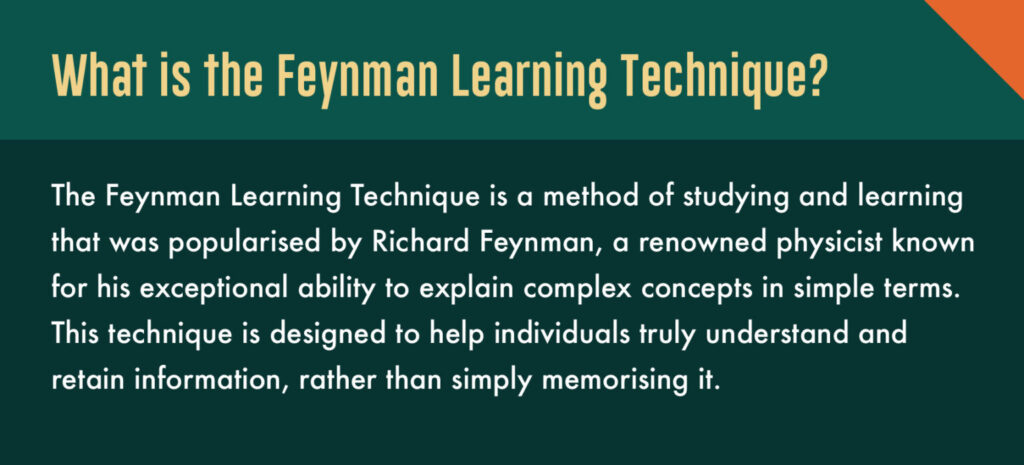

A great way to understand and retain a subject is through the Feynman Learning Technique. Regardless of topic, the technique leverages the power of teaching for better learning of timeless ideas. It’s also used for new work, like clearly understanding the plot in your story.

It’s said you don’t really know something until you can build it. It’s also said you don’t really understand a concept until you can teach it to others. This is where the Feynman Technique shines.

The Feynman Learning Technique is a proven method for learning and understanding concepts by teaching them to others, as if you were explaining the subject to a beginner such as a sixth grader. It’s designed to help learners (future teachers) truly understand and retain information, rather than simply memorizing it for a test, then swirling significant stuff down the drain of post-exam obscurity.

This learning and teaching technique is named after Richard Feynman, an American theoretical physicist who won a Nobel Prize in 1965. Mr. Feynman was nicknamed “The Great Explainer” for his phenomenal ability to understand complex subjects and break them down into simple terms and explain them in a way that a sixth grader could grasp.

Think about the plot in your current work in progress. Or take any plot in a past work. Or maybe an idea for a story you have floating in your mind. Would you, off the tip of your tongue, be able to explain it to a kid and have them immediately get what you’re about? Using the Feynman Technique might make this easier.

