by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Today’s post is for structure fans. If you’re a dedicated pantser for whom any thought of form and function causes you to break out in hives, you have my permission to go play Candy Crush, for we are about to take a deep dive into the skeletal framework of storytelling.

Today’s post is for structure fans. If you’re a dedicated pantser for whom any thought of form and function causes you to break out in hives, you have my permission to go play Candy Crush, for we are about to take a deep dive into the skeletal framework of storytelling.

This post was prompted by an email from a reader of Super Structure and Write Your Novel From the Middle. The gist of the email is below, reproduced with the sender’s permission:

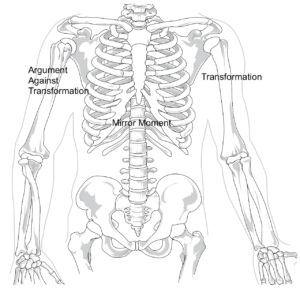

I’m planning a book that is plot-driven rather than character-driven, so as I look at developing my “Mirror Moment,” I know it’s going to be more about digging deep and finding the strength to face physical and/or psychological death (like in The Fugitive), rather than a specific need to change. I wondered how the twin plot points of “Argument Against Transformation” and “Transformation” worked in that case (since there isn’t an actual transformation)? Are those beats skipped in a plot-driven story?

This is a very intelligent question, and told me immediately that my correspondent has a real grasp of structure and what it’s supposed to accomplish.

He rightly points out there are two kinds of arcs for a main character: 1) he becomes a better version of himself; or 2) he remains the same person fundamentally, but grows stronger through the ordeal. (Note: both of these arcs can be reversed, resulting in tragedy).

In books or movies of the first kind, such as Casablanca, you’ll often find a compelling beat, which I call “the argument against transformation.” It’s a setup move which defines the MC’s journey and pays off nicely at the end, with actual transformation.

Thus Rick, at the end of Casablanca, has transformed from a loner who has withdrawn from the community into a self-sacrificing member of the war effort. Remember at the airport, when he’s explaining to Ilsa why they can’t go off together? “I’ve got a job to do, too. Where I’m going, you can’t follow. What I’ve got to do you can’t be any part of.”

Thus Rick, at the end of Casablanca, has transformed from a loner who has withdrawn from the community into a self-sacrificing member of the war effort. Remember at the airport, when he’s explaining to Ilsa why they can’t go off together? “I’ve got a job to do, too. Where I’m going, you can’t follow. What I’ve got to do you can’t be any part of.”

And two minutes later Rick proves his transformation by shooting Major Strasser right in front of Louis, the French police captain.

Early in Act 1, we have Rick’s argument against such a transformation. That is, he states something that is the opposite of what he will come to believe—and be—at the end. He says it two times, in fact: “I stick my neck out for nobody.”

Another example: At the end of The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy has learned, “There’s no place like home.” But early in Act I, she argues against that notion. She tells Toto there’s got to be a place they can go where there’s no trouble, a place you can’t get to by a boat or a train. A place “behind the moon … beyond the rain …” (cue music).

Another example: At the end of The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy has learned, “There’s no place like home.” But early in Act I, she argues against that notion. She tells Toto there’s got to be a place they can go where there’s no trouble, a place you can’t get to by a boat or a train. A place “behind the moon … beyond the rain …” (cue music).

That’s the first kind of transformation. But my correspondent was asking about the second kind, where the character does not change inside. Here’s what I wrote in response:

In the kind of story you describe, there is a transformation—from weaker to stronger. The hero is forced to survive in the dark world, and must become more resilient. So at the end he is not fundamentally a different person, but is a stronger, more resourceful version of himself.

In thinking about your question, it seems to me that the “argument against transformation” in a “getting stronger” story corresponds to what my friend Chris Vogler labels “Refusal of the Call” (in his book The Writer’s Journey). One example Chris uses is Rocky. When Rocky Balboa is first offered the chance to fight Apollo Creed, he says no. “Well, it’s just that, you see, uh…I fight in clubs, you know. I’m a ham-and-egger. This guy… he’s the best, and, uh, it wouldn’t be such a good fight. But thank you very much, you know.”

