Reader Friday: Emotional Scenes

When you’re writing an emotionally draining (or sexy, or sad, etc.) scene, how do you get in the mood?

When you’re writing an emotionally draining (or sexy, or sad, etc.) scene, how do you get in the mood?

Image by Annalise Batista from Pixabay

Reader Friday: Emotional Scenes

When you’re writing an emotionally draining (or sexy, or sad, etc.) scene, how do you get in the mood?

When you’re writing an emotionally draining (or sexy, or sad, etc.) scene, how do you get in the mood?

Image by Annalise Batista from Pixabay

by Debbie Burke

Crime writers have—shall we say?—unusual research needs. We often joke that law enforcement could knock on our doors at any moment because of suspicious internet searches.

Recently, I ran across a site called Murderpedia. It claims to be the largest free database of serial killers and mass murderers around the world. It lists more than 5800 male murderers and more than 1000 female murderers going back hundreds of years in history.

It’s indexed alphabetically by both the killer’s name and by the country where the murder(s) occurred. Each entry chronicles the crime(s), method of death, and ultimate disposition of the case–hanging, firing squad, guillotine, life in prison without parole, etc. Additionally, there are photos, artists’ renderings, and illustrations to go with some stories.

At random, I chose a link to Bridget Durgan, an Irish housekeeper who was so horribly mistreated by her various employers that she vowed to kill them if she ever had the chance. In New Jersey in February, 1867, an opportunity arose. Durgan stabbed and clubbed her employer, Mrs. Mary Ellen Coriel, to death then set the Coriel house on fire, blaming the crime on robbers. Nobody believed her and she was found guilty at trial.

While in prison awaiting execution, Durgan revealed her sad life to the Reverend Mr. Brendan who published her story as a cautionary tale. The illustrated pamphlet was also likely sold to spectators at Durgan’s hanging.

Lurid pen and ink drawings show the mortally wounded Coriel still alive, lying on the floor near her baby, Mamey, and the wild-eyed Durgan standing over them. Durgan reportedly said she allowed Coriel to kiss her child goodbye before finishing her off.

Durgan was hanged in August, 1867.

After perusing the Murderpedia site for an hour (or three!), I was struck by the immense amount of work that had gone into researching and cataloging thousands of cases. Then I noticed the last update was in 2017.

What had happened to Murderpedia?

Down the rabbit hole I tumbled.

I found out that the curator/director was a Spanish criminologist and author named Juan Ignacio Blanco whose own story is nearly as strange as the cases he chronicled. In 1992, he investigated the triple murder of three teenage girls, known as the Alcasser case. He believed two men accused of the crimes were scapegoats who’d been set up by wealthy, politically-connected, Spanish power brokers to cover their own guilt and to divert attention from their other crimes, including pedophilia.

Blanco was branded a conspiracy theorist.

After he published a book about his findings, he was convicted of insulting and slandering officials in charge of investigating the case and served time in prison. His book was judicially seized in 1998 because it included autopsy photos of one victim without her family’s consent. Accusations swirled that Blanco and the father of another victim in the case had set up and operated a foundation that resulted in hefty profits to both of them.

Shortly before Blanco’s death from cancer at age 63, he appeared in a 2019 Netflix series that reexamined the Alcasser Murders.

Was Juan Ignacio Blanco a greedy opportunist who capitalized on a terrible tragedy or a courageous crusader against corruption seeking truth and justice?

Whatever he was, he left behind the vast library of Murderpedia, crammed with painstaking research that’s a fascinating resource for crime writers.

~~~

TKZers: What’s your favorite crime research rabbit hole?

~~~

If Hurricane Irma doesn’t kill Tawny Lindholm, a shady sports dealer will when she becomes the bargaining chip in a high-stakes gamble. The winner lives, the loser dies.

Debbie Burke’s new thriller, Dead Man’s Bluff is now on sale at the introductory price of $.99. Here’s the link.

What’s Up?

by Terry Odell

Image by Andrew Martin from Pixabay

I’ve been going through my manuscript, getting it ready to send to my editor. I’ve run checks on overused words and phrases using a program called SmartEdit—which, as always, finds a new one every time. This time it was “about.” But there’s another word I check for.

My high school Latin teacher used to share his opinions on unnecessary words and redundancies. Saying “From its earliest beginnings to it final completion” pushed his buttons. He complained that the word “up” was overused, and often unnecessary. Why say ‘face up to a situation’? To which class clown Leon replied, “So what’s the guy robbing a bank supposed to do? Walk up to the teller and say “This is a stick?”

Leon’s wit notwithstanding, up is a word I run checks on, because it seems to slip off the fingertips without conscious thought—over 300 times in this manuscript—and often can be dispensed with. Here’s an essay we used to use when we were training tutors for the Adult Literacy League in Orlando. I thought I’d share it today.

What’s Up With Up?

“We’ve got a two-letter word we use constantly that may have more meanings than any other. The word is up.

“It is easy to understand up, meaning toward the sky or toward the top of a list. But when we waken, why do we wake up? At a meeting, why does a topic come up? And why are participants said to speak up? Why are officers up for election? And why is it up to the secretary to write up a report?

