by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

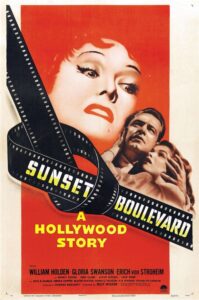

I had a tough decision to make for this installment of JSB at the Movies. It came down to a choice between How to Stuff a Wild Bikini and Sunset Boulevard. After a night of tossing and turning, I chose the latter. I had to give the nod to Gloria Swanson over Annette Funicello.

I had a tough decision to make for this installment of JSB at the Movies. It came down to a choice between How to Stuff a Wild Bikini and Sunset Boulevard. After a night of tossing and turning, I chose the latter. I had to give the nod to Gloria Swanson over Annette Funicello.

Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1951) is an undisputed classic of the film noir era. It stars William Holden as a struggling screenwriter, and Gloria Swanson as what she actually was—an aging star from silent films. Her performance is one of the most iconic in movie history. Indeed, she was the favorite to take home the Oscar, and she should have.

But in a quirk of fate, she was up against another all-time performance—Bette Davis as Margot Channing in All About Eve. In a further quirk, those two probably split the vote, giving the prize to Judy Holliday in Born Yesterday. Holliday is quite good, and in any other year would have deserved the gold statuette. But not over Davis, and especially not Swanson’s Norma Desmond!

Wilder originally wanted Mae West for Norma and Montgomery Clift for the screenwriter Joe Gillis. But Miss West, a true diva, wanted to change a lot of the dialogue. Billy Wilder would not stand for that, and a good thing, too.

Wilder also considered Greta Garbo (who was not interested in returning to the screen), Pola Negri, a great silent film actress (but whose Polish accent was troublesome), and the “It Girl” Clara Bow. But Bow turned it down, having considered her unsuccessful transition to sound and ill-treatment by the industry reasons to stay retired.

The director George Cukor suggested Swanson to Wilder, and how perfect she was. She had been one of the great “faces” of silents, and was the right age—50—for Norma. That’s when Wilder got the brilliant idea of using Cecil B. DeMille as himself, for he had famously worked with Swanson in the silent era and was still directing movies. Swanson would essentially be playing a version of herself.

The director George Cukor suggested Swanson to Wilder, and how perfect she was. She had been one of the great “faces” of silents, and was the right age—50—for Norma. That’s when Wilder got the brilliant idea of using Cecil B. DeMille as himself, for he had famously worked with Swanson in the silent era and was still directing movies. Swanson would essentially be playing a version of herself.

Clift withdrew for one reason or another (there are a few theories) and William Holden was offered the role, which he gladly accepted. Another brilliant move. It’s hard now to think of the cynical, hardboiled voiceover narration in any voice but Holden’s.

Two other bits of casting brilliance. One is Erich von Stroheim as Max, Norma’s butler. He had been one of the most famous—or infamous, from the studio heads’ perspective—silent film directors and, like Swanson, had fallen into obscurity. The film Norma privately screens is Queen Kelly, which Stroheim directed in 1928.

Then there are Norma’s bridge partners, each a faded star from the silent era. Joe calls them her “waxworks”—Buster Keaton, Anna Q. Nilsson, and H. B. Warner (who played Jesus in DeMille’s silent version of King of Kings, and Mr. Gower, the druggist, in Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life).

Frame Story

This is a frame story. We begin in the present, then the movie unfolds in the past; the last scene returns us to the present. It’s a fine technique, used numerous times in various genres. Stephen King’s The Green Mile is an example.

Only this opening frame was unique: it is narrated by a dead man! Joe Gillis is floating face down in a pool. The cops are on the scene. What happened? Joe will tell us from beyond…

Lesson: Using a frame is a solid choice, but only if you make it compelling in and of itself. Don’t just toss one in! Take the time to make it fresh and even bold.

Death Stakes

Joe is an out of work screenwriter desperately in need of a job. He’s behind in his rent and his car is about to be repossessed. He makes the rounds of his studio contacts, but can’t find anything—not even a quick rewrite assignment. When he confronts his agent on a golf course, he gets a kiss off. The stakes here are professional. If he doesn’t get work he’ll have to head back to Dayton, Ohio with his tail between his legs.

Driving back to his dismal apartment, he spots the repo men. The chase is on. Joe pulls into a driveway on Sunset Boulevard to escape.

Turns out the house is a decrepit mansion from the crazy 1920s. Inside he meets the faded silent screen star, Norma Desmond. Seems she’s been holed up inside for twenty years, living off past dreams with the help of her somewhat creepy servant, Max. Norma has been working on a screenplay for her comeback, a turgid scenario about Salome, a part she is clearly too old for. Joe hatches a plan. He’ll work on her screenplay to make some quick dough.

Lesson: If the death stakes are professional, make sure the reader understands how important it is to the character. Most of Act 1 is showing Joe Gillis in various stages of desperation for dough.

Doorway of No Return

But Norma has a plan of her own—while Joe spends the night in a little room over the garage, Max moves Joe’s things out of his apartment and into the room. Joe is furious. Then the repo men show up and take away Joe’s car, making him a virtual prisoner.

Lesson: Act 2 doesn’t start until the Lead is forced into the confrontation…and can’t go back to the way things were in Act 1.

Pet the Dog

When the Lead takes time from his death stakes struggle to help someone else, we become more invested in him. Joe helps a young studio reader, Betty (Nancy Olson) with a script idea. This relationship becomes more complicated as Joe and Betty fall in love, though she is engaged to Joe’s friend Artie (Jack Webb. Yes, that Jack Webb, whose personality in this film is the exact opposite of cop Joe Friday from Dragnet).

Tip: A love interest subplot should intersect with the main plot in a way that causes more trouble for the Lead. Boy, is that ever true here, as it leads, ultimately, to Joe’s death.

Mirror Moment

In the dead center of the film we get Joe Gillis’s life-altering look at himself. Norma has attempted suicide because Joe has rejected her. Now, in her bedroom, we see on his face the choice: should he finally make a break, or stay on as her lover? The former choice would lead to his redemption, the latter to the loss of his individuality.

He stays. The rest of the movie will be about the price of that decision.

Lesson: The Mirror Moment sees all, knows all.

Sharp Dialogue

The dialogue in this movie is priceless. William Holden has the perfect voice and delivery for some of the best lines in all of noir. My favorite is when Norma is describing a scene from her mammoth and atrocious screenplay about Salome.

Lesson: Dialogue is the fastest way to improve any manuscript. Show an agent, editor or browser, on your first pages, that yours has zing and you are halfway home to getting the whole book read. May I modestly suggest a book to help you in that regard?

If you’ve never seen Sunset Boulevard, I urge you to settle in with a bowl of popcorn and watch it. The adage “They don’t make ’em like they used to” certainly applies to this classic. (And don’t look at the clip below. Watch it in the movie!)

What better way to end this post than with one of the most famous closing images in cinema history:

Discuss!