What is a hero? One answer is a legendary figure, such as Hercules, who accomplishes great deeds. Yet another is an ordinary person who does the right thing, no matter how lonely that might be. This being the Kill Zone, the answer to the above question is the principal character of a story. A character who strives to right a wrong, stop a threat, or protect the weak, who faces and overcomes challenges despite the odds to triumph in the end, sometimes at great personal cost.

We have three excerpts dealing with heroes today. Joe Moore ponders the role of beauty and intelligence in a hero. PJ Parrish looks at the different sort of supporting characters who team up with heroes. Larry Brooks considers how the hero’s role changes over the course of four-act structure.

As always the full version of each post is worth reading as are the original comments, date-linked at the bottom of their respective excerpt. Joe’s original was short enough I included all of it, but it’s worth checking out the comments.

This summer I attended an interesting workshop by a bestselling, Pulitzer Prize-winning author, who discussed his approach to crafting thrillers. It was his opinion that main characters need to be handsome (or beautiful, if female), intelligent, and successful. As he described his approach, “I write a main character that women want to sleep with, and men want to be. ” In other words, more James Bond than Monk. His reason for his writing main characters that way? “I like to write books that sell.”

It’s an interesting thought. I’d always assumed that a main character didn’t need to be particularly genetically or intellectually gifted. I always assumed that overcoming adversity was what made a hero appealing to readers. But when I think back about books I’ve particularly enjoyed–SILENCE OF THE LAMBS, THE HUNT FOR RED OCTOBER, COMA–I have to admit that those protagonists were handsome and brilliant. I just never thought of those characteristics as being requirements for popular appeal.

What do you think? Is physical beauty, in particular, central to creating an appealing main character?

Joe Moore—August 19, 2014

If you are considering a series, it’s a good idea to think hard about second bananas. First, they have great appeal. (Sorry, I had to get that out of my system before I could go on). But they are also very useful. More on that in a moment but first, it might be useful to examine the different types of pairings you might create:

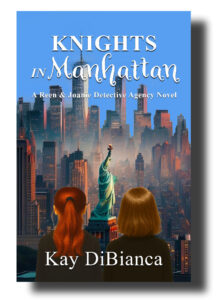

The Teammate: This is actually a dual protagonist situation, wherein there are two equally active case solvers. The classic example is Dashiell Hammett’s Nick and Nora Charles. (Maybe Asta the dog was the sidekick?) Modern examples are Paul Levine’s Steve Solomon and Victoria Lord, and SJ Rozan’s Lydia Chin and Bill Smith (who appear in alternating books and sometimes together).

The Sidekick. This character is not an equal to the protag but almost as important in propelling the plot. He or she is a fixture in a series, a reoccurring character. The classic example, of course is Holmes and Watson. But others include Nero Wolf and Archie Goodwin, or Cocker and Tubbs from the old Miami Vice series.

The Confidant: One step lower on the totem, this character might not actively work a case with the hero, but acts as a sounding board for the hero. My fave confidant is Meyer, who sits on the Busted Flush sipping scotch and spouting wisdom about chess and economics as he listens to Travis McGee ponder out the case. (or his latest lady problem) Meyer serves as an anchor of sorts when McGee’s moral compass wanders. More on that later!

The Foil: Some folks use “foil” and “sidekick” interchangeably, but I think the foil deserves its own category. This a character who contrasts with the protag in order to highlight something about the hero’s nature. Hence the word “foil” — which comes from the old practice of backing gems with foil to make them shine brighter. We can go all the way back to the first detective story to find a great foil: In Poe’s The Purloined Letter, the hero Dupin has the dim-witted prefect of police Monsieur G. Some folks might even say Watson is a foil for Holmes because his obtuseness makes Holmes shine brighter.

Or consider Hamlet and Laertes. Both men’s fathers are murdered. But while Hamlet broods and does nothing, Laertes blusters and takes action. And the contrast sheds light on Hamlet’s character. Hamlet himself says, “I’ll be your foil, Laertes. In mine ignorance your skill shall, like a star in the darkest night, stick fiery off indeed.”

PJ Parrish—August 18, 2015

In her book “The Hero Within: Six Archetypes We Live By”, Carol S. Pearson is credited with bringing us life’s hero archetypes, four of which align exactly with the sequential/structural “parts” of a story. (For those who live by the 3-Act model, know that the 2nd Act is by definition contextually divided into two equal parts at the midpoint, with separate hero contexts for each quartile on either side of that midpoint, thus creating what is actually a four–part story model; this perspective is nothing other than a more specific – and thus, more useful – model than the 3-Act format from which it emerges.)

