– A glimpse into the minds of acquiring editors and judges for short (or any) fiction

– A glimpse into the minds of acquiring editors and judges for short (or any) fiction

Jodie Renner, editor & author @JodieRennerEd

Have you tried your hand at writing short stories yet? If not, what’s holding you back? As award-winning blogger Anne R. Allen said in an excellent article in Writer’s Digest magazine, “Bite-sized fiction has moved mainstream, and today’s readers are more eager than ever to ‘read short.’” To check out Anne’s “nine factors working in favor of a short story renaissance,” see “9 Ways Writing Short Stories Can Pay off For Writers“, and there’s more in her post, Why You Should be Writing Short Fiction.

Here’s another Argument for Writing Short Stories, by Emily Harstone. She says, “Writers who are serious about improving and developing their craft should write short stories and get editorial feedback on them, even if they are never planning on publishing these short stories. Short stories are one of the best ways to hone your craft as a writer.”

Okay, you’ve decided to take the plunge and craft a few short stories. Good for you! Next step: Consider submitting some of them to anthologies, magazines, or contests. But wait! Before you click “send,” be sure to check out my 31 Tips for Writing a Prize-Worthy Short Story, then go through your story with these tips in mind and give it a good edit and polish – possibly even a major rewrite – before submitting it.

What are some of the common criteria used by publications and contests when evaluating short story submissions?

I recently served as judge for genre short stories for Writer’s Digest Popular Fiction Contest, where I had to whittle down 139 entries to 10 finalists, but I wasn’t provided with a checklist or any specific criteria. However, a friend who regularly submits short stories to anthologies, magazines, and contests recently received a polite rejection letter from the editor of a literary magazine, along with a checklist of possible reasons, with two of them checked off specifically relating to her story.

While useful, the list of possible weaknesses is very “bare bones” and cries out for more detail and specific pointers. Editors, publishers, and judges are swamped with submissions and understandably don’t have time to give detailed advice for improvement to all the authors whose stories they turn down. Perhaps you could help me interpret and flesh out some of these fairly cryptic, generic comments/criticisms, and add any additional points that occur to you, or checklists you may have received.

Can you think of other indicators of story weaknesses that could be deal-breakers for aspiring authors submitting short stories for publication? Or do you have links to online publishers’ checklists for fiction submissions? Please share them in the comments below.

Here’s the list my friend received, with my comments below each point. Do you have comments/interpretations to add?

Checklist from a Publisher/Editor/Publication in Response to Short Story Submissions

“Thank you for submitting your short story to …. We’ve given your work careful consideration and are unable to offer you publication. We do not offer in-depth reviews of rejected submissions, due to time constraints. Briefly, we feel your submission suffered from one/several of the following common problems:”

– “Tone or content inappropriate for…” (publisher / publication / anthology / magazine)

Check their submission guidelines and read other stories they’ve accepted to get an idea of the genre, style, tone, and content they seem to prefer.

– “Stylistic and grammatical errors; too many typos”

Be sure to use spell-check and get someone with strong skills in spelling, grammar, punctuation, and sentence structure to check it over carefully for you. Read it out loud, and where you pause briefly, put in a comma. Where you pause a little longer, put in a period. You could also try using editing software or submit it to a professional freelance editor. This last choice has the most likelihood of helping you hone your fiction-writing skills.

– “Structure problems”

For a novel, this could mean some chapters could be rearranged, shortened, or taken out. What do you think it could mean for a short story? Too many characters? Too many plot lines?

– “Formatting problems made reading frustrating”

Be sure your story is in a common font, like Times New Roman, 12-point, and double-spaced, with only one space after periods and one-inch margins on all four sides. Don’t boldface anything or use all caps. For more white space and ease of reading, divide long blocks of text into paragraphs. Start a new paragraph for each new speaker. Indent paragraphs. Don’t use an extra line space between paragraphs. Use italics sparingly for emphasis. For more specifics on formatting, see “Basic Formatting of Your Manuscript (Formatting 101)”.

– “Characters were problematic/unbelievable/unlikeable”

Your characters’ decisions, actions and motivations need to fit their personality, background, and character. And make sure your protagonist is likeable, someone readers will want to root for.

– “Content and/or style too well-worn or obvious”

This likely refers to a plot that’s been done a million times, with cookie-cutter characters and a predictable ending.

– “Word choice needs refinement”

This one could cover the gamut from overused, tired words like nice, good, bad, old, big, small, tall, short to overly formal, technical, or esoteric words where a concrete, vivid, immediately understandable one would be more effective.

– “Overbearing or heavy-handed”

This probably refers to a story where the author’s agenda is too obvious, too hard-hitting, maybe even a bit “preachy,” rather than subtle, allowing the reader to draw their own conclusions.

– “Nothing seems to have happened”

To me, this probably indicates no major problem or dilemma for the protagonist, not enough meaningful action and change, and insufficient conflict and tension.

– “Strong beginning, then peters out”

This is an indicator that your plot needs amping up and you need to add rising tension, suspense, and intrigue to keep readers avidly turning the pages. Also, flesh out your characters to make them more complex. Give your protagonist secrets, regrets, inner conflict, and a strong desire that is being thwarted.

– “Needs overall development and polish.”

