by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Last week we began a discussion of Frank Capra’s 1934 classic It Happened One Night. It was spurred by my meeting with a couple of young ladies at Trader Joe’s who do not watch black-and-white movies. Matters took an alarming turn in the comments when Brother Gilstrap told of a 22-year old fellow in media who’d never heard of Clark Gable or John Wayne!

Last week we began a discussion of Frank Capra’s 1934 classic It Happened One Night. It was spurred by my meeting with a couple of young ladies at Trader Joe’s who do not watch black-and-white movies. Matters took an alarming turn in the comments when Brother Gilstrap told of a 22-year old fellow in media who’d never heard of Clark Gable or John Wayne!

This almost drove me to drink. Instead, with hope in my heart and zeal in my fingers, I clack on.

The plot of It Happened One Night (which Capra and screenwriter Robert Riskin refined after priceless feedback from a writer named Myles Connolly) is simple. Spoiled heiress Ellie Andrews (Claudette Colbert) wants to get to her husband in New York, flier King Westley. But she is held a virtual prisoner on her father’s yacht so he can pay off Westley to have the marriage annulled. She dives overboard and swims to freedom. Wishing to stay incognito she gets on a night bus, but is woefully deficient in street smarts. Another passenger, a fired newspaper reporter named Peter Warne (Clark Gable), spots her and offers her help her get to Westley in exchange for her story, exclusive. She resists until she realizes that only he can keep her on the down low. And so the journey begins.

Death Stakes

As I’ve written many times, the best fiction is about a battle with death, which comes in three forms: physical, professional/vocational, or psychological/spiritual.

For Ellie, it’s psychological death, as it usually is in a romance. The standard trope is that unless they two “soul mates” end up together, they’ll “die on the inside.” Here, there’s a twist: Eillie wants to get to Westley mainly to rebel against her controlling father. She’ll “die inside” if she isn’t allowed to live her own life.

For Peter, it’s professional death. His editor at a New York newspaper has told him never to show his face there again. Peter needs a story, a scoop, or his reporting days are over.

Lesson: Nail your death stakes from the jump, or your plot will have a weak foundation. You can have more than one on the line, though one should be primary. For example, a thriller will almost always have physical death as the crux, but the character can also have psychological challenge as well.

A Romance of Opposites

Who are these two at the start of the picture? Ellie is a spoiled brat. Thus, one part of the plot is The Taming of the Shrew. But the brilliant move by Capra/Riskin is that Peter is an egotist who also needs taming. It’s a perfect balance.

Who are these two at the start of the picture? Ellie is a spoiled brat. Thus, one part of the plot is The Taming of the Shrew. But the brilliant move by Capra/Riskin is that Peter is an egotist who also needs taming. It’s a perfect balance.

There are two main romance tropes: 1. The couple who hate each other at first, then grow into love; and, 2. The lovers who want to be together but are kept apart by other forces, e.g. Romeo and Juliet. This movie is obviously the first kind.

Lesson: Know your tropes because the readers expect them. Disappointed readers do not become return buyers. Your task is to originalize how tropes are played out. This movie does that exquisitely.

Three Unforgettable Scenes and No Weak Ones

Writer-director John Huston once said that a great movie must have at least three unforgettable scenes, and no weak ones. Here are the three I’d pick in It Happened One Night.

1. Early in Act 2 Peter, to conserve their money, rents a single cabin at an auto camp, registering as husband and wife. Ellie is aghast. Peter ties a rope across the room between the two beds and throws a blanket over it. “Behold the walls of Jericho,” he says. “Maybe not as thick as the ones that Joshua blew down with his trumpet. But a lot safer. You see, I have no trumpet….Do you mind joining the Israelites?”

Ellie just stands there, defiant. So Peter decides to show her how a man undresses. It’s “quite a study in psychology.” He takes off his coat, his tie, then his shirt. He’s about to remove his pants when Ellie quickly scoots to the other side.

What made this unforgettable was not only Gable’s delivery of the lines, but the fact that he wore no undershirt. After this movie came out, undershirt sales in America suffered a serious decline!

