Raptors are some of the most successful predators on the planet. From owls, eagles, and vultures to hawks, falcons, and other birds of prey, raptors are skilled hunters with incredible senses, like binocular vision, that help them detect prey at far distances.

Raptors are some of the most successful predators on the planet. From owls, eagles, and vultures to hawks, falcons, and other birds of prey, raptors are skilled hunters with incredible senses, like binocular vision, that help them detect prey at far distances.

The secretary bird even carries mouthfuls of water back to the nest for her young — one of the few avian species to quench a chicks’ thirst.

If a raptor was a character in a book, they seem like the perfect villain on the surface. After all, they kill and consume adorable critters like chipmunks, squirrels, mice, monkeys, birds, fish, and old or injured animals. As readers, we’d fear the moment their shadow darkened the soil.

What we may not consider right away is how tender raptors are with their young, or that they only take what they need to feed their family and keep the landscape free of disease from rotting meat and sick animals, or what majestic fliers they are. Raptors have many awe-inspiring abilities.

Take, for example, the Andean condor, the largest flying land bird in the western hemisphere. In the highest peaks of the majestic Andes, the largest raptor in the world hovers in the sky in search of its next meal — a carcass or old/injured animal to hunt. Andean condors have a wingspan of over ten feet. If one flew sideways through an average living room with eight-foot ceilings, the wings would drag on the floor!

How could we turn a massive predator like the Andean condor into a hero? It’s difficult to offset their hunting abilities and diet with the innocence of their prey, but not impossible.

A layered characterization holds the key. It doesn’t matter who your protagonist is or what they do. With proper characterization, a raptor or killer can play any role.

Go Deeper than the Three Dimensions of Character

1st dimension: The face they show to the world; a public persona

2nd dimension: The person they are at home and with close friends

3rd dimension: Their true character. If a fire broke out in a cinema, would they help others get out safely or elbow their way through the crowd?

A raptor-type character needs layers, each one peeled little by little over time to reveal the full picture of who they are and what they stand for. We also need to justify their actions so readers can root for them.

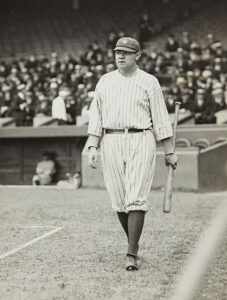

A perfect example is Dexter Morgan, vigilante serial killer and forensic blood spatter analyst for Miami Dade Police.

Why did the world fall in love with Dexter?

What makes Dexter so fascinatingly different is that he lives by a code when choosing his victims – they must, without a doubt, be murderers likely to strike again. But he didn’t always have this code. In the beginning, he killed to satisfy the sick impulses from his “dark passenger.” If it weren’t for Dexter’s adoptive father and police officer, Harry Morgan, who educated his son to control his need to kill and established tight guidelines for Dexter to follow (the code), he would have been the villain.

Readers accept his “dark passenger” because he’s ridding the world of other serial killers who could harm innocent people in the community. And that’s enough justification for us to root for him. We’re willing to overlook the fact that he revels in each kill and keeps trophies. We even join him in celebrating his murders — and never want him caught.

Jeff Lyndsay couldn’t have pulled this off if he showed all Dexter’s layers at the very beginning. It worked because he showed us pieces of Dexter Morgan over time.

The Characterization for Vigilante Killers Cannot be Rushed

When I created this type of character, he started as the villain for two and half novels while I dropped hints and pieces of truth like breadcrumbs. It wasn’t until halfway through book four that the full picture of who he really was and what motivated him became evident.

So, go ahead and craft a raptor as the protagonist of your story (as an antihero). When characters are richly detailed psychologically, readers connect to them. Perhaps a part of us wishes we could enact justice like they do.

If crafted with forethought and understanding, your raptor may become your most memorable character to date. Just go slow and really think about how much of their mind to reveal and when. Who knows? You may create a protagonist readers will analyze for years to come!

*Perhaps it’s unfair to draw a parallel between raptors and vigilante killers but the idea came to me while watching a nature documentary. Make no mistake, I adore raptors.

Have you ever crafted a raptor character aka antihero? Who’s your favorite antihero (movies or books)? And why?

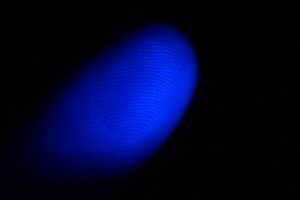

If, say, someone sliced the tip of their finger with a knife, it may leave behind a scar. But then, their fingerprint would be even more distinguishable because of that scar.

If, say, someone sliced the tip of their finger with a knife, it may leave behind a scar. But then, their fingerprint would be even more distinguishable because of that scar. No. Twins do not have identical fingerprints. Our prints are as unique as snowflakes. Actually, we have a 1 in 64 billion chance of having the same fingerprints as someone else.

No. Twins do not have identical fingerprints. Our prints are as unique as snowflakes. Actually, we have a 1 in 64 billion chance of having the same fingerprints as someone else. Losing one’s prints can cause issues with crossing international borders and even logging on to certain computer systems.

Losing one’s prints can cause issues with crossing international borders and even logging on to certain computer systems.

The Villain’s Journey-How to Create Villains Readers Love to Hate is for sale at

The Villain’s Journey-How to Create Villains Readers Love to Hate is for sale at I stumbled across the subject of The Backwards Law by accident—a happy accident that led me to The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck. Excellent book that I devoured in two sittings.

I stumbled across the subject of The Backwards Law by accident—a happy accident that led me to The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck. Excellent book that I devoured in two sittings.