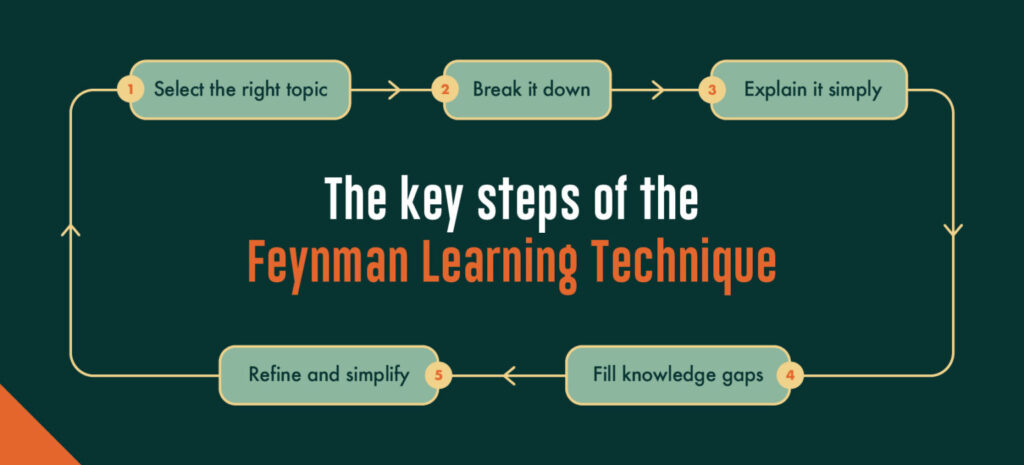

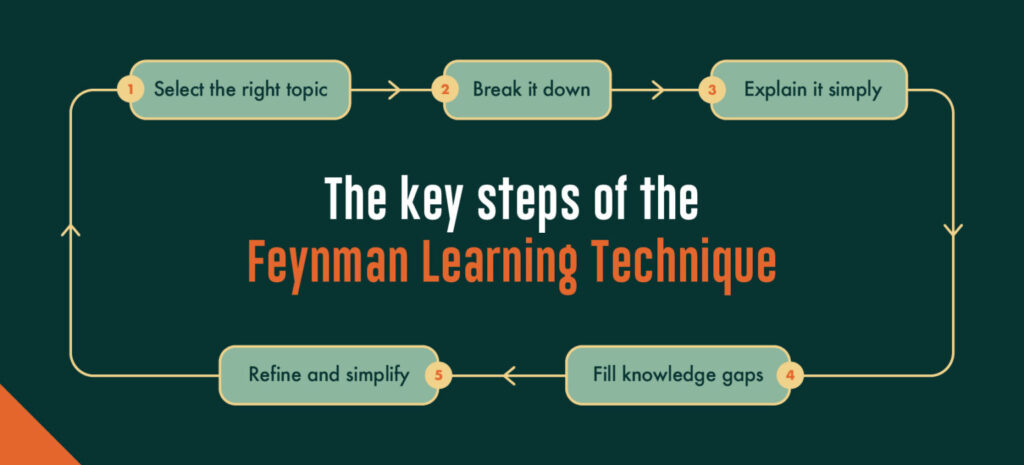

There are five key steps in Feynman. They’re actually quite simple when you think them through. In logical order, they are:

Step 1: Selecting the topic. For a story this would be genre and the general plot line.

Step 2: Breaking it down. This would be the arch, chapters, scenes, characters, key dialogue, mood, and theme.

Step 3: Explain it simply: As brief as possible, what happens to the characters.

Step 4: Fill in the knowledge gaps. What you’ve left out that’s important.

Step 5: Refine and simplify: What the bare bones is that a sixth grader would get.

The Feynman Technique goes beyond learning an existing topic. It opens a window into a different way of thinking that allows you to tear ideas apart and reconstruct them from the ground up. It also allows you to supercharge your learning from others.