Those four parts align exactly with these four character contexts:

Orphan (Pearson’s term)/innocent – as the story opens your hero is living life in a way that is not yet connected to (or in anticipation of) the core story, at least in terms of what goes wrong.

And something absolutely has to go wrong, and at a specific spot in the narrative.

The author’s mission in this first story part/quartile, prior to that happening, is twofold: make us care about the character, while setting up the mechanics of the dramatic arc (as well as the character arc) to come. There are many ways to play this – which is why this isn’t in any way formulaic – since within these opening chapters the hero, passive or not, can actually sense or even contribute to the forthcoming storm, or it can drop on their head like a crashing chandelier. Either way, something happens (at a specific place in the narrative sequence) that demands a response from your hero.

Now your hero has something to do, something that wasn’t fully in play prior to that moment (called The First Plot Point, which divides the Part 1 quartile from the Part 2 quartile). In this context, and if your chandelier falls at the proper place (in classic story structure that First Plot Point can arrive anywhere from the 20th to 25th percentile; variances on either end of that range puts the story at risk for very specific reasons), you can now think of your hero as a…

Wanderer – the hero’s initial reactions to the First Plot Point (chandelier impact), which comprise the first half of Act 2 (or the second of the four “parts” of a story). The First Plot Point is the moment the story clicks in for real (everything prior to it was essentially part of a set-up for it), because the source of the story’s conflict, until now foreshadowed or only partially in play, has now summoned the hero to react. That reaction can be described as “wandering” through options along a new path, such as running, hiding, striking back, seeking information, surrendering, writing their congressman, encountering a fuller awareness of what they’re up against, or just plain getting into deeper water from a position of cluelessness and/or some level of helplessness.

But sooner or later, if nothing else than to escalate the pace of the story (because your hero can’t remain either passive or in victim-mode for too long), your hero must evolve from a Wanderer into a…

Warrior – using information and awareness and a learning curve (i.e, when the next chandelier drops, duck), as delivered via the Midpoint turn of the story. The Midpoint (that’s a literal term, by the way) changes the context of the story for both the reader and the hero (from wanderer into warrior-mode), because here is where a curtain has been drawn back to give us new/more specific information – machinations, reveals, explanations, true identities, deeper motives, etc. – that alter the nature of the hero’s decisions and actions from that point forward, turning them from passive or clueless toward becoming more empowered, resulting in a more proactive attack on whatever blocks their path or threatens. Which is often, but not always, a villain.

But be careful here. While your hero is getting deeper into the fight here in Part 3, take care to not show much success at this point (the villain is ramping things up, as well, in response to your hero’s new boldness). The escalated action and tension and confrontation of the Part 3 quartile (where, indeed, the tension is thicker than ever before) is there to create new story dynamics that will set up a final showdown just around the corner.

That’s where, in the fourth and final quartile, the protagonist becomes, in essence, a…

Martyr (Pearson’s term)/hero – launching a final quest or heading down a path that will ultimately lead to the climactic resolution of the story. This should be a product of the hero’s catalytic decisions and actions (in other words, heroes shouldn’t be saved, rather, they should be the primary architect of the resolution), usually necessitating machinations and new dynamics (remember Minny’s “chocolate” pie in The Help?), which ramp up to facilitate that climactic moment.

This is where character arc becomes a money shot. Because by now everything you’ve put the hero through has contributed to a deep well of empathy and emotion on the reader’s part. This is where the crowd cheers or hearts break or history is altered, where villains are vanquished and a new day dawns.

Larry Brooks—November 2, 2015

***

- As Joe asked, “is physical beauty, in particular, central to creating an appealing main character?”

- Do you have a favorite type of supporting character AKA second banana? Personally, I love a great sidekick. Do you have a second banana of any of the type’s Kris listed from your own fiction you’d like to share?

- Do you agree that a fictional hero can go through a sequence of roles over the course of a novel or movie? Any thoughts on Larry’s mapping that to four-act structure?

Most people are familiar with “fight or flight” response to a threat. Physiologist and Harvard Medical School chair,

Most people are familiar with “fight or flight” response to a threat. Physiologist and Harvard Medical School chair,