Let me apologize to the Brave Writer who submitted this first page. A mix-up in communication caused me to think Brian sent this to another TKZer. Sorry! And thank you for your patience. My comments will follow.

***

Title: The Puzzle Within

Genre: Romantic Suspense

Arizona Powers slammed her palm into the office wall, ignoring the stinging sensation. Unbelievable. “Are you kidding me? I’m not doing that. I’m a federal agent, not a babysitter.” Her boss had clearly lost his mind. She spun on her hiking shoe, locking eyes with Senior Special Agent Matt Updike. Her fingers fidgeted with a button on her shirt. I deserve a second chance.

Matt shoved his chair backward, rising with his hands splayed over the glass surface. “I’m not kidding. You are doing this,” he said, angling his bushy eyebrows and closing the distance between them in two steps. “You don’t have a choice.” His hot, stale coffee breath blasted her skin, and a vein in his neck bulged.

Reclining her head to make eye contact with a man nearly a foot taller than herself, Ari wrinkled her nose, crossed her arms, but refused to back down. “You can’t force me to do this. I’ll take it to the top.” All the way to the Director if necessary.

Matt’s energy deflated, a muscle twitching in his cheek. “This assignment came from the top. From the Director himself. The shrink doesn’t believe you’re ready,” he said, placing a warm hand on her shoulder. His expression softened. “Not yet.”

Ari shrugged, knocking his hand away, and stalked to the other side of the room. She rested her hands on a bookshelf, her eyes falling upon the photo of Matt’s smiling family taken at Disneyland last summer. The FBI was her family, and she didn’t need sympathy. She needed her job back. With a sigh, she rotated to face her boss. “But why me? Why isn’t DSS handling this?”

Shouldn’t the Diplomatic Secret Service be handling this problem? They’re responsible for Ambassador Van Sloan and his spoiled daughter, Bianca—the biggest brat in diplomatic circles. Growing up in the consulate with the world at her fingertips and a silver spoon in her mouth, the college student didn’t comprehend the word “no.”

I don’t have time for this. I’ve got cases to solve and missing children to find. A knot formed in her stomach.

Matt cleared his throat and returned to his seat.

Ari’s pulse flickered in her neck. “What aren’t you telling me?” Apprehension tinged her voice.

He swallowed. “DSS is handling it.” His eyes darted to a manila envelope on his desk. “You’re being ‘borrowed’ for the time being.”

***

Let’s first discuss all the things Brave Writer did right.

- Good grasp of POV

- Story starts with a goal: To get out of babysitting a diplomat’s daughter.

- Includes a complication: The boss is forcing her to go.

- Raises story questions: Why is Arizona not ready for FBI work? Why did the psychiatrist evaluate her?

- Includes a subtle clue that tells us Arizona isn’t dressed for work—her hiking boot—which implies she’s on leave after an incident or came in on her day off.

If we put all these puzzle pieces together, the assumption is something bad happened to Arizona.

Kudos to you, Brave Writer. You’ve worked hard to hone your craft.

Now for some tough love.

The bones of intrigue are there, but it’s overshadowed by too many body cues and random details that add nothing of value. Here are the first two paragraphs with my comments in blue.

Arizona Powers slammed her palm into the office wall, ignoring the stinging sensation. This first line has no context. It’s a reaction without a motivation, or an effect without a cause. If, say, a grizzly bear was advancing on our MC, we wouldn’t first show the MC’s reaction. We’d show the grizzly bear huff or stomp the ground. Then the MC could react. Unbelievable. “Are you kidding me? I’m not doing that. I’m a federal agent, not a babysitter.” Her boss had clearly lost his mind. She spun on her hiking shoe This body cue implies she’s changing directions to leave, yet the rest of the sentence implies she’s entering her boss’s office. When put together, these two body cues cancel each other out and cause confusion., locking eyes with Senior Special Agent Matt Updike. I realize some writers use “locking eyes” but I immediately envision floating eyeballs. “Locking gazes” avoids confusion. But again, without knowing if she’s leaving or entering the office, the scene remains scrambled in this reader’s mind. Her fingers fidgeted with a button on her shirt. And now, she’s fidgeting, which implies nervousness. However, slamming a hand into a wall, locking gazes, and the inner monologue and dialogue all implies anger and/or defiance. Choose one emotion and stick with it. We haven’t even gotten to the second paragraph, and already the MC has experienced a plethora of conflicting emotions. I deserve a second chance.

Matt shoved his chair backward, rising with his hands splayed over the glass surface. Glass surface of what? “I’m not kidding. <- this adds nothing of value, nor does this -> You are doing this,” he said, angling his bushy eyebrows <- I have no idea what this means. Is he consciously angling his bushy eyebrows at something? Doubtful. And if he is, we’ve slipped out of Arizona’s POV. and closing the distance between them in two steps. “You don’t have a choice.” His hot, stale coffee breath blasted her skin Face? Nose? Be specific. ’Course, shoving his chair backward is all you need to portray anger. All these other emotional cues distract from the dialogue. It’s too much. A good exercise for you may be to limit one emotion per character per page. It’ll force you to focus on strengthening the dialogue, inner monologue, and the narrative., and a vein in his neck bulged.