“The little word is really not needed, but we use it anyway. We brighten up a room, light up a cigar, polish up the silver, lock up the house and fix up the old car.

“At other times, it has special meanings. People stir up trouble, line up for tickets, work up an appetite, think up excuses and get tied up in traffic.

“To be dressed is one thing, but to be dressed up is special. It may be confusing, but a drain must be opened up because it is stopped up.

“We open up a store in the morning, and close it up in the evening. We seem to be all mixed up about up.

“In order to be up on the proper use of up, look up the word in the dictionary. In one desk-sized dictionary, up takes up half a column; and the listed definitions add up to about 40.

“If you are up to it, you might try building up a list of the many ways in which up is used. It may take up a lot of your time, but if you don’t give up, you may wind up with a thousand.”

Frank S. Endicott

Do you have any crutch words that appear on the page all too frequently?

By Debbie Burke

Gruesome Warning – This post contains graphic details of a horrific bombing that killed three people, including a two-year-old child.

Dogs are helpmates that do most anything their people ask of them…including jobs that no one, human or animal, should have to do…like finding body parts after an explosion.

Kerrie Garges has spent nine years as a volunteer dog handler for Alpha K-9 Search and Rescue (SAR) in Chalfont, PA, population 4,000. Until the COVID 19 crisis, her day job was teaching environmental education at Peace Valley Park Nature Center in Bucks County.

She fell into SAR “by accident” as a dog-loving empty-nester looking for a way to help her community. At a training exercise with her then-new Labrador, Ace, the instructor observed that Ace showed an aptitude for “air scent” (tracking smells through the air rather than on the ground) and invited her to join SAR.

Ace, age 10, is now retired but Kerrie continues to train and work with two more Labs: Luna, age 5, is Trailing Certified and is training for Human Remains Detection (HRD). She practically yanks Kerrie’s arm out of the socket when she’s on the hunt.

Gauge is Kerrie’s rambunctious one-year-old about which she jokes, “Just shoot me in the head!” He’s gradually growing out of puppyhood as he trains for certification in Live Find and HRD. She says, “When Gauge has his vest on, he knows he’s working.”

Most searches Kerrie has worked involve people with dementia who’ve walked away from home and gotten lost.

A completely different—and hideous—search would test the mettle of Kerrie and other dog handlers who were called in by the Lehigh County assistant coroner to work a murder-suicide crime scene in 2018.

On September 29, at 9:30 p.m., an explosion shook the Center City neighborhood in Allentown, PA. The cause was initially believed to be a car fire. First responders instead found that a powerful homemade bomb had detonated inside a car, killing three people and damaging surrounding buildings and homes for blocks.

Investigation determined the bomb had been built by Jacob G. Schmoyer, 26, with the express intention of killing himself, his two-year-old son Jonathan (“JJ”), and a casual friend David Hallman, 66, to whom Schmoyer owed $150. Before the explosion, Schmoyer had sent letters to family members and the Allentown Police Department in which he expressed anger as well as concern that JJ might have autism.

That night, Schmoyer lured Hallman into his Nissan Altima, where he and JJ were already sitting, with the promise to pay back the money.

Instead, he detonated the bomb which killed the three occupants, shredded the car, and cast debris and body parts over a five-block area.

Following the initial investigation, Lehigh County’s assistant coroner requested help from Alpha K-9 SAR to locate human remains amid the rubble. Kerrie said, “We’re a small group without a lot of resources, so we were honored to be called for this important mission.”

For this job, Kerrie did not bring her own dogs, which are still in training. Dogs must be tested and certified by National Association of Search and Rescue (NASAR) to perform real-world work. Kerrie acted as a support person to handlers and three dogs that are certified in HRD.

On the morning of October 2, the Alpha K-9 SAR volunteers arrived in Allentown, an hour’s drive from Chalfont. An eight-block area had been cordoned off. They were escorted past crime scene tape into destruction that Kerrie described as “a war zone.”

Following the blast, residents of surrounding blocks had been evacuated. Broken glass, tree limbs, chunks of buildings, and hazardous debris were everywhere, causing Kerrie concern because the dogs didn’t have protective footwear. Coroner’s office personnel offered to adapt the knee-high protective coverings that humans wore to fit the K-9s. After discussion, the handlers decided that, since the dogs weren’t accustomed to working with booties, wearing them might be too distracting. They closely monitored the dogs’ paws but fortunately there were no injuries.

Kerrie expressed “new respect for disaster dogs” working under similar dangerous conditions.

The day was hot and coroner’s office personnel made sure the volunteers and dogs had extra water and could cool off in air-conditioned vehicles when necessary.

The densely-populated, inner-city area of Allentown contrasted sharply with the suburban schools, parks, and rural locations where the Chalmont team normally worked. Older houses were crowded together, many converted to multi-family apartments. Narrow passageways called “bakers alleys” separated the buildings.