2. The most famous scene in the movie is the hitchhiking scene. Peter has been bragging to Ellie how he knows everything, including the right way to dunk a donut. “I ought to write a book about it.” On the road, he explains to Ellie he can get a ride by the magic of this thumb and explains the various thumb moves. He says he’s going to write a book about it called “The Hitchhiker’s Hail.” Ellie is not impressed.

As cars stream by, Peter tries every one of the moves and not a single car stops. Crestfallen, he says, “I don’t think I’ll write that book after all.”

Ellie says, “You mind if I try?”

“You? Don’t make me laugh.”

“I’ll stop a car and I won’t use my thumb…It’s a system all my own.”

Ellie then waits for the next car. When it comes she raises her skirt and sticks out her attractive gam. The car screeches to a halt. The taming of the egotist has begun.

3. The wedding scene at the end, when Ellie is about to marry King Westley once more and makes an unforgettable escape.

Lesson: However you plan your scenes, be ye outliner (before) or pantser (during) push yourself to the original, the fresh, the unanticipated.

Spicy Minor Characters

I call minor characters the “spice” of great fiction (see Mr. Charles Dickens for the Master Class). Two of them come by way of two of the best character actors of the time, Roscoe Karns and Alan Hale.

Karns plays Oscar Shapeley, an oily (and married) traveling salesman who fancies himself a ladies’ man. On the night bus he starts yakking to Ellie. “Shapeley’s the name and that’s the way I like ’em.” On and on he goes, until Ellie cuts him down with a line.

Karns plays Oscar Shapeley, an oily (and married) traveling salesman who fancies himself a ladies’ man. On the night bus he starts yakking to Ellie. “Shapeley’s the name and that’s the way I like ’em.” On and on he goes, until Ellie cuts him down with a line.

“Hoo hoo!” says Shapeley. “There’s nothing I like better than to meet a high-class mama that can snap ’em back at you, ’cause the colder they are, the hotter they get. Yessir, that’s what I always say. When a cold mama gets hot, boy how she sizzles. Now you’re just my type. Believe me, sister, I could go for you in a big way. Fun-on-the-side Shapeley they call me, with accent on the fun. Believe you me!”

Peter has been watching all this with amusement, but finally saves Ellie by telling Shapeley to move to another seat because “I’d like to sit next to my wife.” Shapeley quickly complies.

Later, Shapeley will show up again, after figuring out who Ellie really is. Peter will then scare the pants off Shapeley by pretending to be a mobster who is “holding that dame for a million smackers.” And if Shapeley talks, the mob will find him and his family. Scared to death, Shapeley runs off into the woods.

In the hitchhiking scene, the car that stops is driven by Alan Hale (you may remember him as Little John in The Adventures of Robin Hood). He is loud, jovial, talkative.

In the hitchhiking scene, the car that stops is driven by Alan Hale (you may remember him as Little John in The Adventures of Robin Hood). He is loud, jovial, talkative.

“So, you’re just married? That’s pretty good. But if I was young, that’s the way I’d spend my honeymoon. Hitchhiking. Yes, sir.” He begins to sing: “Hitchhiking down the highway of love on a honeymoon!”

It turns out he’s a “road thief” who picks people up then drives off with their luggage. It’s a short bit, but a flavorful spice.

Lesson: Do not waste your minor characters by making them clichéd or throwaways. Give them a life of their own, with unique tags of manner and speech. Readers love spice. It’s one of the best ways to elevate your work above “AI slop.”

Dialogue

I’ve long held that the fastest way to improve any manuscript is with sharp, orchestrated dialogue. The movie is full of smart Riskin banter. One example: When Peter first sits next to Ellie on the bus, she is not pleased. He offers to put her bag up top for her. She gets up to do it herself. The bus lurches forward and she falls back on Peter’s lap. She quickly scoots off. Peter grins. “Next time you drop in, bring your folks.”

Lesson: Standout dialogue is a craft that can be learned. I ought to write a book about it.