Let’s move on…

What if you started by showing Ari trying to control the diplomat’s reckless daughter (and failing)? Then this whole opener could be threaded through the narrative in a more organic way.

Example:

I didn’t become a federal agent to babysit a diplomat’s brat.

That one line of inner dialogue shows what you’ve conveyed in this first page. Please don’t get discouraged. We’ve all started novels too soon. And many of us continue to learn that lesson over and over and over. I wrote three different openers to my current WIP before I landed on one that worked, and it’ll be my 22nd book.

One last comment…

Because the out-of-control diplomat kid is a familiar trope, you need to work twice as hard to twist it in a way that’s fresh and new. It likens to the alcoholic cop or homicide detective who’s haunted by the cases he couldn’t solve. I can see that you have worked hard on your craft—otherwise I’d be handling you with kid gloves—so I’ll assume you have a fresh take. Which is great. I only bring it up to make you aware. Okay? Now, go write your bestseller. You’ve got the writing chops to do it. 😉

Over to you, TKZers. Please add your thoughtful suggestions for this Brave Writer.

USA Today bestselling author Karen Odden received her PhD in English from NYU, writing her dissertation on Victorian literature, and taught at UW-Milwaukee before writing mysteries set in 1870s London. Her fifth, Under a Veiled Moon (2022), features Michael Corravan, a former thief turned Scotland Yard Inspector; it was nominated for the Agatha, Lefty, and Anthony Awards for Best Historical Mystery. Karen serves on the national board of Sisters in Crime, and she lives in Arizona where she hikes the desert while plotting murder. Find out more about Karen’s books and writing workshops at

USA Today bestselling author Karen Odden received her PhD in English from NYU, writing her dissertation on Victorian literature, and taught at UW-Milwaukee before writing mysteries set in 1870s London. Her fifth, Under a Veiled Moon (2022), features Michael Corravan, a former thief turned Scotland Yard Inspector; it was nominated for the Agatha, Lefty, and Anthony Awards for Best Historical Mystery. Karen serves on the national board of Sisters in Crime, and she lives in Arizona where she hikes the desert while plotting murder. Find out more about Karen’s books and writing workshops at

Anne R. Allen is a popular blogger and the author of the bestselling Camilla Randall Mysteries as well as the Boomer Women Trilogy and the anthology Why Grandma Bought that Car (Kotu Beach Press.) Her most recent mystery is Catfishing in America (Thalia Press) a comic look at romance scams. Her mystery The Gatsby Game is being published in French at the end of this month. Anne’s nonfiction guide, The Author Blog: Easy Blogging for Busy Authors, is an Amazon #1 bestseller that was named one of the 101 Best Blogging Books of All Time by Book Authority. She’s also the co-author, with Catherine Ryan Hyde, of the writer’s guide How to Be a Writer in the E-Age. She blogs with NYT million-copy seller, Ruth Harris, at “Anne R. Allen’s Blog…with Ruth Harris.” You can find them at

Anne R. Allen is a popular blogger and the author of the bestselling Camilla Randall Mysteries as well as the Boomer Women Trilogy and the anthology Why Grandma Bought that Car (Kotu Beach Press.) Her most recent mystery is Catfishing in America (Thalia Press) a comic look at romance scams. Her mystery The Gatsby Game is being published in French at the end of this month. Anne’s nonfiction guide, The Author Blog: Easy Blogging for Busy Authors, is an Amazon #1 bestseller that was named one of the 101 Best Blogging Books of All Time by Book Authority. She’s also the co-author, with Catherine Ryan Hyde, of the writer’s guide How to Be a Writer in the E-Age. She blogs with NYT million-copy seller, Ruth Harris, at “Anne R. Allen’s Blog…with Ruth Harris.” You can find them at

The rhetorical triangle is a concept that rhetoricians developed from the Greek philosopher Aristotle’s idea that effective persuasive arguments contain three essential elements: logos, ethos, and pathos.

The rhetorical triangle is a concept that rhetoricians developed from the Greek philosopher Aristotle’s idea that effective persuasive arguments contain three essential elements: logos, ethos, and pathos.

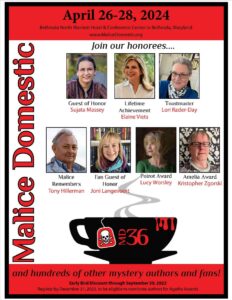

The Malice Domestic mystery conference is honoring me with the Lifetime Achievement Award for Malice 36 April 26-28, 2024. Malice Domestic is an annual fan convention in Bethesda, Maryland. I’m thrilled to be part of a star-studded line-up next year.

The Malice Domestic mystery conference is honoring me with the Lifetime Achievement Award for Malice 36 April 26-28, 2024. Malice Domestic is an annual fan convention in Bethesda, Maryland. I’m thrilled to be part of a star-studded line-up next year. The Dead of Night, my new Angela Richman, death investigator mystery, is available in book stores and online:

The Dead of Night, my new Angela Richman, death investigator mystery, is available in book stores and online:

By Elaine Viets

By Elaine Viets