The five senses are the ministers of the soul.– Leonardo da Vinci

By PJ Parrish

When you enter someone’s house, what is the first thing you notice? The feng sui alignment of the furniture? The chatter of their chihuahuas? The stink of the morning’s burnt toast?

I’d bet on the toast. Of the five senses, smell is the one with the best memory. I wish I had said that. But it’s by writer Rebecca McClanahan from her book Word Painting: A Guide to Writing More Descriptively. If you’ve read my posts here, you know I love good description. In our First Page Critiques, I often implore the submitters to pay more attention to this. But it’s not enough, I think, to come up with juicy phrases, the bon geste metaphor or even the telling detail. Good description is also…logical.

In James’s post Sunday, he wrote about stimulus and response. I’d like to riff a little on that today. In a comment, Kay DiBianca mentioned Jack M. Bickham’s book Scene and Structure: How to construct fiction with scene-by-scene flow, logic and readability. I confess I didn’t know of this book, but now wish I had. It’s a fountain of great advice on the need for LOGIC in your fiction narrative.

In our First Page Critiques here, we often take a writer to task for inserting backstory too early in a story. We preach about the need to weave backstory in as the plot progresses. But do folks really understand what that means?

Bickham clarifies this, for me. He suggests thinking of your plot in terms of scenes and sequels. If you do, backstory fades as an issue as you’re freed to focus on narrative thrust. Think of it this way: Scenes are long; sequels are short. Scenes are active; sequels let your character catch their breath. The SEQUEL, not the scene, is where you should be putting any reflection, thought, remembering, musing, reacting and most backstory.

This also goes to the point of pacing. An action-packed chapter (scene) focuses on what is happening only in the moment. A reflective chapter (sequel) focuses on the characters(s) reflecting on what just happened or considering what their next step might be. One is fast; the other is slower.

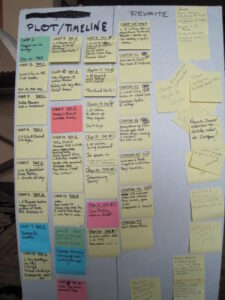

The green one at beginning is a prologue. We later threw it out.

Kelly and I, when plotting, play close attention to the mix of action (scene) vs reaction (sequel) chapters. We plot using Post-Its and use different colors for each type of scene — usually yellow for action and blue for reaction. If we see too many blues in a row, we know we’re in trouble. Likewise, too many yellows call for a breather for the reader.

I’d like to talk about another subtle but important point that’s related to James’s post on stimulus and response. One of my pet peeves is lack of sensory logic in description. What does this mean? It means that the writer — who might be seeing a scene unfold with cinematic clarity in their head — does not adhere to basic SEQUENTIAL LOGIC in describing something.

I’ve concocted a scenario here to make my point. The set-up: A middle-aged woman is returning to an old Manhattan townhouse for the first time since childhood. It is the home of her beloved grandfather, who just died. It is one of those once-grand homes that has gone to decay as her uncle aged into senility. She opens the door to his study, where as a child, she had enjoyed hearing her grandfather read her stories from his vast book collection. What is the sensory sequence of events as she opens that door?

The heavy drapes were drawn against the bright January day, but she could still make out the blue upholstered chair where her grandfather used to sit. She could also see the towering oak shelves lining the walls, filled with all those enchanting books that took her to places she only dreamed about. Places that, as a grown woman, she had visited without joy, checking them off in her passport like so many obligatory duties.

The study was ice cold. It was musty, too, she realized now, with a harsh undertone of a sickly smell, something foul and medicine-like. Still, in her imagination, she could smell the aroma of her grandfather’s cherry pipe tobacco. In the dim light, she made her way to the chair and was shocked to realize it wasn’t Paw-Paw’s reading chair. It was one of those hospital chairs draped in a blue blanket.

This isn’t bad, is it. It’s there. It’s workmanlike. It gets the descriptive job done. But it lacks sensory logic and the backstory memories, while poignant, bog things down. Remember: stimulus and response. I think this version is better.

The smell hit her first, the moment she opened the door, sickly and swirling outward. Not of animal rot or mold. Something worse — chemical and acrid, almost like the acetone she used to remove her nail polish.

The room was dark and ice cold. Her grandfather had been found dead in this room only yesterday. Why was the heat turned off? She drew her coat tighter around her and went to the heavy drapes. She pulled one open, unleashing a storm of dust. She coughed, blinking against the hard January sun.

She turned. She hadn’t been in the room in thirty years. It was smaller than it was in her memory. Wasn’t that always the trick of childhood? Still, the old oak shelves seemed to tower over her, the book spines standing at attention in their dim uniforms, waiting for orders.

Where shall they take us today, Ellie?

Anywhere, Paw-Paw, anywhere but here.

Ah, then they’ll whisk us off to Treasure Island.

