In story terms, a villain is a person, entity, or force who is cruel, evil, or malicious enough to wish the protagonist harm. Rather than simply blocking a goal or interfering with the hero’s plan, a villain causes suffering, making it vital for them to be conquered by the protagonist. Clarice must find and defeat Buffalo Bill if she wants to rise above her past and become a great FBI agent (The Silence of the Lambs); Chief Brody must kill the man-eating shark to preserve his town (Jaws).

In story terms, a villain is a person, entity, or force who is cruel, evil, or malicious enough to wish the protagonist harm. Rather than simply blocking a goal or interfering with the hero’s plan, a villain causes suffering, making it vital for them to be conquered by the protagonist. Clarice must find and defeat Buffalo Bill if she wants to rise above her past and become a great FBI agent (The Silence of the Lambs); Chief Brody must kill the man-eating shark to preserve his town (Jaws).

Regardless of the form your villain takes, there are certain qualities that will make them formidable and credible—qualities and connections they share with the protagonist. Let’s explore these qualifications through a case study of Dr. Lawrence Myrick, played by Gene Hackman in the movie Extreme Measures.

VILLAINS, LIKE HEROES, LIVE BY A MORAL CODE

It’s been said that the best villains don’t know they’re villains; they think they’re the hero of the story. And this is true because a well-crafted baddie has his own moral code. Compared to the protagonist’s, it’s twisted and corrupt, but it still provides guardrails that guide him through the story.

Dr. Myrick is a renowned and brilliant neurosurgeon who has dedicated his life’s work to curing paralysis. It’s a noble cause that he believes in more than anything—not so much for himself but for all the paralyzed people in the world. This cause is so important that when he develops a treatment, he can’t wait decades for it to crawl through the testing process and eventually be approved. So he bypasses the animal testing phase and goes right to human trials. It’s kind of hard to find healthy subjects who are willing to take such a risk, so he kidnaps homeless people and confines them to his secret medical facility, then severs their spinal cords so he can test his treatment on them.

To the rest of the world, this is unconscionable. But to Myrick, the end justifies the means. He’s perfectly okay stealing people, taking away their freedom and mobility, and subjecting them to countless medical cruelties. And if they reach a point of no longer being useful, he’s fine doing away with them because they’re people no one will miss. He actually views them as heroes, sacrificing themselves for the greater good. His morals are deranged, but they’re absolute, guiding his choices and actions. And when you know his code, while you don’t agree with it, you at least understand what’s driving him, and his actions make sense.

When you’re planning your villain, explore their beliefs about right and wrong. Figure out their worldview and ideals. Specifically, see how the villain’s beliefs differ from the protagonist’s. This will show you the framework the villain is willing to work within, steer the conflict they generate, and provide a stark contrast to the hero.

THEY HAVE A STORY GOAL, TOO

Like the hero, the villain has an overall objective, and they’re willing to do anything within their moral code to achieve it. When their goal is diametrically opposed to the hero’s, the two become enemies in a situation where only one can succeed.

Like the hero, the villain has an overall objective, and they’re willing to do anything within their moral code to achieve it. When their goal is diametrically opposed to the hero’s, the two become enemies in a situation where only one can succeed.

We know Myrick’s goal: to cure paralysis. And things are progressing nicely until an ER doctor in his hospital discovers homeless patients disappearing from the facility. Dr. Lathan starts nosing around, and when he realizes someone is up to no good, it becomes his mission to stop them. So the two are pitted against each other. If one succeeds, the other must fail. To quote Highlander: there can only be one.

As the author who has spirited the villain out of your own (dare we say twisted?) imagination, you need to know their goal. It should be as clear-cut and obvious as the hero’s objective. Does it put them in opposition to the protagonist? Ideally, both characters’ goals should block each other from getting what they want and need.

VILLAINS ARE WELL-ROUNDED

Because villains are typically evil, it’s easy to fill them up with flaws and forget the positive traits. But good guys aren’t all good and bad guys aren’t all bad, and characters written this way have as much substance as the flimsy cardboard they’re made of. Myrick is cruel, unfeeling, and devious. But he’s also intelligent, generous, and absolutely dedicated to curing a devastating malady that afflicts the lives of many.

Positive traits add authenticity for the villain while making them intimidating and harder to defeat. An added bonus is when their strength counters the hero’s.