Implicit in that refusal is his belief that he’s not strong enough.

The transformation beat comes at the conclusion of the final battle, usually in the form of some visual that shows the stronger self. In Rocky, he’s got Adrian in his arms and adulation from the fans.

In The Fugitive, the argument against transformation is shown cinematically. After Sam Gerard (Tommy Lee Jones) arrives on the scene of the train derailment, we cut to Kimble running through the woods, his face etched with fear. In a book, you could put in Kimble’s inner thoughts about it. I know an operating chamber, not the streets! How am I going to survive?

The Mirror Moment is what holds these two ends of the spectrum together, which is why it is perfectly situated in the middle of a book. The protagonist has a moment when he’s forced to look at his situation, as if in a mirror (sometimes there’s an actual mirror in the scene!). He either thinks, Who am I? What have I become? Will I stay this way? (Casablanca); or, There is no possible way I can survive this…I’m probably going to die! (The Fugitive).

Now, if you pantsers have made it this far without your heads exploding, I congratulate you, and offer this word of comfort: you don’t have to think about structure before you start a project, or while you’re writing it. Go ahead, be as wild and free as you like!

But when the time comes (and it always does) when you need to revise and figure out why something isn’t working—and what you can do to make it work—structure will be there to help you figure it out.

Because story and structure are in love, and there’s no argument against that!

***

Gilstrap Watch: John reports that the surgery “went great.” He feels, naturally, like he “took a beating,” but expects to be “fine in a week or two.” Huzzah! (For those who don’t know what this is about, see John’s post from last Wednesday.)

Hi Jim,

My apology in advance for the lengthy comment to come.

As a dedicated practitioner of writing off into the unknown — and thereby being only the first of hundreds of readers who are entertained when my characters tell their own story — let me be the first “pantser” to say I agree that Structure is important.

However, I learn and absorb Structure (from you et al and from reading fiction extensively) with my conscious, critical mind. Just as I learned sentence structure (and the use of fragments) and the appropriate use punctuation or to always dot the lower-case I or to always cross a T when writing.

I don’t “think” about structure as I write anymore than I “think” about whether to dot an I or cross a T or whether the end of a sentence needs a period or a question mark.

Once I take it on board (i.e., learn it) a given technique (including structure) becomes automatic and seeps through my fingers and into the story as I write.

I simply prefer not to force my authorial will on my characters’ story as they live their lives, anymore than I would attempt to force my will on my neighbors as they live their lives.

Of course, every writer is different.

I personally can’t bring myself to outline a novel before I write it because if I already knew every plot twist, character trait, etc. I would be bored to tears as I wrote. It would be like trying to watch and enjoy a film when I already knew the ending or trying to watch and enjoy a baseball game after someone had already told me the score.

My characters entertain me as they race through the story. I am the fortunate Recorder they’ve invited to drop into the story with them. I attempt to keep up as I record what they say and do, enter and extract themselves from various situations, solve crimes, battle aliens, solve murders or ride wild on a good horse in a noble endeavor.

I’m thrilled that I don’t know what’s coming next.

And revision? Yes. I run a spell checker and I have a first reader who checks for any typos or inconsistencies. I generally spend all of a half-hour applying those fixes (if I agree with them) before allowing my toddling little novel out the door.

But beyond that, I personally prefer not to polish my original voice off the story with endless revisions and rewrites. I prefer instead to write a story cleanly the first time through, publish it and move on to the next story.

Nothing about my personal writing process should seem threatening-to or evoke derogatory or condescending terms (“pantser”) from those who have a different process (outlining, revising, rewriting, polishing, etc.). Are these folks “plodders”? Maybe. I just don’t care.

After all, my process has no bearing on others’ processes (or theirs on mine), and neither does my success as a novelist have any bearing on others’ success or lack thereof.

Respectfully (in case there was any doubt),

Harvey

Say, Harvey, I don’t consider “pantser” a derogatory term. It’s been in use for some time now, and if you can land the plane (which is where “seat of the pants” came from), terrific. The plane may still need some fixing…and if you’ve landed in a lost jungle somewhere, structure can be a map to help you find your way out!