The medicine smell was making her head hurt. She looked around, focusing finally on a large blue chair in a shadowed corner. It was her grandfather’s favorite place it sit, with a matching footstool where she perched to listen to him read. She went over to it. It wasn’t Paw-Paw’s chair, she realized. It was one of those ugly medical recliners, covered with a blue hospital blanket. The footstool was gone.

The old pedestal side table was still there, though. It was piled with books. When she picked up the top book, she noticed the ashtray. It held a pipe, a tiny knife and a pouch. She picked up the pipe, bringing it up to her nose. Maple syrup. He was there, suddenly, with her. Her eyes welled with tears.

See the difference? When you enter a scene, don’t go to the default sense of sight. Take your time and try to walk in your character’s shoes. What are they aware of first? This scene is quiet, so I couldn’t use hearing. It’s dark in the room, so clear vision comes later. But smell — that is the most potent and often most poignant sense. Smell has the best memory.

Is your character a cop coming upon a crime scene? What registers foremost in his senses? A dead body on a summer seashore creates a different first impression than a body hanging from a rafter in a cold dimly lit barn. Is your character following a bad guy down into a basement? Every creak of the stairs is like a shot. Every sound is magnified by fear. Go watch the scene where Clarisse has to go down into the basement after Buffalo Bill. Each sense is exploited — the faint bark of the dog, the fluttering buzz of moths, the blaring music. And that’s before everything goes black.

A few tips to help you use senses more effectively:

- Don’t rely on sight. I know you are seeing your story in your head. But go past that to experience it. Don’t just paint a picture. Immerse your reader in the moment. In her book on writing description, Rebecca McCalahan suggests this exercise: Describe a character as a blind person might describe him; use every

sense except sight. - Filter your sensory description through your character’s prism of experience — not your own. A child might smell bubble gum whereas an old woman smells Estee Lauder’s Tuberose perfume.

- Be original. Good description is hard writing. Don’t settle. Rain has a specific sound and smell, depending on the mood of your scene. Cherry Chapstick changes the taste of a kiss. My dog’s ears feel like worn velveteen. I heard two otters playing in my lake and they sounded like shrieking pre-teen girls. A newborn’s head smells like fresh baked bread (to me, at least!)

Let me leave you with one more example, if you want to take some time to read. This is from my book Paint It Black. The set-up: Louis’s partner FBI rookie Emily Farantino has been knocked out by the killer and abducted, tied up in a fish shanty. Kelly and I worked hard to imagine what she feels as she wakes up. We even put cloth bags over our heads to get in her head.

Blackness. She was floating up from the blackness to consciousness. She opened her eyes. Dark. It was still dark and she gave a terrified jerk.

The thing — it was the thing covering her face. The cloth was still there. She could smell its musky odor, and when she drew in a breath, the soft fabric touched her lips.

She became aware of a sharp throbbing in her head, and a faint nausea boiling in her stomach. Her heart was pounding.

Think…think! Calm down. Use your head, use your senses.

She tried to move her arms. They were bound at the wrist, palms up. She could feel the hard wood of the chair. She strained to hear something or someone.

Nothing. Just water lapping and a soft groaning sound. Pilings? The air was still and smelled of mildew and fish. And old building of some kind near the docks? Was she still near the wharf? Something kicked on…like a motor, faint.

She tried to stay calm, tried to quiet the pounding of the blood in her ears so she could hear better. Nothing. No cars, no voices. Just the droning motor sound. It stopped and it was quiet again, except for the lapping water.

The floor creaked. She jumped.

Footsteps on wood, coming closer.

Then it stopped. But she could hear someone moving.

“Motherf—er.”

She jumped. A man, it was a man.

“Damn it, damn it.”

More footsteps. Pacing.

Louder this time. She tried to draw on what she knew, tried to remember what the training books said. But nothing was coming, just the feeling of panic gathering in her gut. She gulped in several breaths to push the panic back. The cloth billowed against her face. She let out a small cry and the pacing stopped.

It was quiet. Water lapping. She held her breath.

Stop. Listen. Smell. Hear. Touch. Taste. And then look. Take it all in with logical sensory sequence. That’s it for today, crime dogs. To paraphrase David Byrne, start making sense.

Last week, Sisters in Crime approached me to do a

Last week, Sisters in Crime approached me to do a  What’s wrong with this sentence, from an old pulp novel:

What’s wrong with this sentence, from an old pulp novel:

It’s about time we talked about Casablanca. This classic consistently shows up at the top of favorite movie lists. It has perhaps the most famous ending line of all time. And of course it’s got Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, and Claude Rains—not to mention Peter Lorre and Sydney Greenstreet and a host of great Warner Bros. character actors.

It’s about time we talked about Casablanca. This classic consistently shows up at the top of favorite movie lists. It has perhaps the most famous ending line of all time. And of course it’s got Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, and Claude Rains—not to mention Peter Lorre and Sydney Greenstreet and a host of great Warner Bros. character actors.