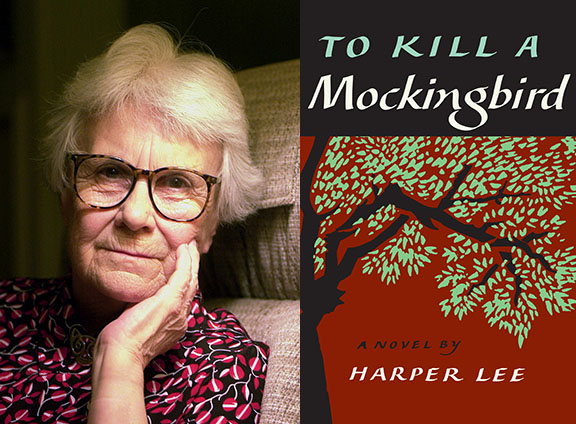

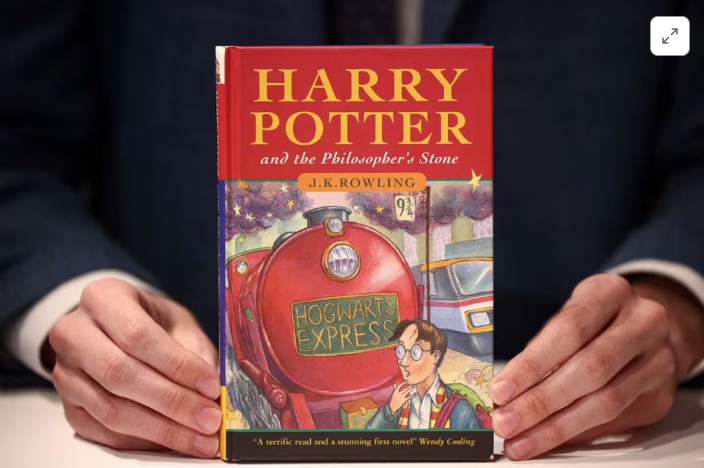

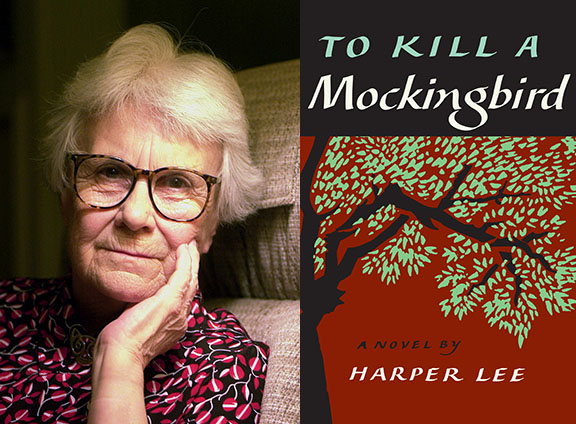

You’re probably wondering about a real-world application of the Feynman Technique. I certainly was when I first discovered this imagination and knowledge enhancement tool. So, for this exercise let’s look at using Feynman to explain the plots of four highly successful stories — The Firm by John Grisham, The Stand by Stephen King, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone by J.K. Rowling, and To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee.

I’ve read these four books, but that was quite some time ago. Today, I wouldn’t be able to concisely explain their plots to a sixth grader, and I don’t have time to reread them in order to write this blog post. So, I’ve done what I’ve done so often in the past year, and please don’t judge me harshly for it. I’ve turned to my research assistant, Chat GPT, and gave it some prompts.

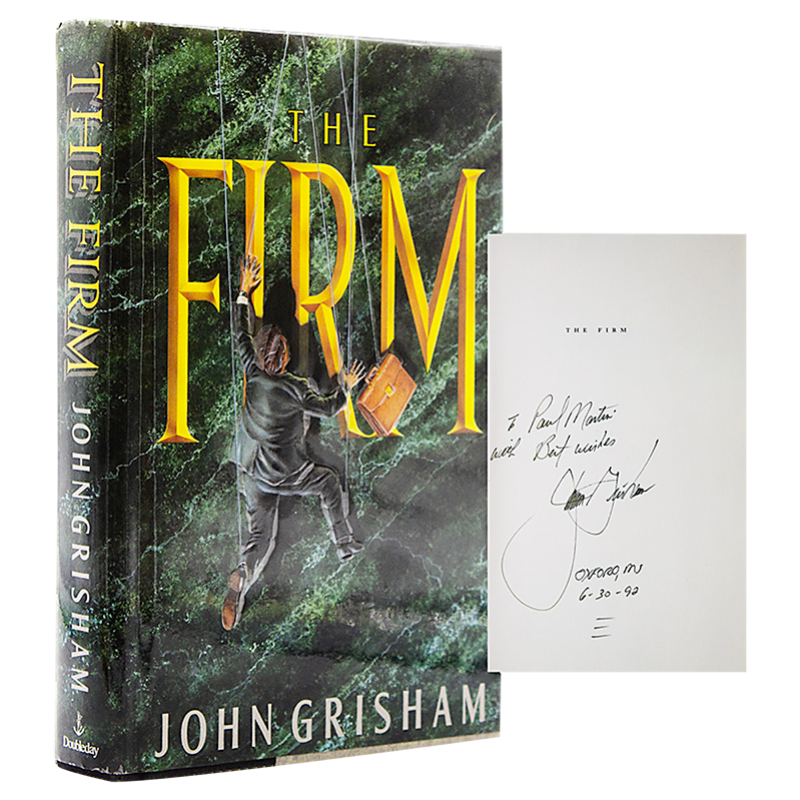

Q — Using the Feynman Learning Technique, please explain the plot of John Grisham’s book The Firm to me, assuming I’m a sixth grader.

A — Sure, let’s break down the plot of “The Firm” by John Grisham for you, imagining you’re a sixth-grader:

Meet Mitch: Okay, so there’s this guy named Mitch. He’s super smart, just finished law school, and gets a job at a fancy law firm. Imagine Mitch as the hero of our story.

Exciting Job, Shady Secrets: Mitch is excited because his new job pays a lot and seems perfect. But guess what? The law firm has some secrets. It’s doing things that aren’t so good, like working with some really bad people.

Big Problem for Mitch: Mitch finds out about these secrets, and it becomes a big problem. The FBI, like the police but for really big crimes, wants Mitch to help them catch the bad guys at the law firm. Now, Mitch has to decide what to do.

Hard Choices: Imagine Mitch feeling like he’s in a tough spot. If he helps the FBI, he could be in danger from the bad people at the law firm. But if he doesn’t help, he might be in trouble with the law.

Adventure and Danger: So, Mitch starts doing some detective work of his own, trying to gather evidence against the bad guys. It’s like a big adventure with lots of danger and excitement.

Smart Moves: Mitch is really smart, so he comes up with clever plans to outsmart the bad guys and the FBI. It’s like a game of chess where he has to think ahead to stay safe.

Happy Ending: In the end, Mitch figures everything out and helps the good guys catch the bad ones. He’s a hero, and things get better. But Mitch also learns that sometimes doing the right thing is tough.

So, that’s “The Firm” in a nutshell. Mitch, the smart lawyer, gets caught up in a tricky situation with a not-so-good law firm, but he uses his brains to make things right in the end. Pretty exciting, huh?