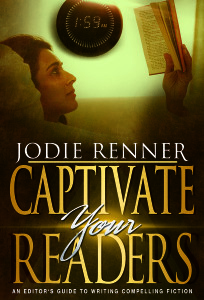

This indicates you likely need to roll up your sleeves and hone your writing skills. Read some writing guides (like those by James Scott Bell or my Captivate Your Readers, Fire up Your Fiction, or Writing a Killer Thriller). Also, read lots of highly rated published short stories, paying close attention to the writers’ techniques. Here’s where a critique group of experienced fiction writers or some savvy beta readers or a professional edit could help.

– “We didn’t get it.”

This is likely a catch-all category that means the story didn’t work for a number of reasons. This could be an indicator to put this story aside and hone your craft, critically read other highly rated stories in your genre, then, using your new skills, craft a fresh story.

“While all of these criticisms open doors to further questions, we regret that we cannot be more constructive….”

That’s understandable. They just don’t have time to critique or mentor every writer who contacts them. But I hope my comments above help aspiring fiction writers hone your craft and get your stories published – or even win awards for them. Good luck! For tips on how to actually submit, check out “Writing Short Stories? Don’t Make These 4 Submission Mistakes“.

Jodie Renner is a freelance fiction editor and the award-winning author of three craft-of-writing guides in her series An Editor’s Guide to Writing Compelling Fiction: Captivate Your Readers, Fire up Your Fiction, and Writing a Killer Thriller. She has also published two clickable time-saving e-resources to date: Quick Clicks: Spelling List and Quick Clicks: Word Usage. You can find Jodie at www.JodieRenner.com, www.JodieRennerEditing.com, her blog, http://jodierennerediting.blogspot.com/, and on Facebook, Twitter, and Google+.

Jodie Renner is a freelance fiction editor and the award-winning author of three craft-of-writing guides in her series An Editor’s Guide to Writing Compelling Fiction: Captivate Your Readers, Fire up Your Fiction, and Writing a Killer Thriller. She has also published two clickable time-saving e-resources to date: Quick Clicks: Spelling List and Quick Clicks: Word Usage. You can find Jodie at www.JodieRenner.com, www.JodieRennerEditing.com, her blog, http://jodierennerediting.blogspot.com/, and on Facebook, Twitter, and Google+.

So I just took an online personality test offered by the The University of Cambridge, and now I’m trying to absorb a few puzzling facts about my personality. Based on the principles of psychometrics, the test measures a person’s personality profile on the classical “big five” personality traits (Extroversion, Emotionality, Openness, Agreeableness and Conscientiousness). The test also classifies one’s general personality “type”.

So I just took an online personality test offered by the The University of Cambridge, and now I’m trying to absorb a few puzzling facts about my personality. Based on the principles of psychometrics, the test measures a person’s personality profile on the classical “big five” personality traits (Extroversion, Emotionality, Openness, Agreeableness and Conscientiousness). The test also classifies one’s general personality “type”.

abducted them and their situation is grim. Their futures can be measured in minutes, not years. That would be enough of a conflict for most writers. Not for me though. I have to take that awful scenario and make it worse. Zoë has to make a horrible decision—make a futile attempt to save Holli or use Holli as the distraction to help her escape. Zoë makes the hard decision—she escapes with her life and has to live with the guilt and shame of that single act of self-preservation.

abducted them and their situation is grim. Their futures can be measured in minutes, not years. That would be enough of a conflict for most writers. Not for me though. I have to take that awful scenario and make it worse. Zoë has to make a horrible decision—make a futile attempt to save Holli or use Holli as the distraction to help her escape. Zoë makes the hard decision—she escapes with her life and has to live with the guilt and shame of that single act of self-preservation. eries and rigs that prevented noxious chemicals and gases that come up with the crude oil from getting into the atmosphere. That kind of work meant dealing with contingencies. If a valve failed, what was the bypass? If the bypass failed, what was the bypass’ bypass? It was all part of designing to multiple levels of failure. It’s no different than my flying experiences. Aircraft are very cleverly thought out. If one system fails, there’s another that can double for it. You’re taught to be able to fly with most of your gauges out of operation knowing that just a couple of things will guide you to safety. All this has taught me to view the world as a worst case scenario. In fact, a lot of my stories have been born by looking an aspect of the world and thinking of all the ways it can go wrong. I look at a bad idea and turn it into an apocalyptic nightmare.

eries and rigs that prevented noxious chemicals and gases that come up with the crude oil from getting into the atmosphere. That kind of work meant dealing with contingencies. If a valve failed, what was the bypass? If the bypass failed, what was the bypass’ bypass? It was all part of designing to multiple levels of failure. It’s no different than my flying experiences. Aircraft are very cleverly thought out. If one system fails, there’s another that can double for it. You’re taught to be able to fly with most of your gauges out of operation knowing that just a couple of things will guide you to safety. All this has taught me to view the world as a worst case scenario. In fact, a lot of my stories have been born by looking an aspect of the world and thinking of all the ways it can go wrong. I look at a bad idea and turn it into an apocalyptic nightmare.

to defeat the forces arrayed against her. If you want a perfect illustration of this, think of The Hunger Games. Katniss Everdeen is taken from her ordinary world and thrust into a contest to the death, in an arena filled with obstacles and opponents.

to defeat the forces arrayed against her. If you want a perfect illustration of this, think of The Hunger Games. Katniss Everdeen is taken from her ordinary world and thrust into a contest to the death, in an arena filled with obstacles and opponents.