Adjacent to the cordoned-off crime scene area, Kerrie smelled meth cooking. Although law enforcement was nearby, she was startled to see bystanders carrying on drug deals and smoking marijuana. Those scents, mingled with dust and smoke caused by the explosion and fire, created a confusing mix for the dogs to sort out. She said, “It took about twenty minutes for them to get acclimated to the scene” in order to focus on finding human remains.

The coroner’s office created a map of the areas to be searched. Each dog team was assigned a different sector. Coroner’s assistants accompanied the teams, taking photos of pieces of burned flesh as they were found. The evidence was then “bagged and tagged” and taken to the crime lab.

One dog kept wanting to climb over a stone wall to get into a particular house. Inside, the searchers found shattered windows and furniture overturned by the explosion. A TV was still on, forgotten when residents quickly evacuated. The team also found a frightened puppy that had been left behind, tied up with no food or water. “That bothered me a lot,” Kerry said. Officers carried the pup to safety.

As they proceeded through the area, the dogs kept raising their heads, looking up, which mystified the handlers who couldn’t see anything. At last, they discovered “a giant flap of flesh” stuck high in the gutter of a four-story building, a horrifying indication of the power of the blast.

“We [searchers] felt disgust,” Kerrie said. “Not stomach-churning kind of disgust but rather mental and emotional disgust that the man had killed his little boy and his friend and caused all these poor people to be ousted from their homes and businesses.”

The search lasted four hours and located human remains as far away as five blocks from where the bomb had exploded. Each dog found at least three pieces, the largest being the flap of flesh in the gutter. The smallest was a charcoal-colored, wafer-thin piece of burned flesh the size of a quarter. Kerrie recalled, “I’d watched a documentary about [the atomic bomb at] Hiroshima and that’s the first thing I thought of when I saw this piece.”

Even veteran law enforcement officers were shaken by the devastation and the senseless death of a toddler. Counselors were offered to those struggling with what they’d seen.

When I asked Kerrie how the dogs reacted to such horrors, she said, “Dogs consider it a job.” They were just happy to please their humans.

The handlers had a hard time expressing their emotions about the gruesome mission but they all felt pride in the dogs and the teamwork of SAR. “The memory always stays with you. You never forget,” Kerrie said. “But this is what we train for every week. We want to utilize the skills we’ve learned. We almost felt rejuvenated, as well as proud and humbled to be called to do this important work.”

Investigations continued for more than a year by local police and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, which determined Schmoyer acted alone and the explosion was not related to terrorist activity.

No amount of investigation will ever explain why Schmoyer intentionally killed his own child and a friend who’d been decent enough to lend him money.

SAR volunteers perform difficult jobs few people could endure. They can be summoned in the middle of the night or during miserable weather. They finance training out of their own pockets. They work without pay. They’re proud of the job they do and the strong bond they develop with their dogs.

Crime dogs perform other functions, too. One recent evening, Kerrie felt particularly blue because of current events in the world. Her youngest dog, the often-exuberant Gauge, came from two rooms away and climbed on the couch beside her. He laid one paw on her shoulder and snuggled his face in her neck. “He made me feel better,” Kerry said. “He made me smile.”

That may be a dog’s most important job.

~~~

TKZers: Have you been involved in SAR work? Have you been in a situation where search dogs were deployed?

~~~

A big shout-out of appreciation and gratitude to TKZ regular reader Brian Hoffman who designed this beautiful new cover for Dead Man’s Bluff.

Brian, you’re the best!

Today is launch day for Debbie Burke’s new thriller, Dead Man’s Bluff, on sale for only $.99 for a limited time at this link.

Please welcome Steven Ramirez to TKZ!

If, as Stephen King likes to say, the road to hell is paved with adverbs, then finishing a novel is paved with mouse traps; and here you are trying to get across that minefield in your bare feet.

As writers, we tend to get distracted—a lot. Thanks, Netflix. And then, there’s life. How many of you have said, “If only I could focus exclusively on my writing, I’d finish this damn book, by cracky.” I know I have. Repeatedly over the years, much to the irritation of my long-suffering wife.

Then, a little thing called COVID-19 happened. We were told we had to shelter in place. Sure, there was still Netflix and Amazon Prime to distract us, but we couldn’t go anywhere. What’s a writer to do? Well, like the wily poker player whose bluff was called, I decided to shut up and write. And guess what, I finished the damn book.

Pantsers Are People, Too

I’m a pantser by trade. That means I don’t have a clue where I’m heading when I begin a new book. That’s not entirely true. I do know where I would like to end up, but I haven’t worked out the details. I have a main character in mind, of course. And I’m pretty clear on the conflict arising between the MC’s goal and the thing standing in the way. Other than that, I’m free as a bird when it comes to the plot. I suspect that some plotters look at pantsers as undisciplined children with uncombed hair and sticky fingers. My image of a plotter is a person who dresses impeccably and has an English accent. Borrowing from the wonderfully insane film Galaxy Quest, plotters are Alexander Dane, while pantsers are Jason Nesmith.