Pet the Dog

A “pet the dog” beat is a moment in Act 2 when the lead helps someone who needs it, even though it comes with a cost. In the movie, the passengers on the night bus are bonding by singing “The Man on the Flying Trapeze” (a popular ditty of the day). Then the bus hits a muddy rut and comes to a hard stop, tossing the passengers. They mostly laugh, but suddenly a little boy is screaming “Ma! What’s the matter with you? Somebody help!” Peter rushes over, determines the mother has passed out and assures the boy she’ll come around.

“We ain’t ate nothin’ since yesterday,” the boy says. He says his mother has a job waiting for her in New York but had to spend all their money on the tickets. Peter reaches into his pocket for a bill, a ten-spot he and Ellie need for the trip. He hesitates. Ellie takes the bill, hands it to the boy and tells him to buy something to eat at the next stop. The boy says he “shouldn’t oughta” take it. He holds the bill out to Peter, “You might need it.” Peter waves him off and puts on a smile. “I got millions.”

Lesson: Pet the dog moments deepen our bond to characters. Think of Katniss with little Rue, or Richard Kimble getting the distressed boy to the operating room in The Fugitive. The key is that the act puts the character in a worse position in the plot.

Final Thoughts

Capra always said that the Gable in It Happened One Night was the real Gable—unabashedly masculine, with a vein of sardonic humor. Colbert showed herself adept at drama, comedy, and pathos, playing a “brat” whose inner decency finally breaks out. In true rom-com fashion, each transforms the other for their ultimate good.

Would that today we had more movies as tight and multi-faceted as It Happened One Night.

And books, too.

Black-and-white movies forever!

Comments Welcome.

Note: It Happened One Night is free to watch on YouTube.

And for your viewing pleasure, here’s the famous hitchhiking scene:

Today I want to talk about another pure classic every writer, especially romance writers, should know—Frank Capra’s 1934 mega-hit It Happened One Night. Arguably the first true rom-com, the movie swept the major Oscars: Picture, Director, Actor, Actress, Screenplay.

Today I want to talk about another pure classic every writer, especially romance writers, should know—Frank Capra’s 1934 mega-hit It Happened One Night. Arguably the first true rom-com, the movie swept the major Oscars: Picture, Director, Actor, Actress, Screenplay.

Today I want to bring up a classic Davis “woman’s picture” (as they were called in WWII, to cater to all the women whose men were off fighting a war), Now, Voyager. As always, I encourage you to watch it, then refer back to these notes for craft study.

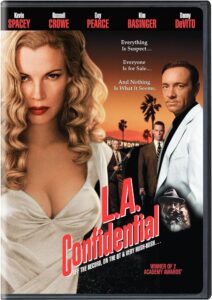

Today I want to bring up a classic Davis “woman’s picture” (as they were called in WWII, to cater to all the women whose men were off fighting a war), Now, Voyager. As always, I encourage you to watch it, then refer back to these notes for craft study. The film garnered critical praise and was Oscar nominated for Picture, Director, Screenplay, and Cinematography. Kim Basinger took home the statuette for Best Supporting Actress.

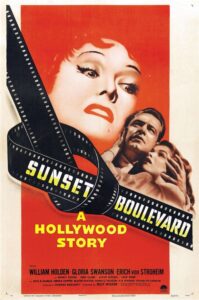

The film garnered critical praise and was Oscar nominated for Picture, Director, Screenplay, and Cinematography. Kim Basinger took home the statuette for Best Supporting Actress. The director George Cukor suggested Swanson to Wilder, and how perfect she was. She had been one of the great “faces” of silents, and was the right age—50—for Norma. That’s when Wilder got the brilliant idea of using Cecil B. DeMille as himself, for he had famously worked with Swanson in the silent era and was still directing movies. Swanson would essentially be playing a version of herself.

The director George Cukor suggested Swanson to Wilder, and how perfect she was. She had been one of the great “faces” of silents, and was the right age—50—for Norma. That’s when Wilder got the brilliant idea of using Cecil B. DeMille as himself, for he had famously worked with Swanson in the silent era and was still directing movies. Swanson would essentially be playing a version of herself.

