Two weeks ago James Scott Bell wrote a terrific post on hero passivity, and how to handle it (carefully) in a novel. Which in a nutshell is this: in general you should avoid it, because it’s absolutely a radioactive story killer if handled wrong.

The mistake, and the temptation that leads to it, is to get too caught up in the intention to write a character-driven story (a noble goal, but like trying to run a marathon, you need to understand the role of pace), and a facet of that character is passivity in the form of lack of motivation, lack of courage, lack of direction or simply lack of interest.

Sooner or later, you need to give your hero something to do.

This issue is an example of how story structure touches and drives everything.

This includes character arc, the beginning of which can indeed be a viable context for your protagonist’s passivity (which may be the very thing that gets them into trouble). Nay-sayers on structure handle this differently, and yet end up – at least when the story finally works – aligning with where structure seeks to take a story in the first place.

Which is why mastery of story structure is perhaps the most critical phase of an author’s development. Because everything in the story connects to and is informed by structure.

When someone tries to tell you that’s not true… run.

Showing your hero in a passive context can actually be a good thing…

… provided you understand when and where to allow passivity to show itself.

Some stories begin with the hero simply not yet having fully collided with a forthcoming problem or situation (which absolutely needs to happen, and at a specific place in the story sequence), while others show the hero actually contributing to that problem by virtue of being passive (like, for example, someone in a relationship being cold toward their partner, resulting in… well, you know, all kinds of issues).

But be careful with this. Because passivity can get you – the author – in a real pickle, too. Stories are nothing if not a vicarious experience of a central hero-centric problem/situation (plot) for the reader. Just don’t suck on that pickle for too long… because it’s toxic if you do.

And that’s where structure will guide you.

In her book “The Hero Within: Six Archetypes We Live By”, Carol S. Pearson is credited with bringing us life’s hero archetypes, four of which align exactly with the sequential/structural “parts” of a story. (For those who live by the 3-Act model, know that the 2nd Act is by definition contextually divided into two equal parts at the midpoint, with separate hero contexts for each quartile on either side of that midpoint, thus creating what is actually a four–part story model; this perspective is nothing other than a more specific – and thus, more useful – model than the 3-Act format from which it emerges.)

Those four parts align exactly with these four character contexts:

Orphan (Pearson’s term)/innocent – as the story opens your hero is living life in a way that is not yet connected to (or in anticipation of) the core story, at least in terms of what goes wrong.

And something absolutely has to go wrong, and at a specific spot in the narrative.

The author’s mission in this first story part/quartile, prior to that happening, is twofold: make us care about the character, while setting up the mechanics of the dramatic arc (as well as the character arc) to come. There are many ways to play this – which is why this isn’t in any way formulaic – since within these opening chapters the hero, passive or not, can actually sense or even contribute to the forthcoming storm, or it can drop on their head like a crashing chandelier. Either way, something happens (at a specific place in the narrative sequence) that demands a response from your hero.

Now your hero has something to do, something that wasn’t fully in play prior to that moment (called The First Plot Point, which divides the Part 1 quartile from the Part 2 quartile). In this context, and if your chandelier falls at the proper place (in classic story structure that First Plot Point can arrive anywhere from the 20th to 25th percentile; variances on either end of that range puts the story at risk for very specific reasons), you can now think of your hero as a…

Wanderer – the hero’s initial reactions to the First Plot Point (chandelier impact), which comprise the first half of Act 2 (or the second of the four “parts” of a story). The First Plot Point is the moment the story clicks in for real (everything prior to it was essentially part of a set-up for it), because the source of the story’s conflict, until now foreshadowed or only partially in play, has now summoned the hero to react. That reaction can be described as “wandering” through options along a new path, such as running, hiding, striking back, seeking information, surrendering, writing their congressman, encountering a fuller awareness of what they’re up against, or just plain getting into deeper water from a position of cluelessness and/or some level of helplessness.