The book in question is the third in my supernatural suspense series, Sarah Greene Mysteries. My main character sees ghosts, which tends to get her into serious trouble. Over the course of the three novels, Sarah goes from discovering a mirror that holds the spirit of a dead girl to the entire town pretty much erupting into flames.

Now, as a card-carrying pantser, I had no idea how I was going to go from a murder mystery to Armageddon. I had to trust that the characters would get me to my destination. Spoiler alert—going about crafting a novel this way requires you to rewrite. Often. That’s the downside. The upside is, there are lots of opportunities for discovery. And then, there is what I like to call the happy accident, which in my opinion, is a gift from heaven and makes for a better story.

Brain Teasers

I’m no psychologist, but I suspect that somewhere deep in the nooks and crannies of my brain is THE STORY. By the way, can you even have a nook without a cranny? Just wondering. Anyway, like a sculptor working a block of marble, my job is to remove everything that isn’t the story. I’m pretty sure this is easier for plotters. I’m guessing they sit down and chisel out the plot until it operates like a Swiss watch. That’s just not for me.

“So, what about writer’s block, Mr. Too-Busy-To-Be-A-Real-Writer?” you say. Well, I don’t believe in it. Sure, there are times when we get stuck. But guess what. Even when the words are not flowing onto the page, your brain is working on the story. Maybe not consciously. But, trust me, you’re still writing. My belief is, once we can accept that not all writing translates into words on paper, the more relaxed we become. I was going to say happy, but whoever heard of a happy writer, am I right?

When I get stuck, I set aside the manuscript for a few days and either work on something else (and you should always have something else to work on) or watch television. While my conscious mind is laughing its butt off at The Good Place, my unconscious is free to work. In fact, my psyche—whose name is Stan, by the way—was probably praying I would stop looking over his shoulder and vacate the room so he could get back to creating. Stan does tend to get irritable. But I don’t blame him. I mean, I’m no picnic. Ask my wife.

Survey Says

So, where does all this leave us in terms of writing while sheltering in place? Well, when things happen that are beyond our control, we are presented with choices. I suspect that many of you out there took a look at the situation and, like me, wrote like the wind these past few months. Maybe you didn’t finish your book, but I’ll bet you made significant progress.

But what do we do when life returns, more or less, to normal? With luck, we’ve developed the discipline to carve out time each day to write. And that, my friends, is a happy accident.

TKZers: As writers, what are some of the ways you have taken advantage of these pandemic times?

Steven Ramirez is a 2019 Best Indie Book Award (BIBA) winner and a 32nd Annual Benjamin Franklin Award Silver Winner for The Girl in the Mirror, the first novel in the supernatural suspense series Sarah Greene Mysteries. A former screenwriter, he also wrote the acclaimed horror thriller series Tell Me When I’m Dead and Come As You Are, a horror collection. Steven lives in Los Angeles.

Steven Ramirez is a 2019 Best Indie Book Award (BIBA) winner and a 32nd Annual Benjamin Franklin Award Silver Winner for The Girl in the Mirror, the first novel in the supernatural suspense series Sarah Greene Mysteries. A former screenwriter, he also wrote the acclaimed horror thriller series Tell Me When I’m Dead and Come As You Are, a horror collection. Steven lives in Los Angeles.

The Girl in the Mirror: A Sarah Greene Supernatural Mystery

The Girl in the Mirror: A Sarah Greene Supernatural Mystery

While renovating an old house, Sarah Greene finds a mirror holding a dead girl’s spirit. As she explores the house’s secrets, Sarah awakens dangerous dark forces that could harm her.

Available now at Amazon.

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

In the comments to last Tuesday’s post, Kris asked me about the series of pulp-style stories I’m doing for my Patreon community. It doesn’t take much prompting to get a writer to talk about his work, now does it? So here I go.

My parents were friends with one of the most prolific pulp writers of his day, W. T. Ballard (who also had several pseudonyms). I was too young to realize how cool that was. I wish I’d been aware enough to ask him some intelligent questions about writing! (I’ve blogged about Ballard before.) Fortunately, I was the recipient of many of his paperback books and a collection of his stories for Black Mask about a Hollywood troubleshooter named Bill Lennox. Lennox was like a PI, but did his work for a studio. I thought that was a nice departure from pure detective.

So I decided to create a troubleshooter of my own. The first thing I did was write up a backstory for him:

WILLIAM “WILD BILL” ARMBREWSTER was born in 1899 in Cleveland, Ohio. He grew up on a farm and had a troubled relationship with his father, which led to Armbrewster dropping out of high school and riding the rails as a hobo. He was nabbed by yard bulls in Chicago in 1917 and given a choice: go to jail or join the Marines. He chose the Marines and saw action in France during World War I, most notably at the Battle of Belleau Wood, for which he won the Silver Star. After the war he took up residence in Los Angeles and drove a delivery van for the Broadway Department Store. At night he worked on stories for the pulp magazines, gathering a trunk full of rejection letters.

In 1923 a chance meeting with Dashiell Hammett in a Hollywood haberdashery led to a lifelong friendship between the two. Hammett asked to see one of Armbrewster’s stories, liked it, and personally recommended it to George W. Sutton, editor of Black Mask. The story, for which Armbrewster received $15, was “Murder in the Yard.” After that Armbrewster became a staple of the pulps and was never out print again. Between 1923 and 1940 he averaged a million words a year.

In 1941, after the outbreak of World War II, Armbrewster tried to re-enlist but was turned down due to his age. Instead he went to work for National-Consolidated Pictures, writing short films to inspire the troops. When one of the studio’s young stars was the victim of blackmail, Armbrewster tracked down the perpetrator and dragged him to the Hollywood Police Station. Morton Milder, head of the studio, immediately put Armbrewster on retainer as a troubleshooter.

Known as the man with the red-hot typewriter, Armbrewster wrote many of his stories at a corner table at Musso & Frank Grill in Hollywood. He was granted this favor by the owners, for reasons that remain mysterious to this day (some Armbrewster scholars believe he rescued the daughter of one of the owners from a sexual assault under the 3d Street bridge).

He Lives at the Alto-Nido apartment building, 1851 N. Ivar Avenue, Hollywood.

What is it that I love about pulp writing? Part of it is what Kris called “the streamlined locomotive style.” These stories move. There’s no time for fluff or meandering. Pulp stories were entertainments for people who needed some good old-fashioned escapism from time to time. (That hasn’t change, has it?)

There was also a nobility to the best pulp characters. They had a professional code. Even the most cynical of the lot, Sam Spade, throws over the woman he loves because, “When a man’s partner is killed he’s supposed to do something about it. It doesn’t make any difference what you thought of him. He was your partner and you’re supposed to do something about it.”

I have set my Armbrewster stories in post-war Los Angeles. What a noir town it was then, full of sunlight and shadow, dreamers and drifters, cops and conmen. And, of course, Hollywood.

I’ve now done four Armbrewster stories (which run between 7k-10k words). The fifth is due to be published soon. They aren’t published anywhere but on Patreon, so if you’d like read them you can jump aboard my fiction train for just a couple of berries ($2 in pulp lingo). Go here to find out more.

And thank you, Kris, for asking.

Is there a particular style of writing you warm to? What books or authors do you turn to for pure escapism?

Reader Friday: Characters

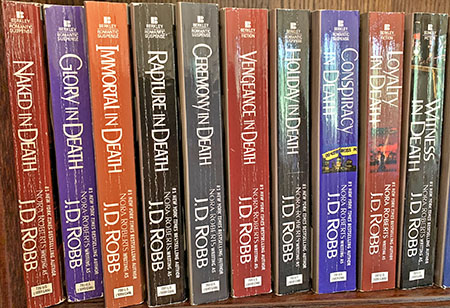

JD Robb has just published her 50th “In Death” book. The cast of characters has grown over time, but her two main characters, Eve and Roarke, have anchored every book. Other authors write multiple series featuring different characters, often those who have played secondary roles in previous books.

JD Robb has just published her 50th “In Death” book. The cast of characters has grown over time, but her two main characters, Eve and Roarke, have anchored every book. Other authors write multiple series featuring different characters, often those who have played secondary roles in previous books.

If you’re writing a series, do you get tired of the characters, or are they old friends? For recurring characters, how do you keep them fresh?

Murder. It’s forever been the stuff of books, movies, poems and plays. Everyone from Shakespeare to Agatha Christie told foul-play murder stories. That’s because, for gruesome reasons, murder cases fascinate people.

I think murder is the great taboo. It’s also the great fear of most people except, maybe, for public speaking. Jerry Seinfeld quipped, “At a funeral, the majority of people would rather be in the casket than giving the eulogy.”

Yes, murder is the ultimate crime. In mystery books and Netflix shows, murder cases are solved and neatly wrapped up in the end. This leaves the reader or audience with the satisfaction of knowing who done it and probably why.

Yes, murder is the ultimate crime. In mystery books and Netflix shows, murder cases are solved and neatly wrapped up in the end. This leaves the reader or audience with the satisfaction of knowing who done it and probably why.

That’s not always the truth in real life. Many murders go unsolved for a long time. Some go cold and are never resolved. Statistics vary according to region, but probably a quarter of murders never get cleared.

Thankfully, most murders are easy to solve. They’re “smoking guns” where the killer and victim knew each other, the killer left a plethora of evidence at the scene or took it with him, witnesses saw the murder take place, or the bad guy confessed to the crime. That’s really all there is to getting caught for committing a murder.

So, why do roughly twenty-five percent of people get away with murder? It’s because they don’t make one of these four fatal mistakes. Let’s look at each in detail and how you can get away with murder.