The villain of Watership Down is General Woundwort, a nasty rabbit whose positive attributes are brute strength and sheer force of will, making him more man than animal. In contrast, hero Hazel embodies what it means to be a rabbit. He’s swift and clever. He knows who he is and embraces what makes him him. In the end, Hazel and his rabbits overcome a seemingly undefeatable enemy by being true to their nature.

When your villain is conceived and begins to grow in the amniotic fluid of your imagination, be sure to give him some positive traits along with the negative ones. Not only will you make him an enemy worthy of your hero, he’ll also be one readers will remember.

THEY HAVE A BACKSTORY (AND YOU KNOW WHAT IT IS)

Authors know how important it is to dig into their protagonist’s backstory and have a strong grasp of how it has impacted that character. Yet one of the biggest mistakes we make with villains is not giving them their own origin story. A character who is evil with no real reason behind their actions or motivations isn’t realistic, making them stereotypical and a bit…meh.

To avoid this trap, know your villain’s beginnings. Why are they the way they are? What trauma, genetics, or negative influencers have molded them into their current state? Why are they pursuing their goal—what basic human need is lacking that achieving the goal will satisfy? The planning and research for this kind of character is significant, but it will pay off in the form of a memorable and one-of-a-kind villain who will give your hero a run for his money and intrigue readers.

THEY SHARE A CONNECTION WITH THE PROTAGONIST

In real life, we have many adversaries. Some of them are distant—the offensive driver on the highway or that self-serving, flip-flopping politician you foolishly voted for. Those adversaries can create problems for us, but the ones that do the most damage—the ones we find hardest to confront—are those we share a connection with. Parents, siblings, exes, neighbors we see every day, competitors we both admire and envy, people we don’t like who are similar to us in some way…conflicts with these people are complicated because of the emotions they stir up.

The same is true for our protagonists. The most meaningful clashes will be with the people they know. Use this to your advantage. Bring the villain in close and make things personal by engineering a connection between the two characters. Here are a few options for you to work with.

- Give Them a Shared History. The more history the two have, the more emotion will be involved. Guilt, rage, grief, fear, jealousy, regret, desire—strong feelings like these will add sparks to their interactions. They’ll cloud the protagonist’s judgment and increase the chances their villain will gain an edge.

- Make Them Reflections of Each Other. What happens when the protagonist sees him or herself in the villain? A seed of empathy forms. The hero feels a connection with the person they have to destroy, which complicates things immensely. Personality traits, flaws, vulnerabilities, wounding events, needs and desires—all of these (and more) can be used to forge a bond that will add complexity and depth to this important relationship.

- Give Them a Shared Goal. When your hero and your villain are pursuing the same objective, it accomplishes a number of good things. First, it ensures that only one of them can be the victor, pitting them against each other. But they’re also more likely to understand one another. They’ll have different reasons and methods of chasing the dream, but the shared goal can create an emotional connection.

As you can see, a lot goes into creating an enemy that is realistic, complete, and worthy of holding the title of villain in your story. When you’re drawing this character, give them the same thought and effort you’d put into your hero, and you’ll end up with a villain that will enhance your story, intrigue readers, and give the hero a run for their money.

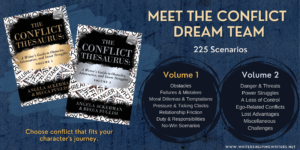

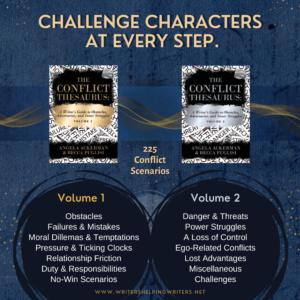

Want to take your conflict further? The Conflict Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Obstacles, Adversaries, and Inner Struggles (Volume 1 & Volume 2) explores a whopping 225 conflict scenarios that force your character to navigate relationship issues, power struggles, lost advantages, dangers and threats, moral dilemmas, failures and mistakes, and much more!

Becca Puglisi is an international speaker, writing coach, and bestselling author of The Emotion Thesaurus and other resources for writers. Her books have sold over 900,000 copies and are available in multiple languages, are sourced by US universities, and are used by novelists, screenwriters, editors, and psychologists around the world. She is passionate about learning and sharing her knowledge with others through her Writers Helping Writers blog and via One Stop For Writers—a powerhouse online resource for authors that’s home to the Character Builder and Storyteller’s Roadmap tools.

