost never needed, is clutter, and can add the unintended humor of free-moving body parts if not careful. I had eyes crawling over my main character’s tattoos in one unfortunate passage. Now that would be creepy. You have eyes doing all sorts of things here.

4) Your first sentence reads more like a stage direction telling the director where to place the actor. Everything must serve the action. Inference is key.

———————————————-

The three-state hunt for the blond man ended when Barkley trapped him against the balcony doors at a Lake Waco hotel.

“You’re going to shoot an unarmed man?”

Barkley dropped his backup piece and kicked it toward him. “There, now we’re even.”

“You’re still a US Marshal.”

The sound of his badge hitting the tile floor was louder than he expected. The sound of a broken oath.

“I didn’t do anything to those women they didn’t deserve.”

Barkley pulled his weapon. “This is for Kaitlyn.”

——————————————————

Less than 25% of the words with the gist of the action contained. And no eyes are mentioned doing anything. (I still don’t like starting two sentences with “Barkley.”)

This was one of the hardest lessons for me to learn. And I still do the name thing waaaaaay too often.

Ask yourself if you are moving or describing. Trust the reader to fill in the blanks. I’m a big fan of flash fiction. There is no space for:

“Mary picked up the spoon and began to serve the potatoes from the bowl.”

equals

“Mary served the potatoes.”

Unless the spoon or the bowl are plot-critical, you can infer Mary didn’t scoop them raw out of the garden with her bare hands (unless she did and that was key to the plot.)

A noted flash fiction writer said about inference that when she put her characters in church, she trusted the reader to assume they have dressed appropriately because she never ever described a piece of clothing unless it (or the lack thereof) was critical to the plot.

You’ve totally got this – good work: Terri

As you said, the writing is too on the nose. More than that, for me, is there isn’t much if any distinction in the voices. Take away the gun and they could be discussing the weather, or some fairly innocuous subject, their voices flat and even.

What if the first thing the suspect said was, “I want a lawyer,” blurting it out as soon as he realizes he’s been caught. All he’s thinking about is himself. “What happens now” is making a game of it, and while they do that all the time on TV, it never feels real.

The marshal looks at him, cocking his head to one side, gives a small smile and says, “Nah.”

“I’ve got rights.” the suspect says, his voice rising an octave. “I’m not saying anything ’til I talk to a lawyer!”

The marshal shakes his head, says something like, “You’ve also got the right to remain silent, but I don’t think that’ll be a problem.” He glances around to make sure there are no witnesses, then raises his pistol, the slightest tremor revealing his inner doubt. The suspect starts to protest.

“Wait, I have …”

His protest is cut off by the sound of three shots reverberating in the small room (hotel room? Kinda sounds like it) and the thud of the body spinning against the wall and crashing to the floor.

THEN the marshal closes his eyes and says, “That was for you, Kaitlyn.” Actually I don’t like him saying the name out loud, he knows who it is, he’s only naming her for the reader.

Maybe that’s just me. But it sure seems like a case where less would be more.

Thank you everyone for reading the first page of my book. You all know how difficult, but important it is to convey a storyline in so few words. The first page of Crossing The Line is taken from the last ninety percent of the book and the relationship

of all the players is explained in the first chapter. The last chapter answers some shocking questions as well as asking some.

And you are correct, Mr. Bell. It is “squeezed” the trigger. That was a rookie mistake on my part.

Again, thank you and Happy Mother’s Day to those of you who are mothers.

Anonymous Author

I have learned so from your comments and appreciate the time you have taken from Mother’s Day to help make my book even better.?

Best of luck. Keep writing.

I agree 100% that the dialogue is too on the nose, and I was a tad confused about who the blonde man was at first.

A good way to practice dialogue is to do that old standby exercise of secretly writing down overheard conversations. (Not recording them digitally!) You soon learn that people almost never talk to a direct conclusion. In two or three lines, they’re off on tangents. Sometimes they come back to the subject, sometimes they never do.

But all the dialogue should be relevant in some way, if only to illustrate the character more deeply. Notice how–when you’re in conversation–that we very often answer questions with questions. It’s a great way to move the story ahead in fiction.

Great start!

I agree with every one of Brother Bell’s points. I have one continuity issue. In the first paragraph, “he” is staring at the Glock in the marshal’s hand, then in the last paragraph, the marshal pulls his weapon. Can it be both ways? (Also, double check the caliber. A distant voice in my head tells me that the marshals carry .40 caliber, but there’ve been so many changes in recent years, I could be wrong.) In my experience, marshals carry their badges in some sort of leather backed wallet. Would it still clink when it hit the floor, or would it, well, thock?

My larger issue with this piece is that I feel like I’ve seen every beat before, even down to the drop gun.

I hope all of the moms had a wonderful Mother’s Day. I have a couple of suggestions for the author that I hope will be helpful.

♥ One quick suggestion concerns using “responded” as a dialogue tag. I like “replied” better, because it’s only two syllables and doesn’t stand out as much.

♥ The opening line is: “He stood with his back to the doors leading to the balcony overlooking Lake Waco.” Shortly after this sentence, a man is identified by his hair color: “What do we do now?” asked the blond-haired man.

I recommend beginning with a named character. If Barkley is the protagonist, I’d begin with a powerful sentence about him. I’d spend some time on crafting a great opening line. Don’t let working on an opening line halt your writing progress, though. You can be mulling over your opening line while you’re working on the rest of the book!

♥ Some writers devote too much time describing the setting, but I think this opening needs to ground the reader in the setting a little bit more.

♥ Mr. Bell and some of the other writers mentioned “on the nose” dialogue. I happened to write a post about this on my blog awhile back that might be helpful. (https://writesomethingyoulove.com/2017/03/21/hold-the-on-the-nose-dialogue/) It’s definitely better to lead with a little more mystery.

Btw, I like the title of this story. Have a great day, brave writer, and carry on! ♪♫♪♫♪♫

The page I submitted was an Prologue to my completed ms which was an afterthought and which I will likely omit after the feedback received from TKZ.

The first chapter answers the questions you all have graciously asked. Mr. Gilstrap, the glock Barkley is holding is based on interviews with my local Marshal Service and a close friend is who a deputy marshal and allows me to train at his ranch. I carry a Glock 19, Gen 4 and use 9mm Luger ammunition. I erred in the Prologue on which Glock Barkley carries. Elsewhere in the ms he uses a .40 Glock. Thank you for pointing that out.

The second piece Barkley kicks toward the antagonist with his boot is his back-up ACP. I am sorry if there was confusion. I still have a lot to learn and appreciate what TKZ teaches me.

I read every critique and every blog post. You all are to be commended for the time you give to help those of us who are newbies.

Also, Mr. Gilstrap, aside from the Prologue, I think you will enjoy and be surprised by the story of Stalking The Stalker. At least I hope so. I tweeted you once about the frustration I felt after my first rejection by an agent, and you tweeted back how long it took you to find an agent. I found so much comfort in that,

Thank you very much for your input.

Just when I thought it couldn’t get any worse I read the first line of my response and noticed the error, “an Prologue ” and have only the excuse I haven’t slept in days.

Sorry. A member of TKZ once wrote to an anonymous author that they must not give a shit if they didn’t take the time to check for errors. I assure you I do give a damn.

Again, thank you all for what you do for us.