I’m with you, Harvey. I believe in structure and planning, but only to a point. I don’t outline (it would bore me to tears as well) but I “template” out about four chapters at a time. I never know the end until it is in my headlights. But as things change and serendipity intrudes, I rewrite (sometimes as I go along, sometimes at the end, usually both.)

Writing, for me, is akin to the saying “Life is what happens to you when you’re making other plans. ” Yeah, stay on a path but always be open to the beautiful detour.

* I always thought it was John Lennon who came up with this line in his song “Beautiful Boy.” Turns out it appeared in Earl Wilson’s column back in 1958!

Now, if you pantsers have made it this far without your heads exploding, I congratulate you, and offer this word of comfort: you don’t have to think about structure before you start a project, or while you’re writing it. Go ahead, be as wild and free as you like!

But when the time comes (and it always does) when you need to revise and figure out why something isn’t working—and what you can do to make it work—structure will be there to help you figure it out.

As a planster, thinking about structure before I write stifles the output. I recently took a workshop of character building from Stant Litore, and he added “You need Character Arc scenes” which added another layer of “can’t do this” to my writing. But my process is to write the damn book first, with minor fixes along the way, and once I get my fingers on the keyboard and start writing, I have something to fix in rewrites. Litore talked about the characters’ “inner wounds” and I’ve been thinking about that as my hero and heroine are going through the “push-pull” of their building relationship.

I’m still a GMC kind of writer.

And thanks for the update on John Gilstrap. I’m recapping his workshop on writing suspense over at my blog.

In Super Structure I write about “signpost scene writing.” Instead of an outline, you can at least point to the next signpost, not even knowing what’s coming after that. When you reach that point, brainstorm another signpost. It’s still “discovery writing” and every bit as fun, with the added benefit of creating a skeleton that can dance.

I discovered this quote from E. L. Doctorow when I was starting out, and that’s been my approach ever since. “It’s like driving a car at night. You never see further than your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.”

The exact quote I use in my book. I always liked it. Only as a thriller writer I’ve discovered it’s best (for me) to know the destination. That way I can drop red herrings and mysteries on the pavement.

I go back and litter afterward.

I quote that one often in workshops. 🙂

My argument for being a planner is that I come up with ideas way faster than I can write. My mind is whirling 24/7, and I’m only toiling at the keyboard for about an hour a day, and working on finishing an old story. Stopping myself from daydreaming cripples my creativity way more than knowing what comes next when I write. I guess I pantse when I dream, because the stuff I come up with never feels forced or cliched.

Someday I’ll read Superstructure. Someday the website that produces electronic braille books will give me my requested book. Until then, thanks for the post.

Bradbury had a quote about getting up in the morning and exploding, then spending the rest of the day putting together the pieces. This assumes you know how to distinguish a pattern.

Thanks for another great post.

What struck me, after reading your post and the responses, is that there are an infinite number of possibilities on the spectrum between writing with an outline (or skeleton) and writing with no pre-planning at all. And every one of those “infinite” points seems to be inhabited by a writer and “their” approach. Some have every last detail outlined and planned. Some, like Harvey, have learned and internalized the structure the final product must possess to be satisfying and successful, and need absolutely no pre-planning.

Personally, I consider myself a beginner, and I’m soaking up all the teaching on structure that I can find. All of your books have been extremely helpful. I’ve read them and reread them.

My approach is gradually changing, as I internalize the laws of physics (Larry Brook’s term) as to what must happen for a successful outcome. Currently, I brainstorm and write down everything in no particular order, then organize according to Superstructure and “sign posts,” then see what else I need to be digging out of the creative basement. At that point, I take off and enjoy the journey. At the end, comes the editing and repairs.

Infinite choices, but the final product must have structure to succeed.

Steve, your latest approach is similar to mine. One of my favorite things to do before the writing is to sit down with coffee and a stack of 3×5 cards and just brainstorm scenes. Let the boys in the basement roam free. Later, I’ll shuffle this deck and look for interesting connections. Eventually, the best scenes go into the structural outline.

