by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Today’s post is for structure fans. If you’re a dedicated pantser for whom any thought of form and function causes you to break out in hives, you have my permission to go play Candy Crush, for we are about to take a deep dive into the skeletal framework of storytelling.

Today’s post is for structure fans. If you’re a dedicated pantser for whom any thought of form and function causes you to break out in hives, you have my permission to go play Candy Crush, for we are about to take a deep dive into the skeletal framework of storytelling.

This post was prompted by an email from a reader of Super Structure and Write Your Novel From the Middle. The gist of the email is below, reproduced with the sender’s permission:

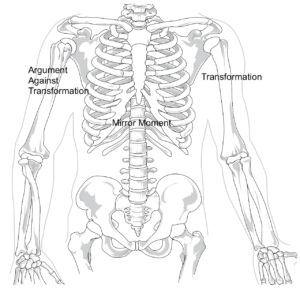

I’m planning a book that is plot-driven rather than character-driven, so as I look at developing my “Mirror Moment,” I know it’s going to be more about digging deep and finding the strength to face physical and/or psychological death (like in The Fugitive), rather than a specific need to change. I wondered how the twin plot points of “Argument Against Transformation” and “Transformation” worked in that case (since there isn’t an actual transformation)? Are those beats skipped in a plot-driven story?

This is a very intelligent question, and told me immediately that my correspondent has a real grasp of structure and what it’s supposed to accomplish.

He rightly points out there are two kinds of arcs for a main character: 1) he becomes a better version of himself; or 2) he remains the same person fundamentally, but grows stronger through the ordeal. (Note: both of these arcs can be reversed, resulting in tragedy).

In books or movies of the first kind, such as Casablanca, you’ll often find a compelling beat, which I call “the argument against transformation.” It’s a setup move which defines the MC’s journey and pays off nicely at the end, with actual transformation.

Thus Rick, at the end of Casablanca, has transformed from a loner who has withdrawn from the community into a self-sacrificing member of the war effort. Remember at the airport, when he’s explaining to Ilsa why they can’t go off together? “I’ve got a job to do, too. Where I’m going, you can’t follow. What I’ve got to do you can’t be any part of.”

Thus Rick, at the end of Casablanca, has transformed from a loner who has withdrawn from the community into a self-sacrificing member of the war effort. Remember at the airport, when he’s explaining to Ilsa why they can’t go off together? “I’ve got a job to do, too. Where I’m going, you can’t follow. What I’ve got to do you can’t be any part of.”

And two minutes later Rick proves his transformation by shooting Major Strasser right in front of Louis, the French police captain.

Early in Act 1, we have Rick’s argument against such a transformation. That is, he states something that is the opposite of what he will come to believe—and be—at the end. He says it two times, in fact: “I stick my neck out for nobody.”

Another example: At the end of The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy has learned, “There’s no place like home.” But early in Act I, she argues against that notion. She tells Toto there’s got to be a place they can go where there’s no trouble, a place you can’t get to by a boat or a train. A place “behind the moon … beyond the rain …” (cue music).

Another example: At the end of The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy has learned, “There’s no place like home.” But early in Act I, she argues against that notion. She tells Toto there’s got to be a place they can go where there’s no trouble, a place you can’t get to by a boat or a train. A place “behind the moon … beyond the rain …” (cue music).

That’s the first kind of transformation. But my correspondent was asking about the second kind, where the character does not change inside. Here’s what I wrote in response:

In the kind of story you describe, there is a transformation—from weaker to stronger. The hero is forced to survive in the dark world, and must become more resilient. So at the end he is not fundamentally a different person, but is a stronger, more resourceful version of himself.

In thinking about your question, it seems to me that the “argument against transformation” in a “getting stronger” story corresponds to what my friend Chris Vogler labels “Refusal of the Call” (in his book The Writer’s Journey). One example Chris uses is Rocky. When Rocky Balboa is first offered the chance to fight Apollo Creed, he says no. “Well, it’s just that, you see, uh…I fight in clubs, you know. I’m a ham-and-egger. This guy… he’s the best, and, uh, it wouldn’t be such a good fight. But thank you very much, you know.”

Implicit in that refusal is his belief that he’s not strong enough.

The transformation beat comes at the conclusion of the final battle, usually in the form of some visual that shows the stronger self. In Rocky, he’s got Adrian in his arms and adulation from the fans.

In The Fugitive, the argument against transformation is shown cinematically. After Sam Gerard (Tommy Lee Jones) arrives on the scene of the train derailment, we cut to Kimble running through the woods, his face etched with fear. In a book, you could put in Kimble’s inner thoughts about it. I know an operating chamber, not the streets! How am I going to survive?

The Mirror Moment is what holds these two ends of the spectrum together, which is why it is perfectly situated in the middle of a book. The protagonist has a moment when he’s forced to look at his situation, as if in a mirror (sometimes there’s an actual mirror in the scene!). He either thinks, Who am I? What have I become? Will I stay this way? (Casablanca); or, There is no possible way I can survive this…I’m probably going to die! (The Fugitive).

Now, if you pantsers have made it this far without your heads exploding, I congratulate you, and offer this word of comfort: you don’t have to think about structure before you start a project, or while you’re writing it. Go ahead, be as wild and free as you like!

But when the time comes (and it always does) when you need to revise and figure out why something isn’t working—and what you can do to make it work—structure will be there to help you figure it out.

Because story and structure are in love, and there’s no argument against that!

***

Gilstrap Watch: John reports that the surgery “went great.” He feels, naturally, like he “took a beating,” but expects to be “fine in a week or two.” Huzzah! (For those who don’t know what this is about, see John’s post from last Wednesday.)

to defeat the forces arrayed against her. If you want a perfect illustration of this, think of The Hunger Games. Katniss Everdeen is taken from her ordinary world and thrust into a contest to the death, in an arena filled with obstacles and opponents.

to defeat the forces arrayed against her. If you want a perfect illustration of this, think of The Hunger Games. Katniss Everdeen is taken from her ordinary world and thrust into a contest to the death, in an arena filled with obstacles and opponents.