Becca Puglisi is an international speaker, writing coach, and bestselling author of The Emotion Thesaurus and other resources for writers. Her books have sold over 900,000 copies and are available in multiple languages, are sourced by US universities, and are used by novelists, screenwriters, editors, and psychologists around the world. She is passionate about learning and sharing her knowledge with others through her Writers Helping Writers blog and via One Stop For Writers—a powerhouse online resource for authors that’s home to the Character Builder and Storyteller’s Roadmap tools.

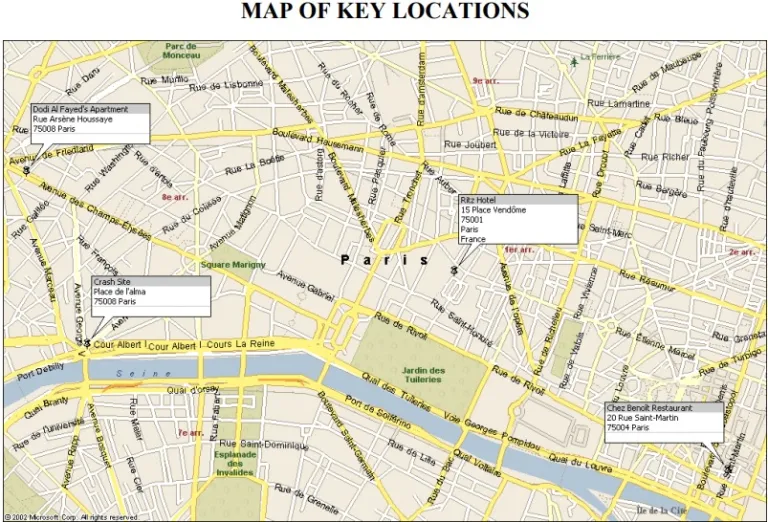

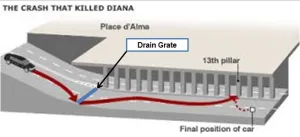

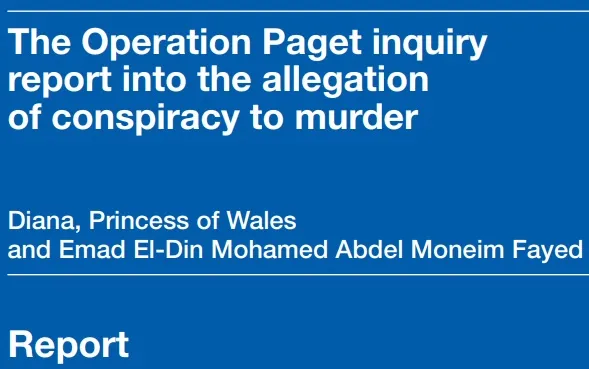

Circumstances surrounding Diana’s death are exhaustively investigated. Everyone knows basic facts that Diana and her new boyfriend, Dodi al-Fayed, were leaving a Paris hotel for a private apartment and trying to avoid the ever-present Paparazzi. They got in the back seat of a Mercedes sedan driven by Henri Paul—a hotel security agent. Diana’s bodyguard, Trevor Rees-Jones, rode shotgun in the passenger front.

Circumstances surrounding Diana’s death are exhaustively investigated. Everyone knows basic facts that Diana and her new boyfriend, Dodi al-Fayed, were leaving a Paris hotel for a private apartment and trying to avoid the ever-present Paparazzi. They got in the back seat of a Mercedes sedan driven by Henri Paul—a hotel security agent. Diana’s bodyguard, Trevor Rees-Jones, rode shotgun in the passenger front.

Blood Alcohol Count (BAC) — 174 milligrams per 100 milliliters of blood or commonly termed a BAC of 0.174% (This was corroborated by his vitreous humor or eye fluid count being 0.173%, his urine being 0.218% and his stomach BAC being 0.191%.)

Blood Alcohol Count (BAC) — 174 milligrams per 100 milliliters of blood or commonly termed a BAC of 0.174% (This was corroborated by his vitreous humor or eye fluid count being 0.173%, his urine being 0.218% and his stomach BAC being 0.191%.)

Learn more about

Learn more about