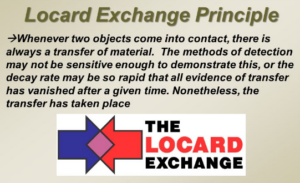

Did you ever hear of Locard’s Exchange Principle? It’s Murder Investigation 101. Dr. Edmond Locard was a pioneer in forensic science. Dr. Locard held that at every crime scene the bad guy would leave evidence behind that would connect them to the offense. Locard summed it up this way:

“Wherever he steps, whatever he touches, whatever he leaves, even unconsciously, will serve as a silent witness against him. Not only his fingerprints or his footprints, but his hair, the fibers from his clothes, the glass he breaks, the tool mark he leaves, the paint he scratches, the blood or semen he deposits or collects. All of these, and more, bear mute witness against him. This is evidence that does not forget. It is not confused by the excitement of the moment. It is not absent because human witnesses are. It is factual evidence. Physical evidence cannot be wrong, it cannot perjure itself, it cannot be wholly absent. Only human failure to find it, study and understand it, can diminish its value.”

Dr. Locard was absolutely right—most of the time. That quote was from the early 1900s. It was long before the sophistication of DNA profiling and amplifying light to find invisible fingerprints. Today, trace evidence shows up at the micro level, and there’re ingenious inventions used to find it. But… not always.

I’m familiar with a high-profile and unsolved murder case from 2008 where two killers enticed a female realtor to a house and savagely stabbed her to death. It’s a long story. A complicated story. And, so far, they’ve got away with the murder.

The victim was totally innocent. She was set-up as a sacrifice to protect someone else who was a police informant. The police know full well who the killers are—a Mexican man and woman from the Sinaloa drug cartel—but they’ve never been charged. It’s because they left no evidence of their identity at the scene. They’ve also never broken the other three murderer-catching rules.

There’s more to scene evidence than DNA and fingerprints. There are dozens of evidentiary possibilities including hairs, fibers, footwear impressions, chemical signatures, organic compounds, match heads, cigarette butts, expended shell casings, spit chewing gum, a bloody glove or a wallet with the killer’s ID in it. (Yes, that happened.)

The flip side of Locard’s Exchange Principle is the perpetrator removing evidence from the scene that ties them back to it. This can be just as fatal to the get-away-with-it plan as left-behind evidence. And, it happens all the time.

Going back to the unsolved realtor murder, there’s no doubt the killers left with the victim’s blood on their hands, feet and clothing. This innocent lady was repeatedly shived. The coroner report states her cause of death was exsanguination which is the medical term for bleeding out.

Going back to the unsolved realtor murder, there’s no doubt the killers left with the victim’s blood on their hands, feet and clothing. This innocent lady was repeatedly shived. The coroner report states her cause of death was exsanguination which is the medical term for bleeding out.

For sure, her killers had blood on them. But, they made a clean escape and would have disposed of their blood-stained clothes. That goes for the knife, as well. Further, the killers did not rob the victim. They didn’t steal her purse, her identification, her bank cards or even the keys to her new BMW parked outside.

The killers also didn’t exchange digital evidence to be traced. They used a disposable or “burner” phone to contact the victim to set up the house showing. It was only activated under a fake name for this one purpose and was never used again. The phone likely went the same place as the bloody clothes and knife.

I once heard a judge say, “There’s nothing more unreliable than an eyewitness.” I’d say that judge was right, at least for human eyewitnesses.

Today’s technology makes it hard not to be seen entering or exiting a murder scene. There’s video surveillance galore. Pretty much everywhere you go in an urban setting, electronic eyes are on you. You’re on CCTV at the gas station, the supermarket, the bank, in libraries, government buildings, transit buses, subways and on the plane.

In bygone lore, the killer often wore a disguise. That might have fooled human surveillance, but it’s hard to trick cameras that record evidence like get-away vehicles with readable plates. It’s also hard to disguise a disguise that can be enlarged on film to reveal uniquely identifiable minute characteristics.

Back to the unsolved realtor slaying again. The killers were seen by two independent witnesses when they met their victim in the driveway outside the show home. One witness gave the police a detailed description of the female suspect and worked with an artist to develop a sketch. It’s an eerie likeness to the Mexican woman who is a prime person-of-interest along with her brother—a high-ranking member of the El Chapo organization.

Unfortunately, there’s just not enough evidence to charge the Mexicans. They left no identifiable trace evidence behind at the crime scene. Whatever evidence they might have taken from the scene hasn’t been found. There was no video captured and the eye-witnesses can’t be one hundred percent positive of visual identity.

There’s also the fourth missing piece to the puzzle.

Murderers are often convicted because they confessed to the crime. Sometimes, they confess to the police during a structured interrogation. Sometimes, they confess to a police undercover operator or paid agent during a sting operation. Sometimes, their loose lips sink their ship by telling an acquaintance about doing the murder. And sometimes, they’re caught bragging about the murder on electronic surveillance like in a wiretap or through a planted audio listening device—a bug.

Police also arrest and convict murderers after an accomplice turns on them and decides to cooperate with the investigation in exchange for a lesser sentence. Then, there are the revenge situations. The murderer has confessed to an intimate partner who they thought they could trust and couldn’t.

That has yet to happen in the unsolved female realtor murder. There is no doubt—no doubt—that a group of people know what happened in her murder. It’s known, with probable certainty, who the Mexican pair are. It’s also known, with probable certainty, who the real police informant was and who conspired to protect them by offering the innocent victim as a sacrificial slaughter to appease the Sinaloa cartel’s “No-Rat” policy.