But sooner or later, if nothing else than to escalate the pace of the story (because your hero can’t remain either passive or in victim-mode for too long), your hero must evolve from a Wanderer into a…

Warrior – using information and awareness and a learning curve (i.e, when the next chandelier drops, duck), as delivered via the Midpoint turn of the story. The Midpoint (that’s a literal term, by the way) changes the context of the story for both the reader and the hero (from wanderer into warrior-mode), because here is where a curtain has been drawn back to give us new/more specific information – machinations, reveals, explanations, true identities, deeper motives, etc. – that alter the nature of the hero’s decisions and actions from that point forward, turning them from passive or clueless toward becoming more empowered, resulting in a more proactive attack on whatever blocks their path or threatens. Which is often, but not always, a villain.

But be careful here. While your hero is getting deeper into the fight here in Part 3, take care to not show much success at this point (the villain is ramping things up, as well, in response to your hero’s new boldness). The escalated action and tension and confrontation of the Part 3 quartile (where, indeed, the tension is thicker than ever before) is there to create new story dynamics that will set up a final showdown just around the corner.

That’s where, in the fourth and final quartile, the protagonist becomes, in essence, a…

Martyr (Pearson’s term)/hero – launching a final quest or heading down a path that will ultimately lead to the climactic resolution of the story. This should be a product of the hero’s catalytic decisions and actions (in other words, heroes shouldn’t be saved, rather, they should be the primary architect of the resolution), usually necessitating machinations and new dynamics (remember Minny’s “chocolate” pie in The Help?), which ramp up to facilitate that climactic moment.

This is where character arc becomes a money shot. Because by now everything you’ve put the hero through has contributed to a deep well of empathy and emotion on the reader’s part. This is where the crowd cheers or hearts break or history is altered, where villains are vanquished and a new day dawns.

Instinct, Intention or Accident?

Too many writers aren’t in command of the difference. You can be, and you should be.

In this context these three options don’t refer to your hero, they refer to you, the author of the story. All three modes may play a role in how a story comes together, but the good news is that you don’t have to rely on any single one of them. Armed with a deeper knowledge of craft, you get to choose which to harness, and when.

Truly, successful storytelling exceeds the sum of these three states, so listen to all the voices in your head that contribute to the way you build the arc of your character: yours, those of your characters (that’s a metaphor, by the way, because when a character “speaks to you” that’s just your story sensibility weighing in), and the sum of the learning you have accumulated from venues like this one, and the books the authors here have written to show it to you.

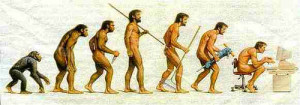

(image by Esther Dyson)

‘Stories are nothing if not a vicarious experience of a central hero-centric problem/situation (plot) for the reader. Just don’t suck on that pickle for too long… because it’s toxic if you do’

You’re right, it is toxic if you do. Dwight Swain wrote something similar, I pondered and pondered then couldn’t write for 2 weeks.

‘ [F]or a story is never really about anything. Always it concerns, instead, someone’s reactions to what happens: his feelings, his emotions, his impulses, his dreams; his ambitions; his clashing drives and inner conflicts. The external serves only to bring them into focus.”

Thanks for weighing in. I respectfully disagree with Swain, relative to his use of the word “always” in that sentence. Because a GOOD story, ALWAYS, is about what your hero DOES. That’s huge. That’s the movement of the story. From Swain’s context, a story is about something just sitting there, feeling and dreaming and watching dreams collide with reality… all very literary-sounding, but without DOING SOMETHING, it’s stuck. Both realms are necessary for a story to work.

Passivity in a hero is a tricky thing to avoid. The first manuscript I wrote had to go through a couple of drafts because he WAS too passive and let life happen to him. But this is where writing fiction using real life is difficult. We often do live passively letting life happen to us, so in an effort to be honest on the page, it’s hard not to fall into the passivity trap.

My hero is better now than he was, but I’m not sure I’ve totally learned all I can learn about this aspect of writing a good protag.

Nay-sayers on structure handle this differently, and yet end up – at least when the story finally works – aligning with where structure seeks to take a story in the first place.

That’s truly an amusing irony, isn’t it Larry? I’ve seen that over and over again. In the early 90s I attended seminars by “battling” screenplay gurus. One dissed the structural paradigm of another, using colorful language to do so, claiming there was no such thing. Then, after laboriously laying out his own theory, the elements lined up in exactly the same sequence.