Wonderful Life begins and ends on the same Christmas Eve, in a town called Bedford Falls. It opens with shots of the snowy town, and the voices of various townspeople praying for a man named George Bailey. The last voice is the one we’ll come to know as Zuzu (George’s youngest child) pleading, “Please bring Daddy back!”

Wonderful Life begins and ends on the same Christmas Eve, in a town called Bedford Falls. It opens with shots of the snowy town, and the voices of various townspeople praying for a man named George Bailey. The last voice is the one we’ll come to know as Zuzu (George’s youngest child) pleading, “Please bring Daddy back!” George Bailey (James Stewart) is a good man, a solid citizen, but is far from perfect. He’s not above leering at the attractive derrière of Violet Bick (Gloria Grahame) as she shimmies down the street. He loses his temper and becomes abusive. He verbally destroys the simple-minded Uncle Billy when the latter loses a crucial bank deposit. On Christmas Eve, his life at its lowest ebb, he screams over the phone at his child’s teacher, then yells at his children, bringing them to tears. (Stewart’s acting is brilliant throughout. He was suitably nominated for Best Actor, losing only because the equally brilliant Frederic March in The Best Years of Our Lives.)

George Bailey (James Stewart) is a good man, a solid citizen, but is far from perfect. He’s not above leering at the attractive derrière of Violet Bick (Gloria Grahame) as she shimmies down the street. He loses his temper and becomes abusive. He verbally destroys the simple-minded Uncle Billy when the latter loses a crucial bank deposit. On Christmas Eve, his life at its lowest ebb, he screams over the phone at his child’s teacher, then yells at his children, bringing them to tears. (Stewart’s acting is brilliant throughout. He was suitably nominated for Best Actor, losing only because the equally brilliant Frederic March in The Best Years of Our Lives.) Every one of the secondary characters in Wonderful Life is well-drawn and engaging in their own right. Clarence the Angel (Henry Travers); Bert the cop (Ward Bond); Ernie the cab driver (Frank Faylen); the tragic Mr. Gower (H. B. Warner); all the way down to Zuzu (Karolyn Grimes, who is still with us). Old Man Potter (Lionel Barrymore) is a classic villain, and even his nonspeaking servant has an eerie presence.

Every one of the secondary characters in Wonderful Life is well-drawn and engaging in their own right. Clarence the Angel (Henry Travers); Bert the cop (Ward Bond); Ernie the cab driver (Frank Faylen); the tragic Mr. Gower (H. B. Warner); all the way down to Zuzu (Karolyn Grimes, who is still with us). Old Man Potter (Lionel Barrymore) is a classic villain, and even his nonspeaking servant has an eerie presence. Which doesn’t help George’s frustration about staying in town. That evening he finds himself walking by Mary Hatch’s house. Mary, back in town from school, has been waiting for this moment. She has on her best dress and has set up the parlor to reveal a picture of a romantic moment from their high school days—when George said he would “lasso the moon” for Mary.

Which doesn’t help George’s frustration about staying in town. That evening he finds himself walking by Mary Hatch’s house. Mary, back in town from school, has been waiting for this moment. She has on her best dress and has set up the parlor to reveal a picture of a romantic moment from their high school days—when George said he would “lasso the moon” for Mary. “You wouldn’t mind living in the nicest house in town,” Potter says, “buying your wife a lot of fine clothes, a couple of business trips to New York a year, maybe once in a while Europe. You wouldn’t mind that, would you, George?”

“You wouldn’t mind living in the nicest house in town,” Potter says, “buying your wife a lot of fine clothes, a couple of business trips to New York a year, maybe once in a while Europe. You wouldn’t mind that, would you, George?” In Wonderful Life, George’s realization about his town’s love is argued against in Act 1. That’s when the young George Bailey tells the two girls, Mary and Violet, the following:

In Wonderful Life, George’s realization about his town’s love is argued against in Act 1. That’s when the young George Bailey tells the two girls, Mary and Violet, the following: