By SUE COLETTA

An interesting discussion arose while working on copy edits for Pretty Evil New England. The conversation dealt with using block quotes—when, where, why, and how I used them in the (nonfiction) manuscript.

An interesting discussion arose while working on copy edits for Pretty Evil New England. The conversation dealt with using block quotes—when, where, why, and how I used them in the (nonfiction) manuscript.

If at all possible, I tend to use quoted material as dialogue to create scenes. But there were times where I chose to block quote the text instead. For example, if the quote was mainly backstory and not part of the actual scene but still important for the reader to understand, then I used block quotes. You’ll see what I mean in one of the examples below.

Block quotes can’t be avoided at times. They can even enhance the scene, thereby adding to the overall reading experience. In fiction, two examples of where to use block quotes would be a diary entry or a note/letter/message. Please excuse my using one of my thrillers; it’s easier than searching through a gazillion books on my Kindle.

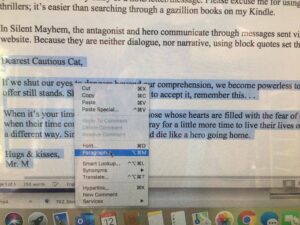

In Silent Mayhem, the antagonist and hero communicate through an Onion site (untraceable) on the deep web. Because these messages are neither dialogue, nor narrative, using block quotes set them apart.

Example:

Dearest Cautious Cat,

If we shut our eyes to dangers beyond our comprehension, we become powerless to fight. My offer still stands. Should you choose not to accept it, remember this . . .

When it’s your time to die, be not like those whose hearts are filled with the fear of death, so that when their time comes, they weep and pray for a little more time to live their lives over again in a different way. Sing your death song and die like a hero going home.

Hugs & kisses,

Mr. M

Block quotes also break up the text and enhance white space. We’ve discussed white space many times on TKZ. For more on why white space is a good thing, check out this post or this one.

BLOCK QUOTES IN WORD

To include block quotes in Word, highlight the text and right click. This screen will pop up…

Choose “paragraph” and this screen will pop up…

Choose “paragraph” and this screen will pop up…

Reset your left margin to .5 and click OK. Leave the right margin alone.

Quick note about margins.

A good rule of thumb for block quotes is to not indent the first paragraph. If your passage contains more than one paragraph, check with the publisher. Most supply a style guide. For instance, my thriller publisher keeps all paragraphs justified. My true crime publisher prefers that the first paragraph be justified and subsequent paragraphs be indented.

To do that, the easiest thing is to click “Special” then “first line” (as indicated in pic below) and set it to .25. Then simply backspace to erase the indent on the first paragraph.

If you’re self-publishing, then obviously it’s your call on whether to indent or not to indent subsequent paragraphs.

BLOGGING BLOCK QUOTE

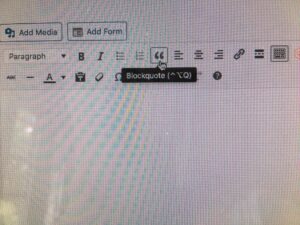

Bloggers who include passages from a resource, whether that be a book or wording from a reputable source, use block quotes to signal the reader that the passage is a direct quote (most commonly, all justified margins). You could style the post in Word, then copy/paste, but sometimes the style doesn’t paste over. Simple fix. Highlight the text and click this symbol…

And that’s it. Easy peasy, right?

And that’s it. Easy peasy, right?

ELLIPSIS

An ellipsis consists of either three or four dots. A single dot is called an ellipsis point. Some writers may find using ellipses a little tricky, but once you know the definitions of where, why, and how to use them, determining the right ellipses is fairly straightforward.

According to the Chicago Manual of Style, never use ellipses at the beginning or end of a block quote. CMOS also recommends using equal spacing between dots. Some style guides say to use three equally spaced periods rather than creating an ellipsis in Word, which you can do by pressing CTRL + ALT + Period. Always go by the style guide furnished by the publisher (or editor, if self-publishing).

WHERE AND WHY TO USE ELLIPSES

There are many reasons why you might want to use an ellipsis. An ellipsis can indicate omitted words within the middle of a quote, or faltering dialogue, or an unfinished sentence or thought where the speaker’s words trail off.

For faltering dialogue, you have two choices, depending on your style guide.

Style #1: Equally spaced dots with one space before and after ellipsis.

Style #2: Unspaced dots with one space before and after ellipsis.

Example #1 (uses three periods): “I . . . I . . . would never break the law.”

Example #2 (uses ellipsis created with Word shortcut): “I … I … would never break the law.”

For words that trail off, insert punctuation at end of ellipses. If the dialogue continues to another sentence, leave a space.

Example #1: “Why would he . . .? I mean, I can’t believe he got caught with that bimbo.”

Alternate style (Word shortcut): “Why would he …? I mean, I can’t believe he got caught with that bimbo.”

Example #2: “My weight? I’m about one hundred and . . . So, how ’bout them Bears. Did you watch the game?”

Alternate style (Word shortcut): “My weight? I’m about one hundred and … So, how ’bout them Bears. Did you watch the game?”

THREE DOTS VERSE FOUR

Here’s where some writers may find ellipses a little tricky.

Sometimes we need to omit words from the end of one sentence but still continue the quoted passage. This type of ellipsis is called a terminal ellipsis. In this instance, the CMOS recommends using four dots, or periods. The fourth dot indicates the period at the end of the sentence that we haven’t quoted in its entirety. By including that fourth dot it lets the reader know that the quotation borrows from more than one sentence of the original text.

Example from Pretty Evil New England:

Then I made up my mind to kill Mrs. Gordon. Poor thing, she was grieving herself to death over her sickly child. So life wasn’t worth living anyway. I was sorry, though, for the poor, unfortunate child, Genevieve. I love the little one very much. . . . I thought with Mrs. Gordon out of the way I could be a mother to her child and get [her husband] Harry Gordon to marry me.

Notice how I didn’t omit any necessary words? That’s key. We have a responsibility to other writers—in this case, the female serial killer—to not mislead the reader by leaving out words that change the meaning of the quote.

Three most important takeaways for ellipses in dialogue.

- Avoid ellipses overload—too many can diminish their impact.

- Reserve ellipses for middle and end of dialogue. If the character fumbles around to spit out their first word, use a body cue or other description instead.

- Maintain consistent ellipses spacing throughout the manuscript.

Now, like most things in writing, there are exceptions to these rules. Always follow the publisher or editor’s recommendations. If you don’t have any recommendations to follow, feel free to use this post as a guide.

For discussion: Do you use block quotes in your writing? If so, why did you choose to do that? Care to share one of the exceptions to any of these guidelines?