You’re right, Jim, it’s both ironic and amusing… just not to those nay-sayers. There’s a writing book out there (you know the one, not gonna mention the title), which is, in effect, a direct contradictory response to what you and I write about relative to structure (it’s even in the title), and yet, many of the reviews and much of the commentary I’ve heard about it reveals that the book is exactly this phenomena: go with the flow, ignore structure, then apply a few principles (that are, in fact, the bones of structure), and viola, you end with a story that works. And, that aligns with those basic structural principles. You and I see the irony and the humor… those writers see neither, unfortunately. Because “getting there” is enough, when in fact, they could “get there” more effectively, more efficiently, and more blissfully, if they knew how to get there in the first place, instead of believing that have made it all up on their own. That, too, is fiction.

Learning this (from you!) was the best thing that ever happened to my writing. It’s not always easy to get a passive character to move it, which is why I chose to slam mine over the head with the chandelier (love that metaphor). But it is necessary. Outstanding post, Larry!

Sue… you’ve learned it well. Your new novel, “Marred,” is proof, and is part of why it is doing so well (already on some bestseller lists!). Huge congrats to you!

Learn the drive the Volkswagens. The ability to pilot a 747 will come along in due course.

That’s basically what I was taught through the writing courses I took in college. It may have been that I was being taught writing and story by English professors who were not themselves really writers. (Save for publish-or-perish articles, the once-in-a-lifetime esoteric short story in a literary magazine. There was not a single novelist on our faculty.)

So I wrote of magnificent characters doing amazing things to the delight of morally good characters, or the to the consternation or outrage of morally bad characters.

I also brought Komroff’s book and became dizzy trying to understand his spirals and his other drawings. I purchased other books on fiction writing–always, they were about short story writing. The most practical book on story writing I purchased was about writing confession stories–a field that fed my family for awhile.

But all of that story writing–well, I was pilot looking for an airplane to fly. I knew nothing about novel structure. I was taught nothing about novel structure in college.

After college, I spent some time as a special at a major university whose writing professors were among the elites of both writers and teachers. Again, I learned nothing of novel writing structure.

Then I happened to purchase Syd Field’s book on screenwriting. The light came on. “Hey,” I said to myself. “He’s talking about story structure.” In looking for my airplane, I read the Poetics, and other works. In my own life, and in my own opinion, the breakthroughs in the teaching and writing of novel structure came AFTER Syd Field’s book hit the market.

(Believe it or not, as a special student, I took a class from a professor who had been a Hollywood writer and also a best-selling novelist. He taught us nothing about novel or story structure because he really didn’t know what it was. His stories were by guess and by golly. He worked in Hollywood in that era that produced the Williams Goldmans and the other great screenwriters. But the professor could not tell us how to write novel story structure.)

When I finally DID learn story structure, I began to write novels–no, I mean honest-to-gosh novels, because story structure made EVERYTHING fall into place.

So though I have learned to drive the little cars, I am now sitting at the controls of a huge airliner, learning what happens if I press that button or push that lever. And, there have been moments when I have done something that produced pretty scary flight. But at least now I have the instruction manuals that tell how best to take off and fly the durn burn thing.

So I’ve learned that story structure DOES indeed drive everything. The right structure works, gives the hero a lot of things to do. A character must be active in the story, to accomplish the goals the structure sets up.

It’s something that’s sort of difficult to see from the driver’s seat of a Volkswagen. It’s easier to see it from the left seat of my airplane.

As a huge fan of flying metaphors relative to writing, I love this. Within that analogy, it’s interesting to note that the same “forces” that allow a Cessna to get off the ground apply no differently to a 747, though the management of the machine is more complex. Thanks for contributing this today!

I don’t have a formal education in writing, but I do have a basic canon of books that are indispensable.

Plot and Structure – James Scott Bell

Conflict and Suspense – James Scott Bell

Story – Robert McKee

Story Engineering – Larry Brooks

Story Fix – Larry Brooks

I have read many others, but these five form the core of what i use to craft a story.

That and Scrivener, too.

Brian Hoffman

Proud to be among those names on your shelf, Brain. Wishing you great success!

A new (to me) and intriguing view of character growth. Thanks for illuminating the way.

Pingback: Top Picks Thursday 11-05-2015 | The Author Chronicles