Discover: verb. to see, get knowledge of, learn of, find, or find out; gain sight or knowledge of (something previously unseen or unknown).

Before I begin, let me note that I’m not addressing the issues of the treatment of indigenous peoples by the early explorers. I’m simply looking at the accidental discovery of the Americas.

One might argue that Columbus didn’t “discover” the New World since people already lived there. Others may point out that Norsemen landed in Newfoundland hundreds of years before Columbus. But the discovery in 1492 was the singular event that led to a worldwide understanding of the geography of our planet and resulted in an exciting new age of exploration.

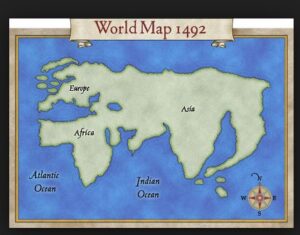

In the fifteenth century, many European leaders longed for quick access to the riches of the Far East, but land travel to Asia was perilous. The only known sea route was by sailing south along the west coast of Africa, around the Cape of Good Hope, across the Indian Ocean and on to Asia. But that was a long, slow journey.

Into this moment in history stepped the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus, and as we all know, he proposed a different solution to the problem: sailing directly west from Europe to Asia. Columbus wasn’t the only person who believed the Earth was round – most educated people of that era agreed – but he was the one who was willing to risk his life on it.

Columbus was an excellent seaman and one of the most experienced navigators of his time. However, the data he used to calculate the length of the voyage was faulty. The circumference of the Earth was considered to be much smaller than it actually is, and the Asian land mass was thought to extend much farther to the east than it does. Using these data, he calculated the distance from the Canary Islands to Japan to be about 2,400 miles. Actually, it’s more than 10,000 miles. One can only wonder if he would have attempted the voyage if he had known the true distance.

By 1484, Columbus had drawn up plans for a westward expedition into the Atlantic Ocean to fulfill the dream of finding a faster route to Asia and its riches, but his request for support was turned down by every government he approached as being too risky. Undeterred, he kept trying, and eventually he secured funding from several sources including the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella. The rest, as they say, is history.

***

Perhaps we can define Christopher Columbus as the first hybrid plotter/pantser. (Okay, now you see where I’m going with this.) There are a lot of similarities. Columbus had an end goal in mind, but he didn’t simply hop in a boat and head out. His persistence and hard work got his voyage funded. He used the knowledge that was available to him at the time to plan his voyage (albeit his calculation of the length of the trip was woefully mistaken). He was a skilled navigator who had made many successful voyages around the coasts of Europe, and he wisely decided on the starting point from the Canary Islands to take advantage of the favorable trade winds. Still, to set sail into the unknown was an act of courage and faith that I suspect few had then or have today.

Of course, he could not have foreseen the magnificent surprise that awaited him some weeks after he set sail.

***

The Discovery Method in writing is often defined as pantsing or “writing by the seat of your pants.” But maybe it’s closer to the Christopher Columbus hybrid method. Is using this approach a way to happen onto an idea or a phrase that we wouldn’t have come upon otherwise? Will the discovery method offer us the opportunity to learn more about ourselves by launching into the unknown with a partially-developed plan? Is it possible to produce a work that is new and revolutionary through the discovery method?

So, TKZers: Are you a plotter? A pantser? Or a hybrid plantser? Have you happened onto any unexpected discoveries in your writing? Maybe you’ve experimented with a new idea to extend yourself beyond the safe haven of what has always worked for you.

Is the possibility of discovering something new worth the risk of failure by launching out into the unknown?

I love rooting around in

I love rooting around in

By Elaine Viets

By Elaine Viets

Want to go trendy? For a while every third book had “Girl” in the title. That trend started with novels like Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl and Paula Hawkins’ The Girl on the Train, not to mention The Girls With the Dragon Tattoo by Stieg Larsson. None of these women were the girl next door, but their books sold. By the way, The Girl Next Door was used by a wide range of writers, from Brad Parks to Ruth Rendall. It’s even a horror story.

Want to go trendy? For a while every third book had “Girl” in the title. That trend started with novels like Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl and Paula Hawkins’ The Girl on the Train, not to mention The Girls With the Dragon Tattoo by Stieg Larsson. None of these women were the girl next door, but their books sold. By the way, The Girl Next Door was used by a wide range of writers, from Brad Parks to Ruth Rendall. It’s even a horror story.

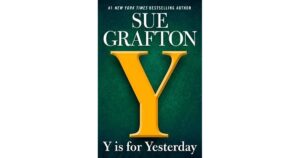

Series titles: Sue Grafton has her alphabet series, beginning with A Is for Alibi and ending with Y Is for Yesterday. Mary Higgins Clark and her partner-in-crime Alafair Burke have a song title series, starting with You Don’t Own Me. Stephanie Plum uses numbers. Her latest is Game on: Tempting Twenty-eight.

Series titles: Sue Grafton has her alphabet series, beginning with A Is for Alibi and ending with Y Is for Yesterday. Mary Higgins Clark and her partner-in-crime Alafair Burke have a song title series, starting with You Don’t Own Me. Stephanie Plum uses numbers. Her latest is Game on: Tempting Twenty-eight. Enter to win a free copy of Life Without Parole, my latest Angela Richman, death investigator mystery. Stop by Kings River Life magazine:

Enter to win a free copy of Life Without Parole, my latest Angela Richman, death investigator mystery. Stop by Kings River Life magazine:

Those dang pesky buggers that sneak into first drafts and weaken the writing are called filler words and phrases—also known as fluff.

Those dang pesky buggers that sneak into first drafts and weaken the writing are called filler words and phrases—also known as fluff.

So here we are on a toboggan hurtling down the snowy mountain called 2022. Seems like a good time to take a look at the current state of book publishing, the better to avoid the rocks, tree stumps, and cliffs scattered all over the slope.

So here we are on a toboggan hurtling down the snowy mountain called 2022. Seems like a good time to take a look at the current state of book publishing, the better to avoid the rocks, tree stumps, and cliffs scattered all over the slope.