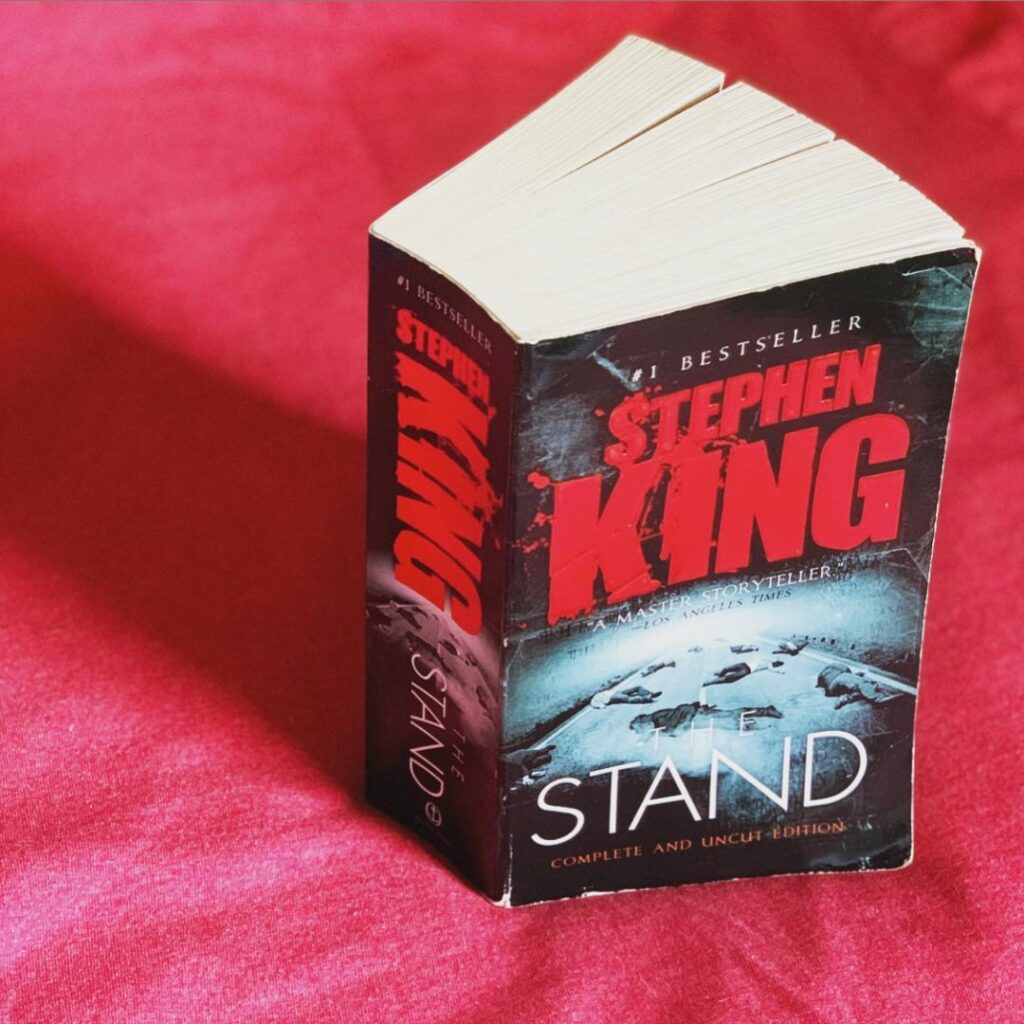

Q — Using the Feynman Learning Technique, please explain the plot of Steven King’s book The Stand to me as if I’m a sixth grader.

A — Certainly! Let’s break down the plot of Stephen King’s “The Stand” for you, imagining you’re a sixth-grader:

The World Changes: Imagine a world where something really bad happens. A super contagious sickness spreads, and a lot of people get really sick. It’s like a big sneeze, but way scarier.

Meet the Good and Bad Guys: In this world, there are good people and bad people. The good folks, like a guy named Stu and a lady named Fran, try to survive and help others. But there’s also a really mean guy named Randall Flagg who wants to take over.

The Journey Begins: Stu, Fran, and some other good people go on a journey. They’re like a team of superheroes trying to find a safe place where they can start over and be safe from the sickness and the mean Randall Flagg.

Superpowers and Challenges: Along the way, some people discover they have special powers. It’s like having superhero abilities. They face challenges, like finding food and avoiding the mean guys who want to make trouble.

The Big Showdown: Eventually, the good guys and the bad guys have a big showdown. It’s like the final battle between superheroes and villains. Who will win?

Starting Over: After all the excitement, the story shows what happens when the good guys try to build a new, better world. It’s like hitting the reset button after a big adventure.

Happy and Sad Moments: There are happy moments when the good guys succeed, but also sad moments when they lose friends. It’s like a rollercoaster of emotions.

The End and New Beginnings: In the end, the story wraps up, and you see how the characters’ lives change. It’s like finishing a really good book and feeling both satisfied and a bit sad that it’s over.

So, “The Stand” is like an epic adventure with good guys, bad guys, superpowers, and a lot of ups and downs. It’s about survival, friendship, and starting fresh in a world that’s been turned upside down. Pretty cool, right?

Q — Using the Feynman Learning Technique, please explain the plot of J K Rowling’s book Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone as if I were a sixth grader.

A — Absolutely! Let’s break down the plot of J.K. Rowling’s “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone” for you, as if you were a sixth-grader:

The Ordinary Kid: Meet Harry Potter, a regular kid who lives with his not-so-nice aunt, uncle, and cousin. He doesn’t know he’s special yet.

Mysterious Letters: One day, Harry starts getting these super mysterious letters, but his family won’t let him read them. It’s like a big secret.

Hagrid and Hogwarts: A giant man named Hagrid shows up on Harry’s birthday and tells him he’s a wizard! Hagrid takes Harry to a magical school called Hogwarts, where he’ll learn all about magic and make new friends.

Magical Classes and Friends: At Hogwarts, Harry takes cool classes like Potions, Charms, and Flying on broomsticks. He becomes friends with Ron and Hermione, and together they have all sorts of magical adventures.

The Philosopher’s Stone: There’s this super special thing called the Philosopher’s Stone that can make you live forever. Harry, Ron, and Hermione find out that someone is trying to steal it, and they want to stop them.