This murder case can be solved once someone in the group decides to reveal evidence implicating the killers. That likely won’t be anything in the Locard arena or in the eye-witness region. It’ll be an exposed confession that will solve this case.

Someone will eventually talk. The current problem is that everyone in the conspiracy circle is connected by being blood relatives, being a member of the Hispanic community and being involved in organized crime. Their motive to talk is far outweighed by their motive to stay silent.

If you’re a mystery/thriller/crime writer, always consider these four crime detection principles when working your plot. No matter how simple or complex your plot may be, the solution will come down to one or more of these points. If it doesn’t, then your antagonist is going to get away with murder.

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective and forensic coroner, now an investigative crime writer and successful indie author. Garry also hosts a popular blog at his website DyingWords.net and is a regular contributor to the HuffPost.

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective and forensic coroner, now an investigative crime writer and successful indie author. Garry also hosts a popular blog at his website DyingWords.net and is a regular contributor to the HuffPost.

Garry Rodgers lives on Vancouver Island in British Columbia at Canada’s west coast. He’s a certified 60-Tonne Marine Captain and spends a lot of time around the saltwater. Follow Garry on Facebook, Twitter and BookBub. He has stuff on Amazon, Kobo and Nook, too.

Self-doubt is a crippling condition for any artist. (Spoiler: It never goes away. You just learn to manage it.) For young or inexperienced artists–hereinafter called writers because this is a blog about writing–self-doubt can be paralyzing. You write something you think is pretty good, but when you show it to your “beta readers” they have suggestions, so forward progress stops on your story.

The writer’s internal monologue goes something like this: I thought that description of the lightning strike was pretty strong. But if Beta George didn’t like it, there must be something wrong. He said he didn’t like the word “struck” because he thought it was a cliche. And he said Main Character Harriett wasn’t scared enough. I don’t get why she’d be more scared than she is, but if Beta George thinks. . .

I call this navel gazing. No further work gets done on the story because the writer is wrapped around his own axle trying to make Beta George happy–even if it’s against the writer’s own better judgment.

Does this scenario sound familiar to anyone: Mary has been working on her story for eighteen months but hasn’t gotten past Chapter Three. Every time she tries to move forward, she looks back and realizes that what she’s written is terrible. She wonders why she ever thought she could write a book, maybe has a little cry or maybe a big cocktail, and then she goes back to the beginning.

NOTE: Up to and excluding the part where she starts over, this is a process I go through with every book. Twenty-one of them. It’s part of the process. Literally, writing crappy prose is a necessary element of the journey to get to the end of a project. And not just at the beginning of a career. Every. Friggin’. Book.

Having done this a few times grants the advantage of having confidence in the crappy parts. I know that once the creative boiler comes up to pressure and I’m steaming through the story, I’ll be able to take care of damage control. But I have to get up to pressure. I have to move the story forward.

I’m going to share my strategy for managing doubt and crappy prose, and then I’m going to share how I think you should handle it until you feel confident that your boiler is sound.

I start every writing session by rewriting what I wrote in the previous two sessions. Then, when I finish today’s session of moving forward, I intentionally do not go back and edit. That’s tomorrow’s job, after things are less fresh in my head. Rewriting takes about an hour most days, and then I forge ahead. By the time I get to the end of the first draft, I’m really on my third or fourth draft, and all I need is a quick pass for a polish.

My system works for me because a) I’ve been doing this for a very long time, and b) I force myself to add at least a thousand words to yesterday’s count. Two thousand is better, and I think my record is 8,900. I don’t want to do that again.

Here’s my suggestion for others: Eyes Front. Don’t look back. Period. Hard stop.

Pick a targeted word count or a date on the calendar (think 10,000 words or three weeks–a real stretch). Until that milestone is reached, you are forbidden to look back at what you’ve written. Keep the story moving forward. Only forward. Get that boiler churning. Fall in love with your story again. And no cheating! If you forget what you named that guy in Chapter Two, mark the spot with asterisks and keep going.

When you reach your milestone, you MUST congratulate yourself for having met it. If you’re sailing your book at full speed through calm waters, set another goal and keep pressing on. If you need to go back to fix stuff (all those asterisks, for example), go for it. Make all the changes you feel are necessary, but remember that you still owe yourself a thousand words of forward progress.

Don’t let your book run aground while you’re cleaning the bilges.

What do you think, TKZers? Worth a try?

(Disclaimer: The quiz part of this post I lifted from one my own old posts. Don’t sue me.)

By PJ Parrish

Now pay attention, kittens and bo’s, there’s a quiz at the end of this one.

I had my usual hot date this past Sunday. He’s a dream-boat of a guy and he never disappoints me. We met in a bar in Toronto back in my salad days, and had a Same Time Next Year sort of thing going on. But then we drifted off into other things and lost touch. But a couple years ago, I ran into him again and it was like…magic.