Neither pantser nor outliner, I’m a hybrid. Having struggled with structure and the “journey” steps for years, I found my writing comfort in both of your books, Jim. The thing is, the three-act construct and its components are now a subconscious tool as I watch my characters develop the story, including those surprises Harvey loves so well. Sometimes a character’s spontaneous response to conflict will take me down a new, unforeseen path, but I always find a way to stick to the signposts I set out earlier. I discovered I really need those signposts.

Quite often I write the ending chapter(s) early or first. Doing so helps me mold the plot as things evolve. The Mirror Moment was a real eye opener to me as a fulcrum for the main character arc. Keeping structure in mind is no longer forced, nor is the Mirror Moment, although exact placement sometimes eludes me.

Every storyteller eventually faces the skeletal makeup of a good plot. These two books simply made applying it more instinctual for me.

Dan, a hearty agreement with all you said.

The thing is, the three-act construct and its components are now a subconscious tool as I watch my characters develop the story

I often analogize writing to golf. When you play, play! Don’t think about the ten components of a good swing, etc. You do that after you play and when you practice. The idea is to get it all into “muscle memory.” That’s what a grip on structure is like.

Lee Child likes to say he doesn’t outline and indeed often doesn’t know what’s coming in the next chapter. But his background in TV put all that in his head. He’s doing signposts subconsciously.

I like JSB’s signpost method. And Larry Brooks’ physics. But I go even further: I’m a “Covter.” Once I have a concept and then a premise, I next design a draft of the book’s cover. I want to *see* the finished book in front of me before I start writing. These cover drafts invariably change as I work through the story, but they provide me with a visual reminder of what I’m working toward.

I love that idea, Harald. I do a mock cover before I do my first read-through of a draft,, even putting a blurb that says what a great writer I am (according to the New York Herald Tribune). I want to have the feeling of reading a book by an author I admire. Ha!

The NY Trib… good one!

Well, I was featured in the New York Post and the (New York) Daily News, but that was for *swimming around* Manhattan, not writing about it. Does that count?

It looks like I’m in the minority here, but I love structure. By planning at least the milestones, I always know where I’m going next. That’s not to say the original plan can’t veer off course if a better idea comes along while writing, but I do enjoy not having to stare at a blank page and wonder what to write. I’m either setting up a future scene or paying it off. Structure allows me the freedom to twist plot threads with the ultimate goal of leading the reader back to the main road, so to speak, and end up with a solid first draft.

Thanks for the update on John. Please send him my best.

Structure allows me the freedom to twist plot threads with the ultimate goal of leading the reader back to the main road, so to speak, and end up with a solid first draft.

Exactly, Sue. Well said! Many writers see structure as confining, but it’s actually just a different kind of freedom. It’s not hedonism, it’s teleology, as Aristotle might have put it if he ever tried to write a screenplay.

100%

Working with newer writers, I’ve seen the problem with both extremes in writing method. People who just write with no plan more often than outliners end up with a book that can’t be finished or a what-the-hell story that confuses or leaves false trails. They also have trouble hitting the right word limit for the type of book they are writing. (Children, back in ancient times when writers sold to traditional publishers instead of self-publishing, they had to write a very specific length.)

The outliner can be so obsessed with the outline that she silences the voices of her characters and her subconscious who are telling her there’s a better way to continue.

I’m more of a fan of a mixture of the two types of plotting. I choose my major plot points ahead of time, the major character arcs, and figure out the general structure of the subplots, then I let my imagination fill the rest as I write.

Back to the discussion about what your article is really about, James, the lack of transformation story works best in a series, particularly certain types of mysteries like procedurals and detective stories. Also, some fantasies and adventures that are action based. No transformation would be a disaster in a romance or some other emotionally intimate novel because they are all about change.

Asimov said he knew his beginning and his end, then “had the fun” of filling up the in between. He did okay…

“… it’s teleology, as Aristotle might have put it if he ever tried to write a screenplay.” I had to look that one up. Dictionary.com defines it as “The belief that purpose and design are a part of or are apparent in nature.” I’m with Aristotle on this one.