House Points and Quidditch: At Hogwarts, students earn points for their houses by doing good things and lose them for breaking rules. Harry also plays Quidditch, a magical sport on broomsticks, and it’s a big deal.

Facing Danger: Harry discovers that the bad guy who wants the Sorcerer’s Stone is really dangerous. With Ron and Hermione, he faces challenges and puzzles to reach the stone before it falls into the wrong hands.

The Final Confrontation: In the end, Harry faces the bad guy, who’s trying to use the stone for something very dark. It’s like the big boss battle in a video game.

Victory and Celebration: Harry and his friends manage to save the day! There’s a big celebration at Hogwarts, and they earn a bunch of house points for being heroes.

Back to Normal… Almost: After all the excitement, Harry goes back to live with his aunt and uncle for the summer, but now he knows he’s part of this amazing magical world.

So, “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone” is about an ordinary kid discovering he’s a wizard, making friends, learning magic at Hogwarts, and facing danger to protect something really important. It’s a magical adventure full of friendship and bravery! Cool, right?

Q — Using the Feynman Learning Technique, please explain the plot of Harper Lee’s book titled To Kill a Mockingbird as if I were a sixth grader.

A — Certainly! Let’s break down the plot of Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” for you, imagining you’re a sixth-grader:

Meet Scout and Jem: The story is about a girl named Scout and her brother Jem. They live in a small town called Maycomb in the southern United States during the 1930s.

Mystery Neighbor Boo Radley: There’s a mysterious neighbor named Boo Radley who never comes out of his house. Scout, Jem, and their friend Dill are curious about Boo and make up stories about him.

Dad is a Lawyer: Scout and Jem’s dad, Atticus Finch, is a lawyer. He’s a really good guy and tries to teach his kids about fairness and kindness.

Tom Robinson’s Trial: Atticus defends a man named Tom Robinson, who is unfairly accused of a crime he didn’t commit. The trial is a big deal in the town, and it shows how people can be unfair because of prejudice.

Learning about Racism: As Scout and Jem grow up, they learn about racism and the unfair treatment of people based on the color of their skin. It’s a tough lesson for them.

Boo Radley’s Surprise: Boo Radley, the mysterious neighbor, turns out to be kind and helps Scout and Jem when they’re in trouble. It’s a surprise because he’s not what they expected.

The Mockingbird Lesson :Atticus tells Scout and Jem that it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird because they are harmless and bring joy. The mockingbird becomes a symbol for innocent and good-hearted people.

Understanding Empathy: Through the experiences with Boo Radley and the trial, Scout and Jem learn about empathy—putting themselves in others’ shoes to understand their feelings.

Growing Up and Lessons Learned: The story is about growing up, facing challenges, and learning important life lessons. Scout and Jem become wiser and more understanding as they go through these experiences.

Final Lessons of Justice: The book teaches about justice, fairness, and the importance of standing up for what’s right, even when it’s hard.

So, “To Kill a Mockingbird” is a story about two kids growing up in the 1930s South, learning about racism, empathy, and justice, and discovering that sometimes people aren’t what they seem. It’s a powerful story with important lessons about understanding and standing up for what’s right. Cool, huh?

Monroeville, Alabama – August 31, 2001 – A photo of the author Harper Lee, who wrote “To Kill a Mockingbird.” Photo is at the house where she spends half the year. Monroeville is where Lee was born and raised. Tribune Photo by Terrence Antonio James.

Kill Zoners — What do you think of the Feynman Learning Technique? Have you ever used it? Do you see the value in plotting with it or at least clarifying your plot? And who is brave enough to take one of their stories—old, current, or forthcoming—and write out an explanation of the plot to a sixth grader?

Edmund Burke, the eighteenth century member of Parliament known for his rousing speeches, regarded every word in a sentence as “the feet upon which the sentence walks.” He said that to alter a word—exchange it for a shorter or longer one, or give it a different position—would change the whole course of the sentence.

Edmund Burke, the eighteenth century member of Parliament known for his rousing speeches, regarded every word in a sentence as “the feet upon which the sentence walks.” He said that to alter a word—exchange it for a shorter or longer one, or give it a different position—would change the whole course of the sentence.