Okay, before I get in trouble here, I will tell you that my hot date is Eddie Muller. I first met Eddie oh, maybe seventeen years ago at a Bouchercon conference. Back then, he was still writing crime fiction and had won the Shamus Award for his debut novel The Distance. My sister Kelly and I were nominated for our third book Paint It Black. We lost, but I remember Eddie was very sweet to us. Bought me a drink, as I recall.

Fast forward to 2017 and I ran into Eddie again while I was channel surfing. He had a great new gig as the host of Turner Classic Movie’s Noir Alley series. He would introduce each film, drawing on his lifelong love of the genre. We now hook up every Sunday morning on TCM. (This Sunday it’s Underworld U.S.A., starring Cliff Robertson who’s out to avenge the murder of his father even as he falls in love with a femme fatale named Cuddles, whom he just might have to kill.)

It was Eddie who introduced me to what would become my favorite noir film A Kiss Before Dying. It was Eddie who showed me that my teenage crush Dr. Ben Casey was really a creep in Murder By Contract. It was Eddie who led me to the novels of James M. Cain via Double Indemnity. Here’s Eddie talking about that seminal classic:

I am still trying to catch up on my noir reading. (I didn’t get to The Maltese Falcon until about ten years ago, I confess). Digesting noir, with its emphasis on oppressive mood and shadowed morality, with its lean mean style, has helped me find my own voice as a writer. I am not a true neo-noir practitioner, but I feel a deep connection to its dark heart. One of the best compliments I ever got was when Ed Gorman wrote of our book Thicker Than Water: “The quiet sadness that underpins it all really got to me, the way Ross Macdonald always does.”

A couple Christmases ago, my husband gave me The Black Lizard Big Book of Pulps. It’s a compilation of the best crime stories from the “golden age” of pulp crime fiction — the ’20s through the ’40s. It’s about the size of an old Manhattan phone book. And to be really honest, parts of it read about as well.

Many of these guys were dismissed as the hacks of their day, churning out their stories for cheaply printed magazines like “Black Mask” and “Dime Detective.” Yeah, they were lurid, the syntax cringe-worthy, the plots thin or nonsensical. But they tapped into a popular need for a new kind of human hero. The most memorable of the heroes became the prototypes for much of what we are seeing in our crime fiction today — lone wolves fighting for justice against all odds but always on their own different-beat terms. Would we have Harry Bosch without the Continental Op? Jack Reacher without Simon Templar? No way…

And while we’re at it, let’s not get sucked into the notion that noir was only a guy thing. Valerie Taylor had a career churning out books like The Girls In 3B, a classic ’50s pulp tale showcasing predatory beatnik men, drug hallucinations, and secret lesbian trysts. (Her books, among others, have been reissued by Feminist Press.) And would we have Megan Abbott or Sarah Gran without Dorothy B. Hughes, who wrote the twisty indictment of misogyny In A Lonely Place (the source of the Bogart movie)? Doubtful…

To be sure, not all the old stories — like many of the movies — have aged well. The slang sounds vaguely silly now, the sexism and racism we can explain away as anachronistic attitudes. But the armature these writers created is still sturdy.

Especially in pure writing style. I think we can read these stories now mainly to appreciate the streamlined locomotive style that propels these stories along their tracks. When you read them, you can almost hear James M. Cain whispering: “I’m not going to dazzle you with my writing. I’m going to tell you a helluva story.”

These guys sure knew what to leave out. Here’s a passage from Paul Cain’s “One Two Three:”

I said: “Sure — we’ll both go.

Gard didn’t go for that very big, but I told him that my having been such a pal of Healy’s made it all right.

We went.

Not: And then we left the apartment and got in my roadster and set out. We took Mulholland Drive out of the canyon and arrived just before dusk. Just: We went.

How can you read that and not smile? I heartily recommend the Big Book of Pulps. And if you haven’t connected with Eddie on Noir Alley, you’re missing out on some of the best stuff television has to offer.

And now, in honor of our pulp forefathers, I am offering up this little quiz of pulp diction slang for your amusement. Answers at the end. And don’t chance the chisel for a cheap bulge, bo. We Jake?

DEFINITIONS.

1. Ameche

2. Kicking the gong around

3. Wooden kimono

4. cheaters

5. Gasper

6. Hammer and saws

7. Orphan papers

8. Wikiup

9. Bangtails

10. Can-opener

TRANSLATIONS

11. I had been ranking the Loogan for an hour and could see he was a right gee. It was all silk so far.

12. I stared down at the stiff. The bim hadn’t been chilled off. Definitely a pro skirt who had pulled the Dutch act.

13. I got a croaker ribbed up to get the wire.

14. By the time we got to the drum the droppers had lammed off. Another trip for biscuits…

Answers:

1. telephone

2. taking opium

3. coffin

4. sunglasses

5. cigarette

6. Police

7. Bad checks

8. Home

9. Horses

10. Safecracker

11. I had been watching the man with the gun for an hour and could tell he was an okay guy. Everything was cool so far.

12. I stared at the body. The woman hadn’t been murdered. She was definitely a prostitute who had committed suicide.

13. I have arranged for a doctor to get the information.

14. By the time we got to the speakeasy, the hired killers had left. Just another trip for nothing…