by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

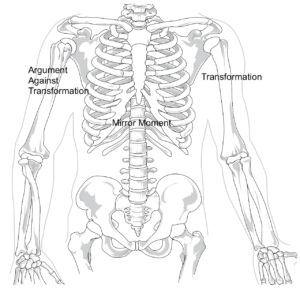

In Write Your Novel From the Middle, I explain a crucial moment in a plot where the lead character must make a choice. It usually involves a moral dilemma, with the character’s realization of who he is and how his flaws affect the characters around him. He then has to make a decision about what kind of person he is going to be: Stay the same and continue to hurt people? Or find his way to redemption?

In the middle of Casablanca, for example, we see Rick being a mean drunk toward Ilsa, who has just poured her heart out to him explaining why she had to leave him in Paris. As soon as she tearfully exits the scene, Rick drops his head into his hands, and we know he’s looking with disgust at himself, as if in a mirror. That’s why I call this the “mirror moment” which usually happens smack dab in the middle of a novel or film. Indeed, it is the moment that tells us what the story is really all about.

Casablanca does something else to magnify Rick’s dilemma—it places Rick between two characters who represent opposite moral poles. On one side is Louis Renault, the corrupt French police captain whose sole purpose in life is holding on to his cushy job and bedding desperate women trying to get out of Casablanca. He isn’t loyal to the French or the Germans; he’s loyal to Louis, and does what he can to keep from rocking the boat.

On the other side of Rick is Victor Laszlo, the heroic resistance fighter. Rick admires him, but isn’t going to help him, even though Louis has announced his impending arrest in Rick’s café. In addition to his avowed detachment, Rick has another reason not to help Laszlo—turns out he’s married to Ilsa, the woman Rick believes betrayed him.

What Casablanca is really about, then, is how Rick gets to the decision not just to help Laszlo and Ilsa, but even to sacrifice his life (potentially) to do it. And in the famous ending twist, Rick’s moral reformation inspires Louis to make a similar choice. It’s “the beginning of a beautiful friendship.”

Hold that thought.

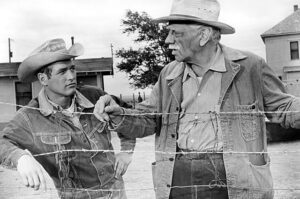

The other night I watched the Paul Newman film, Hud (1963). This superb movie (based on Larry McMurtry’s novel Horseman, Pass By) won three well-deserved Academy Awards: Best Actress (Patricia Neal); Best Supporting Actor (Melvyn Douglas); and Best Cinematography (James Wong Howe). The protagonist is Lon Bannon. He lives on a modest cattle ranch with his Granddad and uncle, Hud, and Alma, their housekeeper.

Lon has just turned seventeen. He’s on the cusp of adulthood. And he’s offered two paths. The first is from his beloved Granddad, who has built his entire life on working hard and doing what’s right and honest. The other is from Hud, whom Lon admires for his way with women and ease at being a “good ol’ boy.” As Hud explains to Lon, “When I was your age, I couldn’t get enough of anything.” Lon is increasingly leaning in Hud’s direction.

Then tragedy strikes the ranch. A herd of cattle Granddad recently brought in from Mexico has foot-and-mouth disease. All of the cows have to socially distance be exterminated. Hud tries to convince his father to sell off the bad cows to unsuspecting neighbors. Granddad, of course, will have none of it. “You’re an unprincipled man, Hud,” he says.

“Don’t let that fuss you,” Hud snaps back. “You’ve got enough for both of us.” Indeed, deep down, Hud would like nothing better than for Granddad to kick the bucket so Hud can take his half of the ranch and do what he pleases with it.

Once again, the mirror moment happens in the middle of the film. Lon and Granddad have gone to a movie together and are having a bite to eat at a diner. Hud comes stumbling in with a woman—another man’s wife. There’s a tense exchange between Hud and Granddad, who clasps his chest and keels over. Hud and Lon get him into a pickup truck and drive him back to the ranch. As Granddad sleeps between them, Lon says:

LON: He’s beginning to look kind of worn out, isn’t he? Sometimes I forget how old he is. Guess I just don’t want to think about it.

HUD: It’s time you started.

LON: I know he’s gonna die someday. I know that much.

HUD: He is.

LON: Makes me feel like somebody dumped me into a cold river.

HUD: Happens to everybody. Horses, dogs, men. Nobody gets out of life alive.

That “dumped into a cold river” is Lon’s awakening to the stakes. He’s going to have to make a decision on how to live life once Granddad is gone.

Two plot points happen that turn Lon away from Hud. First is Hud’s attempted rape of Alma, which Lon breaks up. Alma has been through the grinder of life, and Lon considers her good and kind. Seeing what Hud tries to do to her disgusts him.

The second point is when Lon and Hud are driving back to the ranch from a carouse in town and find Garnddad crawling on the road. He’d fallen off his horse, and is in bad shape. Lon cradles his head, tells him to hang on, that everything will be all right. Granddad says, “I don’t know if I want it to be.” He looks over at Hud. “Hud’s here waitin’ on me. And he ain’t a patient man.” With that he gives up the ghost.

Hud’s ill treatment of Granddad is the final straw for Lon. He decides to pack up and leave, not quite sure where he’ll end up. Hud makes one last pitch for Lon to stay on.

HUD: I guess you’ve come to be of your granddaddy’s opinion that I ain’t fit to live with. That’s too bad. We might’ve whooped it up some. That’s the way you used to want it.

LON: I used to. So long, Hud.

Lon walks away. Hud goes into the ranch house and grabs a beer from the icebox. He returns to the door to look at his departing nephew. Then, with a dismissive wave, he shuts the door.

That’s the end. Hud is all alone. No one to love him, no one for him to love. In this instance, contrary to Casablanca, the immoral character does not change, and we are shown the tragedy of that choice.

So consider setting your Lead between two characters who represent opposites on the moral scale. This will deepen the Lead’s dilemma and the story as a whole.

Comments welcome.