I wonder if there’s a place for the experimentalist in creative writing. I was definitely a pantser when writing the first draft of my first novel. But then I realized I hadn’t stated the underlying purpose very well, so I got a copy of “Plot & Structure” and spent a lot of time learning and rewriting. It’s was exciting to see it come together.

Now I’m working on novel #2 and I’m taking a different course of action. I’m using Scrivener to outline scenes and plan to have the entire story plotted at a very high level before I commit to adding a lot of detail. After reading “Write Your Novel from the Middle,” I came up with a “mirror moment” where the MC has to decide if she’s willing to put her own life at risk to save a friend.

My point here is that I’m not sure I’ll ever settle down into one methodology. How many novels do you have to write before finding your place on the spectrum?

I’ve written 13 novels–6 are in print, 3 could be in print, 4 are outdated or disasters. My answer is you never find the perfect methodology. You change, some novels demand different methods, and narrative market demands change. What you do find, however, is a confidence that you can trust yourself with the method you choose for a particular novel.

Exactly why I love Scrivener, Kay. It’s so flexible and useful for any type of writer.

I like your current “method,” because, well, it “mirrors” my own. But certainly you can experiment. I still do. A few weeks ago I mentioned writing a really fast first draft by skipping over transitions. I’m giving that a whirl right now. I love finding new ways to work.

Pingback: Using the Argument Against Transformation to Strengthen Your Story | Loleta Abi

Pantser here, too. Don’t like the term much either, but it’s what it is.

The problem is that no one teaches structure for pantsers. Instead, we’re told to do plot points and other outlining techniques. I struggled with structure for many years and never felt like anyone understood how I wrote. I went the structure route, followed the usual advice (three act, plot points, etc)–I even outlined. And watched a perfectly good story turn into a minor two car accident and then into a twenty car pileup and then into a spaceship that crashed and took out an entire city. At one point, someone offered to read it to help me with my problems, and I was ashamed to show it to her. I was so much of a better writer than what I had tortuously produced.

I went all over the place, trying to find answers…and all I got from other writers was that I wasn’t outlining correctly. Not one person said, “Maybe you shouldn’t use an outline.”

I was very fortunate to have found a structure and secondary plots workshop that showed me how to do it from the pantser perspective. I learned an incredible amount…and you know, I still don’t outline. I’m doing a mystery. I have no idea who did it or how it’s going to end. I’m writing a SF novel and have the first chapter. I don’t even know what’s going to be in the second chapter. And it’s great fun doing it like that.

The problem is that no one teaches structure for pantsers. Instead, we’re told to do plot points and other outlining techniques.

This drives me a little nuts. *I* teach structure for pantsers…and everyone else. The issue is not outlining! You don’t have to outline before you write. You do have to structure after.you write. So knowing what structure is and does comes in mighty handy.

But you outline normally when you write, don’t you? One of the things I’ve observed is that there is a difference to the advice when it comes from someone who outlines as a default, because the frame of reference is so different. I don’t think a lot of writers even realize it. I sure didn’t until I ran into two professional writers who didn’t outline who gave craft advice. The differences were very subtle, but they were differences that directly impacted how I wrote.

While some people can add structure into the second draft, if it’s not in my first, the story is broken. It cannot be fixed because there are too many connected parts (it would take 20 drafts. Each change would break something else, and fixing that in turn break more things–and it would never be right). That means I do it as I pants the story, but as far as I can tell, it’s not the same experience everyone else talks about.

That means I do it as I pants the story,

If by “it” you mean structure and “connecting the parts,” then it helps to know structure, yes? What you’re discovering is the story within the structure, as you move along. Perfectly fine. The signposts can help you make your moves.

John Braine’s method was write a first draft as fast as you can, then step back and look at what you have, then create an outline which might, indeed, change many of the “connecting parts.” Then write the whole thing again. I’ve never tried that one, though it worked for him.

Which is the point. What works for the writer? But also knowing that, ultimately, it has to work for the reader or it’s all just typing practice.